First Published in

More than more aesthetics, design is increasingly about real-world functionality and significance. With the transformative ability to address the most pressing economic, social and cultural issues in the world, the inaugural What Design Can Do (WDCD) conference brought together designers, thinkers and doers working in this space.

Founded by Richard van der Laken, co-founder of Dutch studio De Designpolitie, WDCD took place in Amsterdam from 26 to 27 May. “I think we are at a moment of change and what I would like to address in this conference is that as a designer, you can do something. You can make a change in the world,” Van der Laken declared.

Though primarily a conference, What Design Can Do also took on an activist role and engaged the public directly. Various breakaway sessions, brainstorms and workshops look at how basic resources, information and the city can be made more accessible and equitable.

As a city with great cultural diversity, ornate architecture, an efficiently designed public transport system and a continually evolving sense of self, Amsterdam was an ideal host for What Design Can Do. The city’s Baroque-style municipal theatre, Stadsschouwberg, was an apt venue to host internationally renowned creative thinkers.

“The Netherlands is a very well developed country when it comes to design,” Van der Laken agreed. “Choosing Amsterdam was really about communication and creating a conference for both local and international delegates. People love coming to Amsterdam, it’s a beautiful city.”

Of the 24 speakers, highlights included Mumbai-based architect Rohan Shivkumar who highlighted that design isn’t about luxury for the rich. He spoke about the redevelopment of the world’s largest slum, Dharavi, emphasising that time shouldn’t move with design, but that design should evolve with the times.

Best known for his legendary United Colors of Benetton campaigns, Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani did not mince his words when he took to the stage. Saying that there aren’t enough creative designers in the industry, he implored emerging designers to stop designing what looks good and rather take risks. He believes that it is in taking risks that designers create the maximum output of creativity.

Speaking separately, Brazilians Adélia Borges and Paula Dib both view design as a collaborative institution where ideas should be shared and all those that were instrumental should be acknowledged. Too often designers take ideas from other cultures and communities and call it their own. Borges and Dib believe design is about talking to each other and not taking from each other.

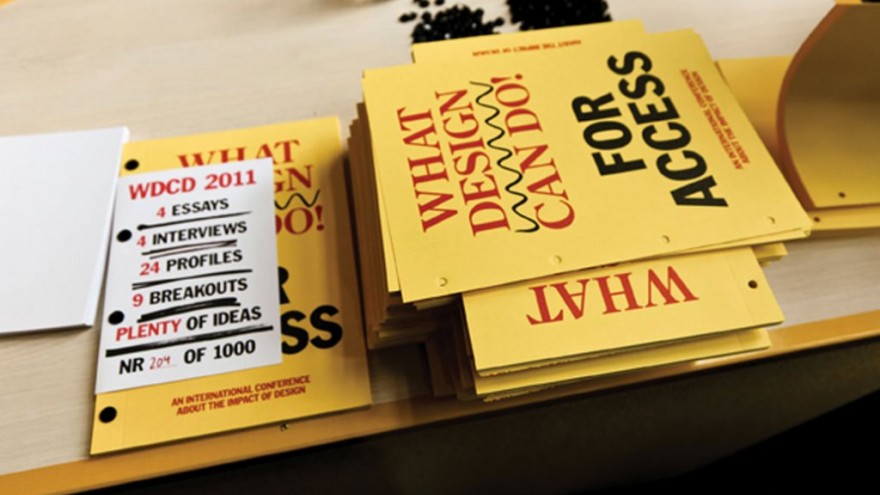

One of the most distinctive features of the conference was the making of the What Design Can Do book. Crafted as a call to action, the book is a consolidation of ideas from both speakers and delegates into one publication, through essays, interviews and profiles compiled during the conference. The entire book was assembled on site with the first copy presented to the final speaker, Li Edelkoort.

With its activist approach, the organisers of What Design Can Do have taken a simple concept and crafted a stable platform on which design can continue to grow as a pivotal force in fostering innovative solutions for economic, social and cultural concerns.