From the Series

There’s something to be said about a city in which four modes of transport co-exist in such an effortless manner. It was this realisation that answered my question on why the What Design Can Do conference was being held in Amsterdam. Besides its picturesque, old-town feel without a brick out of place, any city designed with the capacity for cars, trams, bicycles and boats shows how vital design is to the development and spirit of society.

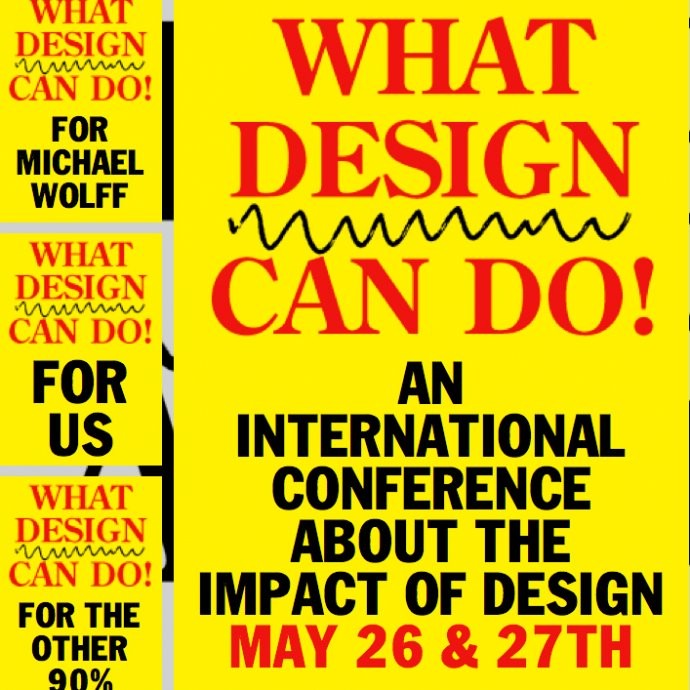

This encompasses the foundation that What Design Can Do is built on. Held at Amsterdam’s municipal theatre, Stadsschouwburg, the two-day conference, beginning on the 26 May, celebrates the power of design and its ability to solve societal problems that often dismiss design as a viable course of action. Three speakers were particularly unconventional in what they had to say, but got to the heart of the potential of design as a tool for change.

Rohan Shivkumar

It’s easy for a designer of any field to talk about their formal studies and training, and what they’ve achieved. Most will tell you about their success and what their next project is, but very few will tell you where their downfalls are and what isn’t being done. Rohan Shivkumar had no problem with that. In fact, his criticism of designers and their inability to engage with the informal was spot on.

As an architect from India, he spoke about the dire state of the country at the moment – a city of contrasts, in the midst of a rapid economic boom where the rich live opulent lives while thousands if not millions continue living in large slums and sleeping on the streets. Just like those who have benefitted from the engorged economy, Shivkumar said that designers are unable to face what is happening before their very eyes.

Instead of being shown the reality, many schools choose to teach them to speak in an American accent and look to developed countries as the inspiration for their work. Inspiration that later looks to simply sweep reality under the carpet and build mega-plexes to keep everyone away from the bad, ultimately solving no problems.

Using Dharavi, considered Asia’s largest slum that is located in Mumbai, Shivkumar showed how designers are able to redevelop an area into a sustainable and profitable living environment. Instead of building large shopping malls and business districts, which would force many out of their own homes, by looking at the design of the location and mapping the lives of those living within the community, it is possible to create a thriving community that simply needs a new way of looking at things.

Designers need to stop hiding from problems and find ways to face them head on. It’s about going beyond the formal training, asking not only what does it mean to be a designer and what does being a relevant designer mean. Without the ability to find relevance in what is really happening, then as a designer you’re sitting on a surface missing what is truly going on down below.

Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFares

While short in stature, Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFares has in many ways been credited with rejuvenating the arts in the Middle East. But it was the way in which she did it that was most unconventional– if not a little puzzling. On first hearing that Smitshuijzen AbiFares was a typographer, and being interested in typography, it was with interest that I listened as she spoke of using typography as a means to engage the Middle Eastern world and to help bring the East and West together while uplifting and connecting people to their Arabic heritage.

She explains, as someone who has had the opportunity to live in the Middle East and now in Europe, that while there was a booming design culture, specifically in typography around the globe, when she was in the Middle East there was no link to what it meant to be Arabic and living in the Middle East, and contemporary design. It was through the creation of the Khatt Foundation that Smitshuijzen AbiFares dedicated herself to the advancement of Arabic typography and design research in the Middle East. “It was about finding a new design philosophy,” she explains during her presentation.

With a need to promote design in the Middle East and open people up to its potential to bring communities and culture together, Smitshuijzen AbiFares wanted to start a dialogue between the typography of the East and the design of the West because she always found that Arab designers looked to the West for inspiration, but rarely their own culture and heritage. The designers in Europe were more skilled in the art of typography at the time so it seemed an easy fit to allow the two to work together to bring life to the Arab heritage.

It was fascinating to listen as she spoke of using a field of design that has rarely been seen as anything more than the shaping and arranging of type, and instead began to use it as a means to break boundaries between designers and the old traditions of Arabic script as a religious and political tool. By being able to shift the understanding and mindsets of designers in the Arab world and showing them that inspiration lies right before them, Smitshuijzen AbiFares has been able to generate a new excitement, placing a spotlight on design in the Middle East.

Oliviero Toscani

To say that I am somewhat frightened by this man is an understatement. And I’m not even sure that frightened quite describes it. Oliviero Toscani is a man who speaks his mind without fear because he believes that what he has to say is important to the world of design. Not due to arrogance, but more due to his wealth of experience and uninhibited sense of expression.

As an iconic photographer, Toscani has been behind some of the most controversial campaigns to hit the public eye such as the Benetton campaign and Lolita clothing. But he doesn’t care what people have to say because all he’s doing is saying it like it is and showing people what many already see. Except, he has the courage to capture it in one eye-opening photograph.

Listening to Toscani speak was like listening to someone who in many ways has lost faith in the designers that now take the industry by storm. Fearless in his commitment that design is about taking risks and having the courage to do those things that normally wouldn’t be done, he said that those who talk about their creativity have failed to be creative.

“I’m afraid of people with ideas,” he said and added that he can have thousands of ideas at any moment, but that doesn’t mean he’s creative. For Toscani, creativity isn’t about coming up with the idea; it’s about constantly creating because what’s the point of having ideas if you never do anything with them?

One of the shortfalls of designers these days is that a programme on some computer can do everything. He explains it by saying that technology justifies designers’ creative inertia. That technology creates lazy designers. Quite a remark when considering some of the speakers before him had said how technology, particularly those programmes, had created more opportunities for designers in taking what they do to greater heights.

But Toscani was having none of it and even went as far as critiscising the “people who tell you what to design”. “I’m a art director,” he sais incredulously as if not even sure what that means. To Toscani, art is the highest form of communication so how can he or anyone else possibly tell people how to create art? There is no doubt that this design great got a few people talking and some maybe even a little rattled, but you have to give credit to a man that is able to tell designers they are mediocre and still get a rousing applause at the end.