Mariam Kamara's approach to architecture is as much about sociology and anthropology as it is about building.

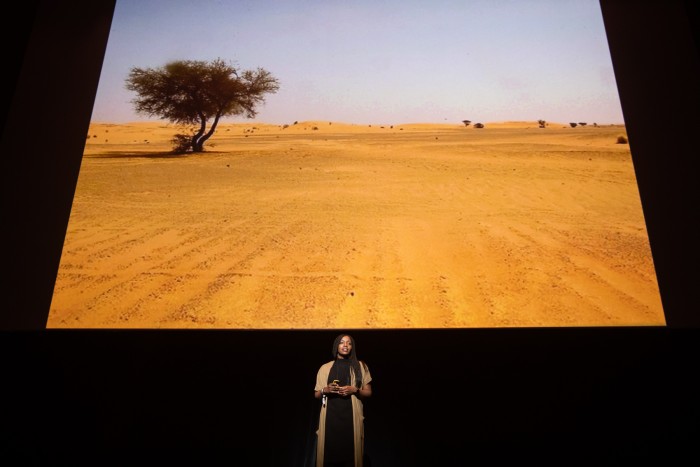

A firm believer of design's significant role in the functioning of society, she kicked off her Design Indaba Conference 2019 talk by painting a picture of her home country, Niger, giving a clear portrayal of its context.

She explained that the land-locked country's dry climate and flat terrain has economic implications of its own. In addition, with a largely Muslim population, there are conservative-leaning nuances too that must be considered. Another challenge is presented in being restricted to just 3 locally-available materials: recycled metal, compressed earth bricks and cement.

All these factors intrinsically inform the projects Kamara and her studio Atelia masomi have taken on.

Niamey 2000 for example, is a housing complex inspired the cultural behaviours and habits that takes into consideration the communal nature of the local society. Made with compressed earth bricks, it responds to the city of Niamey's need for increased density without violating the sense of privacy that the locals covet.

The Hikma Religious and Secular Centre in Dandaji on the other hand, is a de-facto response to a very serious concern. With Niger having one of the youngest populations globally, Kamara says a problem presents itself in that this population has "very little access to education and a lot of access to religion," making way for an intense situation that could potentially result in radicalisation.

With a brief to create to separate projects, the team felt strongly that religious institution and educational instritution should be combined in order to aid agency between the two.

"All of a sudden the relationship between the two, which nowadays all over the world, really you have this confrontation between secular knowledge and religion," she says.

Addding, "And so for us that was an opportunity to address that and help de-escalate that tension in just a very benign, very simple way."

Beyond this, the centre also enabled the team to devise new ways of producing old forms, given that the project took its initial cue from reviving a derelict mosque. Instead of starting anew, they used this as an opportynity to produce new interpretations of old techniques.

She ackowledges that a big part of her studio's role became fixing: "We were starting to feel as though we were becoming repairmen and women, where every time there was a project, all of a sudden there were all these opportunities for fixing something or for making a contribution towards making something better."

Kamara's talk concluded with the revelation of the Artisan's Valley project in the city of Niamey, which is a collaboration between Atelier masomi and Design Indaba. Inspired by the work of Nigerien historian and politician Boubou Hama, it aims to create a public space that can sustain various social functions. The greater goal is to bring together both sides of the valley, a divide between the 'haves' and the 'have-nots' which was perpetuated beyond colonial rule.

Like her other projects, she sees this as a means to foster a more positive perception of her home country. "I think it's a great step towards changing the narrative of a place that has been deeply negative," she says. All the details of Artisan's Valley are available here.

Watch the full talk:

Watch more talks: