David Goldblatt is, arguably, South Africa’s most prolific photographer. Best known for his “slice-of-life” photographs capturing the cultural and social essence of day-to-day life in South Africa, Goldblatt’s work serves as subtle commentary on the complexities, intricacies and nuances characteristic of life in this country.

The grandson of first-generation Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, Goldblatt was raised rather orthodox in the town of Randfontein outside Johannesburg. His Jewish upbringing, and life in an Afrikaans community would be two factors that influenced the way Goldblatt approached his photographic work, with interesting results.

Goldblatt became interested in photography at a young age. He was particularly inspired by the photography in the magazines of the time, like Life, Look, Parry Match and Picture Post. In the days before television, Goldblatt points out, these magazines were millions of people’s visual window on the world, also his.

These magazines and the growing popularity of the photo essay as a form of visual, social commentary intrigued Goldblatt, who started dreaming of being a magazine photographer. In hindsight, he says, he realises that upon matriculating in 1948 he should have gone to England and worked as a tea boy at a magazine like Picture Post. “I was advised to do this but I just didn’t have the guts, I was a Jewish boy from Randfontein,” Goldblatt admits.

Goldblatt also had family obligations at home. His father had taken ill, forcing Goldblatt to take over the reigns of the family menswear shop. During this time photography was just not just a hobby for Goldblatt, but an obsession and he did occasionally submit his work to publications. He tells of the photographs he took of the ANC’s 1952 Defiance Campaign. Goldblatt sent the pictures to Picture Post in England, who were keen to have a visual reference of the resistance campaigns in South Africans. But Goldblatt’s take on the event were not well received.

Never one to be deterred by criticism, Goldblatt set about improving his skills throughout the 1950s. Goldblatt started working methodically through various textbooks on photography, including the writings of Ansell Adams. It was also while managing his father’s shop that Goldblatt completed a part-time BCom degree through Wits University.

In 1962 Goldblatt’s father died, which left him free to sell the business and really focus on photography. The avant garde Town magazine was popular during this time which further motivated Goldblatt to hone his photography skills. Goldblatt also sent some of his work to Norman Hall at The Times of London, the “doyenne of photo critics” at the time.

On 15 September 1963 David Goldblatt officially handed over the shop keys and became a photographer. He describes this moment as “very liberating” and he has never looked back.

Goldblatt’s first photo essay was of West Street in Johannesburg. This is an arterial street in the white CBD of the time that black commuters had to use. Through the years, Johannesburg became one of Goldblatt’s most photographed subjects though he never consciously set out to photography this city, “it just happened”.

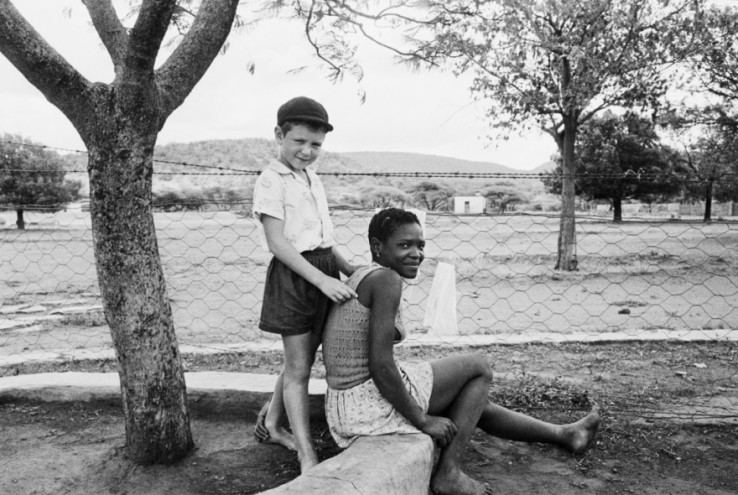

As he set about capturing the pulse of the simply, everyday things that defined life in South Africa, Goldblatt realised two things. The first was that he doesn’t like working in a studio and he also doesn’t like photographing events. Rather, he found himself becoming increasingly interested in the conditions and values that lead to specific events and how it manifests in the lives of ordinary people. This interest would go on to characterise most of the work that Goldblatt produced in his 50-year photographic career. In his own words, Goldblatt considered the theme of his work to centre around South African value systems, the simple things that lead to more fundamental things.

Later the Marico Bushveld, the world of author Herman Charles Bosman, would come to feature prominently in Goldblatt’s work as he spent days exploring this area and giving it a picture to the much-loved stories of Bosman. The gold mines of the West Rand were an intimate part of Goldblatt’s life and something that he spent a lot of time photographing. Despite its physical closeness to Goldblatt’s own world, it somehow only existed on the periphery. Much of his work of the 1960s focussed on life on the mines, the activity that collectively formed the backbone of the South African economy.

A watershed moment came for Goldblatt when he became conscious of the writings of Nadine Gordimer.

I found her first short stories to be very exciting because they spoke about the intimacies of experiences that provoked my photography.

Goldblatt asked a mutual friend to introduce him to Gordimer and a collaboration followed shortly, On the Mines with Gordimer writing the text accompanying Goldblatt’s photographs.

“Structures” is another one of the themes in Goldblatt’s work. He set about capturing the “peculiar honesty of South African structures” by looking at things like the architecture of churches, public buildings and monuments. Goldblatt explains that much of South African culture can be better understood by looking at our architecture and structures. Goldblatt did extensive research and writing on the structures and architecture of the Afrikaans protestant church.

Throughout his photographic career, Goldblatt has always followed his instinct, mostly with outstanding results. Having always used photography as a device with which to analyse social, political and cultural structures, there are countless layers of interpretation to Goldblatt’s work.

Goldblatt’s work has always revealed something about the lesser-known aspect facts of life in South Africa. He has an uncanny way of getting to the heart of the matter with a unique honesty and directness.

A major exhibition of Goldblatt’s work can be seen at the South African Jewish Museum in Cape Town. Kith, Kin, Khaya, which runs until 11 January 2011, includes some of Goldblatt’s more prominent works with their typical honesty capturing the texture of life in South Africa.