Architect Ilze Wolff has a knack for turning setbacks into opportunities. Take these two instances:

The first happened while she was still a student of architecture at UCT (University of Cape Town). She wanted to study a particular building in Cape Town’s Salt River, but her lecturers didn't think the building was significant enough. In fact, when she first prepared her research outline to study the Rex Trueform building, her lecturers in the architectural department failed the proposal.

Rex Trueform sits at the corner of Queenspark Avenue and Victoria Road, and it used to be a clothing factory that employed mostly people of colour during apartheid, including some of Ilze’s relatives.

The modernist building by architect Max Policansky was completed in 1937 and although the apartheid government would not start segregating the population until a few years later in 1948, this one had separate bathroom amenities.

Coloured people who made up most of the staff on the factory floor had their own separate entrance to that of admin staff, which mostly consisted of white people. Says Ilze: “If you look at it, the duplication of space is very expensive. and you think for people that were so focused on making money, why would they spend all this money to duplicate these things?”

Questions like this and more, including the role of the city’s built heritage in racial segregation, led her research to the African Studies department after she was rejected by her architecture lecturers. She not only finished the course with distinction, but went on to publish her research in a book that was launched in Rome last month.

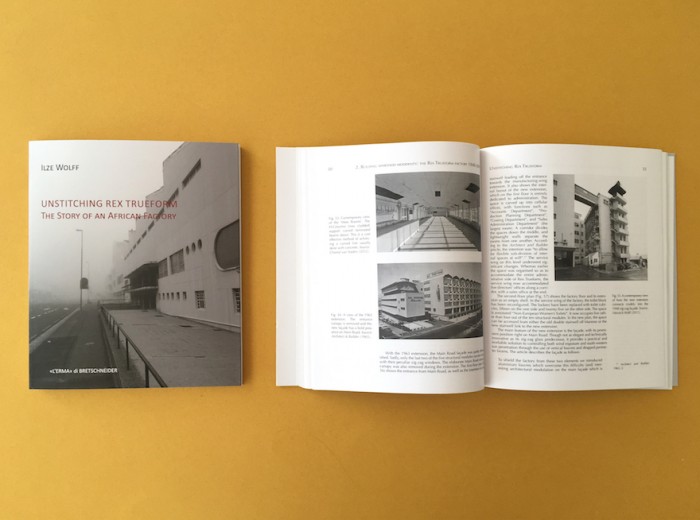

The book called ‘Unstitching Rex Trueform: the story of an African factory’ is published by L’erma Di Bretschneider and has received the International Prize for Scholarly Works in Modern and Contemporary Art and Architecture.

The book tracks the life of the clothing factory and how this modern architecture is entangled in our readings of race, gender and society. It also asks bold questions about the current rapid changes of industrial neighbourhoods in Cape Town, exploring how to be sensitive to past injustices of forced removals, labour and gentrification in the city.

In another incident, Wolff Architects, which Ilze runs with her husband Heinrich, recently found out that the Department of Arts and Culture had decided not to award any tenders for the South African Pavilion at the Architecture Biennale in Venice this year.

This is despite the fact that there was a tender submission process for it last year. This news means that the pavilion, the maintenance of which is paid for by South African taxpayers, would be standing empty this year.

The architects decided to take their dissatisfaction with the decision and instead host an exhibition at their Cape Town offices.

The exhibition, which will take place a few days before the opening of the Venice event in May, will be based on the proposal they had sent to the department.

Now an open call for local artist to exhibit, it invites photographers to submit an image of an oppressive space, psychologically or spatially. These images will then be printed small, the size of an Instagram thumbnail.

Then upon entering the space it would appear that there is nothing on the walls except a specially chosen image that would ask the audience to imagine alternatives.

With the exhibition Wolff wants to probe if these images could stimulate urgent discussions around the state of contemporary architecture.

This would not be the first time the architects host an exhibition in their Bo-Kaap office. Ilze explains that they collaborate with artists, theatre-makers, photographers but also make the space available for public meetings and events.

Ilze and Heinrich have been operating in the building for years, turning the bottom part of the building into a semi-public space while the rest of the practice works upstairs. The architects, whose projects include the Chere Botha School (above) and Watershed at the V&A Waterfront (below), say it is important for them to offer this kind of space in an area like Bo Kaap because not many spaces like this exist in the Cape Town CBD.

“It’s kind of like our threshold between practice and the public. We try very hard to develop public culture around architecture. It's very important for us to have programs in the office that has exhibitions and talks. We've got a team that’s specifically looks at that in the office,” says Ilze who was recently shortlisted for the Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture at Architectural Review’s Women in Architecture Awards.

This builds on the architects’ earlier work with Open House Architecture where they’d give tours of significant Cape Town buildings to architects, students and the general public.

“I realised there was a real need to have a conversation about architecture, space and heritage as well as how we take the idea of making that public culture the conversation together with the practice,” Ilze says.

But while the architects prepare for exhibition in their office in May, they have also been working on another exhibition, this time in collaboration with architect and curator Mpho Matsipa.

The exhibition is currently taking place until 19 August at one of the biggest spaces for architecture in Europe, the Pinakotek de Moderne in Munich. Called “African Mobilities: This is not a refugee camp exhibition”, the architects were invited to design the space which consists of three big rooms in which to explore mapping, new technology and thinking around new futures.

“The figure of the refugee is quite a common figure in the imagination of Europe, so how do you think about that differently when you’re thinking about Africa?” Ilze says.

Ilze says since July last year, the curator, Matsipa invited different artists from all over the continent. They have been having various exchanges as part of the project that will result in work that is to be exhibited in the space.

There will also be a sound booth where headphones will be hung around for people to explore audio files.

Ilze adds that the exhibition worked to bring in the whole Pan African experience and an example of this is a map of Manhattan, illustrating the immobility of black people, a project by Global Africa Lab.

This part of the exhibition will be a meditation on Black Lives Matter, in this way, the idea of borders and crossings in not only linked to ones within the continent but rather a Pan African experience.

“Which then brings me to the heart of this exhibition, which is the Chimurenga Library. They are one of the big commissions in this space, where they have asked each and every participant (whether you're a curator or a designer) to produce or offer 10 books, vinyls, films that could go into a library that remaps this idea of African mobilities,” she says.

The Cape Town-based Chimurenga Library has asked the museum to source these items from the participants in order to have them in the space during the exhibition as a kind of a space of delay, contemplation and reflection.

“One of the aspects that we really wanted to do with this design was to allow people to just sit and go through the material and think. not like a normal exhibition where you’re just going through this thing, taking in as much as you can then going home. So, this space is hopefully where people will interact with the materials, with the books, with the vinyls, with the audio files and the poster files. We designed the pop-up library for Chimurenga,” she adds.

“We provided many blank spaces, we provided a generous hang out space to read, listen and to look out of the window. We provided equal amounts of light and shadow. We composed a space that is layered with geometry, tactile materials and easy movement for the viewers. The geometries that we chose playfully distort the gallery space whilst making immersive and compelling spaces for viewing, listening, interpreting, socialising and browsing.”

Read More:

Somali Architecture students are stitching back the country's built heritage digitally

Cairo architect Nada Elhadedy on architecture driven by circumstance

Aiming for Democratic Architecture exhibition taps into the role of architecture in democracy