The more we move – around the world, from job to job, between rented apartments and from one phase of life to the next – the more our cities change, says Teresa Palmieri. The desginer from the small town of Trento in northern Italy believes this constant “in-between” motion has given rise to a new kind of social character: the “settled-nomad”.

Her final project for her Master’s degree in social design at Design Academy Eindhoven, titled “Settled-nomads in search of temporary stability”, researched the ways we inhabit the world today.

“The population of cities becomes multiform: immigrants and migrants, commuters, people who move for work and study reasons,” Palmieri says. “They mark the territory in a way that we can no longer ignore.”

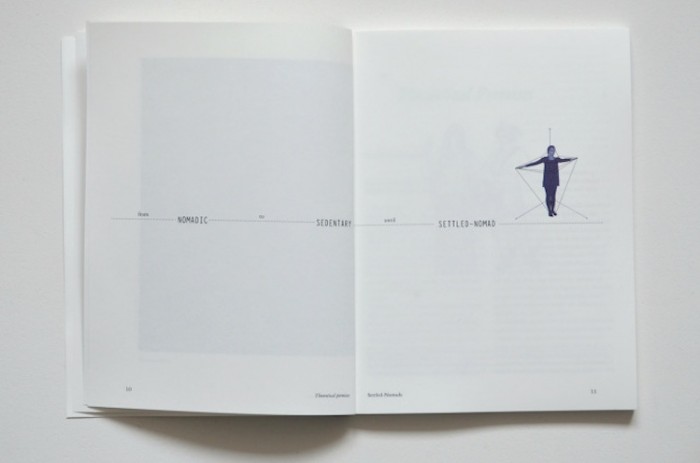

In this context nomadic and sedentary life are no longer distinguishable.

“A lot of people live their life marked in equal ways by permanence and mobility,” she says.

Her project analyses mobile living and questions how this lifestyle influences the way in which people experience and perform a sense of belonging in relation to a place that they are inhabiting temporarily.

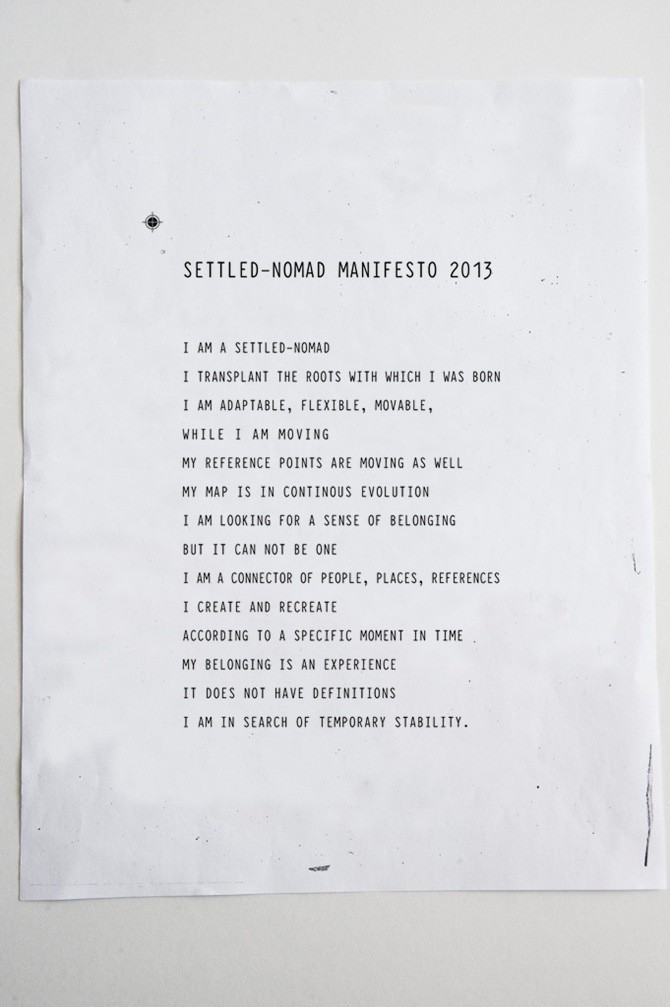

She describes the settled-nomad as “a hybrid person, partly sedentary and partly nomadic, who perfectly embodies the spirit of our time”.

The settled-nomad must constantly adapt to his changing environment. His sense of belonging is not a given and doesn’t emanate from a shared cultural heritage. “It has rather become a process, an experience that develops in the evolution of his life-journey,” the 2014 graduate explains. “It becomes the possibility of recognising and interacting with who he is and where he is.”

As part of the project, she designed a collection of semi-nomadic objects that are symbols of the life and identity of the settled-nomad.

The collection narrates his story and functions as a series of tools to help him settle into his new surroundings. It consists of three pieces: a backpack, a handbag and a suitcase made of soft, warm materials such as natural leather, wool and wood.

The pieces can be used to carry one’s belongings and then, once the settled-nomad arrives at his temporary home, they can be used to personalise his environment.

The backpack focusses on our smallest habitable space: the bed, transforming into a woollen blanket and a small ornamental case to place on the night-table for holding personal objects.

The handbag focusses on the bedroom, as it transforms into storage to hang on the wall. The rigid outer layer of the bag together with one handle forms a book holder, and the soft main body of the handbag becomes a storage piece that can hang on a chair.

The suitcase is the largest piece and is dedicated to the environment of the home. It transforms into a woollen carpet, and the inner two pockets into a curtain and a lamp.

“The objects are movable, flexible and adaptable to different situations and environments, so that the settled-nomad doesn’t have to carry his entire home with him but can recreate it by incorporating his familiar things,” explain Palmieri.

Of her studies, she says she understands social design not as a discipline but more as an attitude – “a way of being aware of what is happening around me so that I can formulate my opinion and compare it through my projects with a broader audience. Therefore my designs can be seen as tools to communicate, to enable a dialogue about a specific issue”.

The still-emerging category of social design suits her exploratory nature. “It is a discipline that is still not really defined yet… this allowed me to find a way to define social design in relation to my work, without the constraints of labels,” she says.

She’s an “in-betweener” herself: “I position myself in between different disciplines and take many things from them – sociology, anthropology, literature, graphic design, product design… I think this in-between space is where the potential is today, there is still so much to explore.”