From the Series

First Published in

The 10th of May 1994 was the most visible and significant day in our history. The inauguration of President Mandela attracted visiting diplomats from 140 countries. Many millions of television viewers worldwide tuned in for the auspicious event. Only tragically, when our big moment finally arrived, we found - to our utter astonishment - that we had nothing remotely appropriate to wear.

We did of course have clothes on. Yet strip away everything that was borrowed, along with the sprinkling of historically-frozen ethnic styles, and look for anything on our bodies that expressed who and where we were at that moment, and South Africans stood stark naked before the universe.

Of course it would have been far more powerful and glamorous if we could have used this million-photo opportunity to showcase a contemporary and original South African style to illustrate our miraculous transition to democracy. A Spring Collection of rainbow coloured garments for the so-called Rainbow Nation, if you like. But such a collection simply didn't exist. What was absent from those photographs was just as eerily absent from the racks of the country's boutiques, chain stores and the wardrobes of its people. South Africans were suddenly confronted with a pressing question: WHY?

The answer is not simple, but rather a result of the social and political circumstances of our history. It requires a complex investigation of half a millennium of fashion history - and all the political, geographic and social factors that shaped that process - at Africa's southern tip.

Over the past few centuries, hardly anyone gave the slightest thought to a fusion of western and African dress. Traditional costumes were still worn ceremoniously in the rural areas, and were vaguely recognisable from the dusty showcases of our museums, where they were showcased with the same exotic curiosity as the country's splendid fauna. But for the most part, newly urbanised dwellers had adopted the European dress codes imposed by the colonisers, complete with their class-based hierarchies. There had never been a reason to fuse these styles. Europe and America were what you aspired to and wrapped around your body, and Africa was a cheery, timeless postcard. Or was it?

Unsurprisingly, the scant texts that exist on South African fashion history are almost devoid of black people. Tracing the evolution of style in this country is the job of a private detective looking less at what was presented as much as what was purposefully hidden. Apartheid had made sure to erase all evidence of black fashion to the point that one was tricked into believing it didn't exist. But for many people, this is an extremely offensive hypothesis.

As far back as the 11th century, there is evidence that skilled civilisations in this region produced both garments and objects of adornment. It is only in the past decade, however, that a handful of visionary designers have been drawing on what has gone before and what surrounds us, and weaving those threads into contemporary clothing.

After gorging ourselves for decades on shame and denial, democracy induced a sudden hunger for identity. The transformation of South African fashion in the few seconds of fashion history that have passed since then has been nothing short of revolutionary.

Initially, the euphoria of a Rainbow Nation produced much folklorish design. We had our fair share of sequinned SA flag ball-gowns… Gradually, however, we have witnessed more subtle and sophisticated expressions of sartorial identity, increasingly reflecting more diversity. In observing this amazing evolution of a STYLE OF OUR OWN, I have identified some themes that may be useful.

Origins

A few years ago, when Vanya and Thando Mangaliso launched Sungoddess, I found the work folkloric and overly historical, but the success of the label has proved me wrong. They have shown their work from Sweden to Italy and Japan alongside designers like Galliano and Westwood. The collections set out to reinvent historical styles in a contemporary idiom.

Vanya explains: "We had these beautiful Xhosa clothes from our childhood, so we wanted to tell stories and influence future generations by changing how South Africans perceive themselves."

"If you were living in the Eastern Cape in the 1700s, you'd have taken a piece of animal skin and wrapped it around the body. The whole concept of wrapping and layering is an African phenomenon," says Vanya, and the technique is also evident in the work of designers like Maya Prass, Amanda Laird Cherry and Clive Rundle.

Yet if we want to see that which is African in local fashion, we may have to look beyond the obvious. Even Jacques van der Watt will concede to African influences in his work, but never without a fair deal of processing and deconstruction. Another designer who has masterfully interpreted many traditional and urban styles is Marianne Fassler.

