First Published in

Razia Sultan

A 13th century ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, Razia is the central Islamic female figure from the annals of Indian history. Out of keeping with all tradition, she was groomed for the throne in lieu of a debauched older brother. She refused the epithet of Sultana, with its connotations of power derived from a male monarch, and styled herself Sultan – a ruler in her own right.

Historians quibble about the nature of the relationship with her Abyssinian slave and putative lover Jamal-ud-Din Yaqut, and her matrimonial alliance – political accession? personal agenda? – with childhood friend Malik Altunia.

But there is concord that in an abbreviated four year reign, Razia Sultan proved herself an able statesman aligning disaffected factions, a religiously tolerant leader embracing a disenfranchised Hindu population, a pioneer of education and a patron of the arts, and in sum, a brave and charismatic queen.

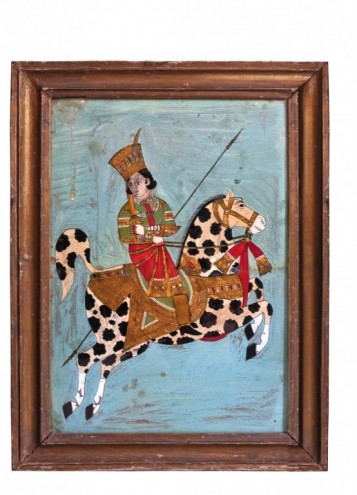

Rani Laxmi Bai

Immortalised in a Hindi schoolroom verse, with an oft-quoted couplet – She fought like a man in battle / She was Jhansi's queen – Rani Laxmi Bai has attained the iconic warrior status that is usually reserved for men. She was a focal rallying point for the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, India’s first unripe rebellion under the yoke of British colonial rule.

Married into royalty, to Maharaja Bal Gangadhar Rao Newalkar of Jhansi, Rani Laxmi Bai’s familial life was marred by tragedy. Her heartbroken husband died shortly after the demise of their infant heir, leaving the reins of an uncertain succession in her hands at the tender age of 18. The Rani of Jhansi adopted a young son and rode out to battle when the British denied him his legitimate contention to the kingdom.

She died on the battlefield, but an image of her flourishing a sword astride a rearing charger, lives on in the collective Indian imagination.

Sarojini Naidu

The Bharatiya Kokila (nightingale of India) sung the sorrows of a nation struggling to define itself in a time of strife. Her claim to queenliness is meritocratic rather than aristocratic – Sarojini Naidu was the first female President of the Congress, the political party that agitated for the cause of Indian independence. She counted in her cohort, freedom-fighting bluebloods like Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

Raised in a family where education and poetry were privileged, she completed her college degree, and was even valedictorian, as a very precocious 12-year-old. Because of an intervention against an inter-caste love match, a tender Sarojini was bundled off to England for further study, but she returned to wed her paramour Dr Govindaralu Naidu in the face of dire opposition.

Instead of cloistering herself in an ivory tower of intellectual isolation, Naidu chose to travel the country lecturing on pressing issues of social reform, female emancipation and the dignity of labour. Her works emulate her hero, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, in their progressive, humanitarian exhortations.

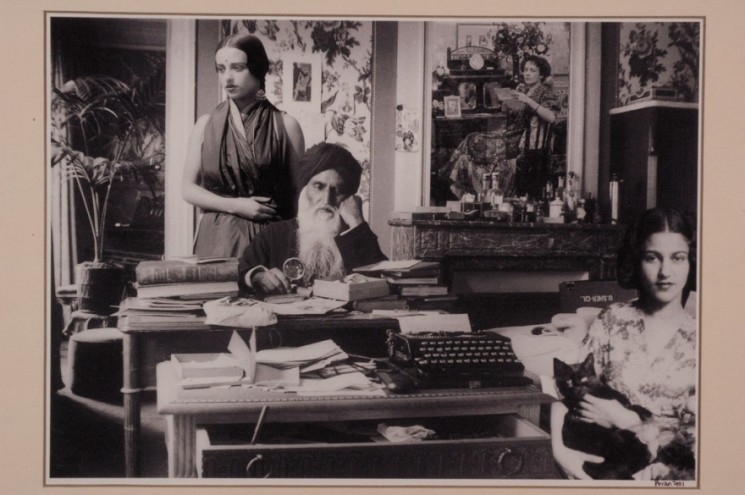

Amrita Sher-Gil

What Frida Kahlo was to post-revolution Mexico, and Virginia Woolf to mid-war England, Amrita Sher-Gil was to pre-independence India. Her canvases are a pastiche of vivid minimalism that concurrently elegise and energise her primary subject: women.

The elder offspring of a patrician Sikh father and a Hungarian Jewish opera singer, Sher-Gil shuttled between Hungary and India through her childhood, and subsequently attended the École des Beaux Arts in Paris at 16. Influences as dissimilar as Paul Gauguin and Mughal miniature find a place on her palette.

She brought a version of Bohemia with her when she moved back to India. An accommodating marriage to a first cousin, and gender-indiscriminate liaisons sparked scandal and gossip. But Sher-Gil’s enduring love affair was with India, and her travels and travails across the subcontinent are documented in the bold colours and sweeping strokes that typify her mature work.

Gayatri Devi

A celebrated classical beauty, the Princess of Cooch Behar who became the third wife of Maharaja Man Singh of Jaipur, led a life of unimaginable opulence. Panthers, polo, palaces, private jets, were all par for the course. When princely purses were abolished in the fledgling Indian democracy, the Maharani found a new calling in politics.

Gayatri Devi’s landslide victory in her first Parliamentary elections had the distinction of featuring in the Guinness Book of World Records; she won by the largest margin ever recorded, a clear 192 909 votes out of 246 516 cast.

She also appeared on a list of the “Most Beautiful Women in the World” in Vogue. That the recent obituaries referenced such trivia at least as frequently as her first political win, is an ironic yet fitting tribute. She occupied a nebulous interstice of politics and privilege, but it was her glamour and her grace that won hearts... And votes.

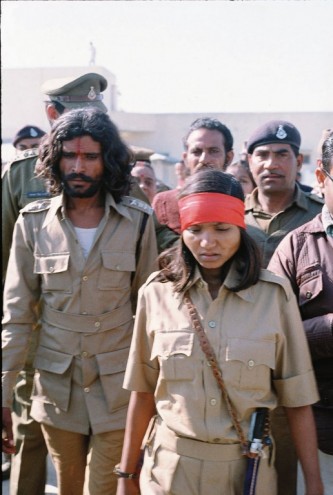

Phoolan Devi

When bedtime approached and children fussed, mothers in the Indian heartland had a quick admonition to send kids scampering, “Sleep now, or Phoolan Devi will come for you.” The bogeyman and Wee Willie Winkie can’t compete with India’s Bandit Queen – while the chronicles of her life are part folklore and part hyperbole, her reign of terror across the central states was only too real.

As a low-caste girl child raised in a village hidebound by tradition, Phoolan Devi railed at the entrenched inequities and her own lack of agency. Her inchoate rebellion was horrifically quashed – a child marriage, domestic abuse, and repeated rape drove her to justice beyond the law. As a dacoit (bandit) she initially targeted upper-caste landholders, symbolic oppressors of her wretched past. The carnage soon extended past personal vendettas and shed innocent blood.

Eventually she chose to effect change within the system, as an elected Member of Parliament. But her violent past caught up to her, and her term in office ended brutally and abruptly with her bloody assassination in 2001.