Like the island from which it got its name, the story of Oranda-jima House in the Japanese town of Yamada-machi has its beginnings in a tragic disaster. Oranda-jima (meaning “Holland island”) in the Bay of Yamada is where, in 1643, a Dutch ship called Breskens ran aground. The ship’s crew was without supplies but the locals came to their aid with food, drink and hospitality.

It was an act of assistance that was recalled after the trauma of the earthquake and tsunami that struck in March 2011. A group of Dutch business people living in Japan wanted to do something to help.

“We thought that it would be a good opportunity to return the favour, although it was 368 years later,” says architect Martin van der Linden of the Tokyo-based firm Van der Architects.

“Having gone to Yamada-machi shortly after the tsunami and seeing the devastation first hand was our biggest inspiration and motivation,” he says. So they proposed building an after-care facility for the town’s children, who were dealing with the trauma of having lost relatives, friends and neighbours.

One thing that we learned from having lived in Japan over a long period of time is that it lacks mental care, says Van der Linden, who has lived in Tokyo since the end of 1995.

Oranda-jima House reently won a Silver A' Design Award in the Architecture, Building and Structure Design Category. In designing the building, Van der Linden consulted with a Japanese psychiatrist in creating a therapeutic environment that would encourage play and help the children to feel calm and safe.

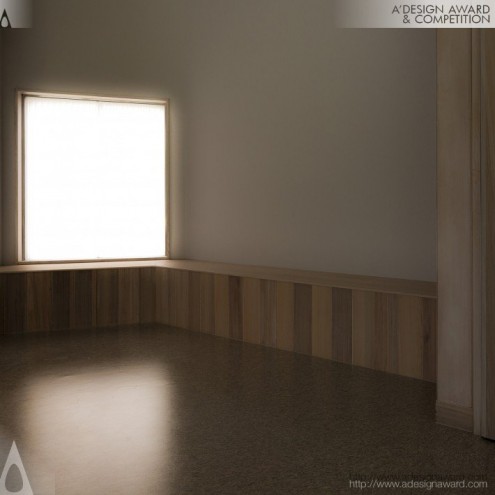

The building, which opened in May 2014, is positioned to maximise the movement of light during the day and from season to season. Daylight floods the space from 3 pm to 7 pm when the building is in use by the children. During the winter months light penetrates deep into its interior, while an overhang provides shade in summer.

Some of the rooms, such as the library, have a lowered ceiling with no windows except for a toplight. The idea was to create a calming space that made the children feel contained, explains Van der Linden. As the light slowly changes during the day it softly touches the rough stucco wall of the room, accentuating its texture.

Van der Linden’s design is mindful of the small moments – something he hopes will have a subtle impact on the children. Take, for example, a translucent polycarbonate window on the building’s west side. Behind this window are trees and the orange light of dusk will cast beautiful shadows on this panel, not unlike patterns seen in Japanese rice paper screens. During autumn and winter when the sun sets low, the room will glow a deep orange for a few minutes when the sun’s rays filter through the window.

The low-slung building is made of wood and clad in timber – a decision made in order to involve local industry in the construction.

Building out of wood made it possible to construct the building 100% by local carpenters, says the architect.

Somewhat unusually for a children’s space, the interior is deliberately neutral in colour to encourage calm rather than noise.

All in all, it’s a soothing and secure refuge that nonetheless embraces its environment. “The way the light travels through the building and changes the lighting during [the afternoon] hours creates a quiet, theatrical play that consciously or unconsciously has an effect on the children's wellbeing.”