Landscape designer Fengjiao Ge looks into how to recycle textiles to save the tonnes of waste that goes from our wardrobes to the landfill in her thesis project Flowing Garments. A student of the Rhode Island School of Design MLA 20, Ge uses her education, skills and passion for upcycling as a force for change.

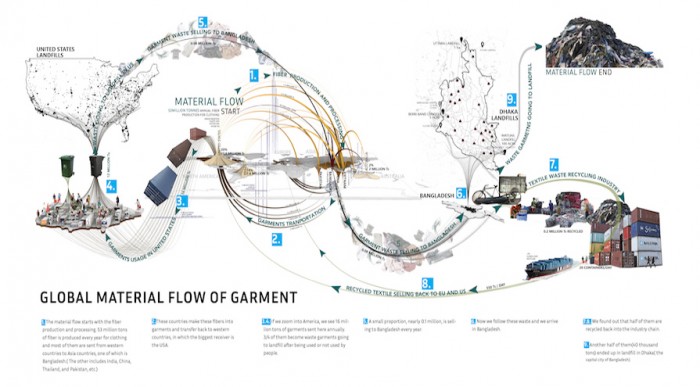

Ge took a summer class in refashioning garments and discovered the extent to which fast fashion was contributing to the landfills of the world. 53 million tonnes per annum of garment waste, which makes up a whopping five percent of all the landfill created each year. Ge began to investigate how to salvage some of the waste and create something useful with it.

“To me, landscape design is like a combination of science and art. It is site-specific, problem solving and user-oriented,” said Ge. “Before designing anything, we need research and analysis to figure out issues and make strategies.”

For Flowing Garments Ge zooms in on the particular problems faced by Bangladesh, a country that works as both the garment factory of the world and also its dumping ground. Bangladesh is paid to receive huge amounts textile waste from other countries.

Ge found out that this densely populated country is more than 80 percent flat land that suffers from terrible flooding. She developed an embankment system that uses the garment waste to create a new riverbank and surrounding ecosystem instead of concrete. Her modular system encourages aquatic plants to grow through the fabrics used in the bank and creates a living root web that connects and locks the embankment structure to the soil beneath.

Flowing Garments also proposes new construction materials made with garment waste for buildings that can be used by local villagers.

Ge has been chosen as one fo the cohort of 10 emerging designs picked for Design Indaba’s antenna 2020 as part of the Dutch Design Week programme. As one of these 10 future thinkers, Ge’s project answers one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) put forward by the United Nations (UN).

We chat to Ge about what inspired her to think garment waste as a valuable material, how activists can change the world of fashion and how she plans to use her design thinking skills to solve global problems.

Design Indaba: What made you decide to study design?

Fengjiao Ge: In China we have a different process for choosing a major. You get given a book with all the majors offered by all the universities in China. I found Landscape Design in the very last pages. I barely knew what Landscape Design was at that time. I thought it was related painting and drawing and I was interested in that, so I choose it.

How can design be used as a tool for positive change?

Design is born from problems and needs. Design can be better used as a tool for good when it is problem solving. Everything around us helps us solve problems – chairs for sitting, pens for writing and clothes for wearing. When we start to think about how to sit, and what to sit on, where to put it, who is going to use it, then a strong need or design intention can better lead our design for change.

But a whole lot of observations, research and analysis, and tests need to be done to understand the issue thoroughly and then raise the reasonable and creative strategies out of it.

Do you think design and creativity is individual, or comes from collective consciousness?

We live in the information age and we receive too much information every day. It is hard for us to not get influenced by other people. As a landscape designer, we were all influenced by Frederick Law Olmsted and his theory continues influencing us.

However, I think the most valuable part of design is the person’s inspiration and his own interpretation. It is like mutation, and the designer is the catalyst to generate new forms.

What are your design ethics?

As a landscape designer, we solve site problems and design spaces for people to use. In most cases, I give priority to function rather than form.

However, landscape design itself is telling a story about beauty and enjoyment. The aesthetic aspect of the landscape is also important. I believe that there is a balance between.

Should products always be ‘useful’?

It is hard to define “useful”. But if we are considering the general concept of useful – of course not! Then we will lose so much fun.

Chindōgu, which originated in Japan, is the art of inventing things that are useless but fun. You laugh when you see those designs, which gives them meaning. So, it is not really useless.

What inspired your project Flowing Garments?

I always have a strong interest in apparel design. Collecting second-hand fabrics and turning them into something useful is my hobby. It wasn’t until the class ‘Refashioning Garments’ that I took in summer 2018 at RISD that I realised that the shirts we wear everyday have such a crucial impact on our planet.

What exactly does Flowing Garments try to achieve?

The Flowing Garments project focuses on the recycling processes within the textile and apparel industry.

I choose to begin with the unfathomable amount of material waste modern society produces and the damage that it is doing to our environment, especially because of the amount of non-biodegradable materials we use. These enter and destroy our water, soil and air.

I am trying to raise awareness for the amount of waste and also propose new possibilities for garment waste.

Can the project be replicated in other countries than Bangladesh?

This project is specific to Bangladesh, I would say it cannot be fully replicated in other places, according to the different geological conditions and local situations. Different places have different climates, soil conditions and plants. Different places need different strategies. However, we may apply some of the ecological design principles or frameworks to other places.

How do you think designers can raise awareness for the amount of waste produced by clothing?

Here are some examples. Photographers Von Wong and Laura Francois of the responsible fashion movement Fashion Revolution made an art exhibition called “Clothing the Loop”, aiming to visualise the average amount of clothes a person wears in their lifetime.

Really, part of Danish company Kradvat, is a brand that upcycles end-of-life textiles into solid textile boards.

The manufacturing of recycled denim insulation is a zero-waste process.

I want to try and reutilise waste in landscape design and create visualisations that help people understand the scale of the problem.