Culture clash, late 1600s

While it by no means marked the beginnings of South African Fashion, it is useful to place ourselves at the Cape in the late 17th Century. Try and picture the absurd apparition of Jan van Riebeeck and his entourage as they stepped off The Reiger, from the perspective of the original inhabitants at the Cape.

One can only imagine the utter incongruity of these Dutch colonists, clad in their austere black and white garments, with hand-made lace collars and buckle boots. Despite the fact that this event would indelibly mark South Africa as one of the planet's most curious melting pots, the 1700s were a rather dull time for fashion in this region. During the 1800s, Trekboers and traders began venturing into the interior, bringing with them cloth and beads for trade and styles of dress that were to influence the fashions of the interior. Indeed, the ethnic styles that we take for granted as historical were trends that resulted from this exchange.

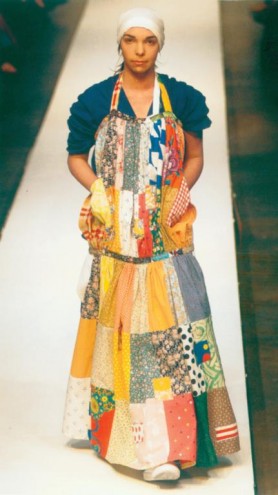

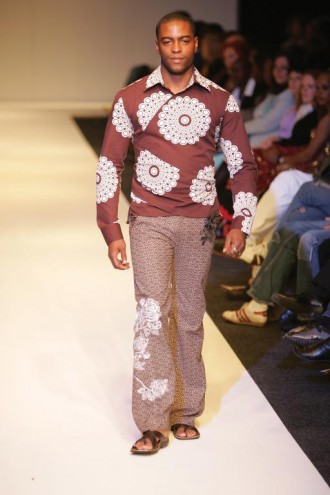

Looking back through the archives of SA Fashionweek, a tribal thread unravels. Both cloth and ethnicity emerge as inspiration. Some interpretations are literal, others are more expressive.

Cloth

South Africa as a region was always textile poor. It was not until the late 18th Century that we began cultivating cotton. Even today most designers work solely in imported cloth. However, there are some cloths that are so deeply woven into this country's history that we may consider them our own.

Perhaps the one with the longest history is Salempoor, woven in Salem, India, and included in the first orders placed by Van Riebeeck at the Cape Colony. It was only much later that this cloth was adopted as traditional dress by the Shangaan and Venda tribes, and is now known colloquially as Venda Stripe. It has appeared in various forms in contemporary collections, and is used in what Stoned Cherrie's Nkhensani Nkosi describes as "a Contemporary Afro Urban aesthetic." Of course no cloth is more widespread than IsiShweshwe. First imported by German Missionaries from central Europe in the 1800s, it has since been adopted for traditional and daily use by most South African cultural groups, and thus might be the most democratic of all South African cloths. It is still only printed on archaic narrow copper plates at Da Gama textiles in the Eastern Cape, who bought up the machinery from the Manchester factories in the 1970s. With democracy this cloth became so popular, both with designers and rural dwellers, that at times the mills couldn't keep up with demand. Because it was everywhere, designers even customised the fabric in various ways in order to make it their own.

Yet nothing has been as widely referenced as the Xhosa A-line skirt. Over the past decade, this horizontally striped skirt has emerged as the most iconic item of South African dress. So much so I have wondered why it hasn't yet appeared on a postage stamp.

To understand its origins we must explore the evolution of colonial fashion, which too was ever changing. Until the mid-1800s, colonial women had worn as many as seven petticoats to support their vast skirts. But in 1870, crinoline hoops liberated women from these petticoats. The famous stripes, which were hand-stitched in binding, were initially a take on these hoops. Similarly, the neck rings and concealing style worn by Ndebele women may possibly have been an interpretation of high-collared late Victorian styles. We can only guess…

Migration

During the 19th Century, the Great Trek forged what was perhaps the first indigenous style among white South Africans. Due to the durability of the fabric, Voortrekker women chose 'SIS' or chintz for their simple Empire-line peasant dresses. Despite its political incorrectness, as the new democracy matured, so certain designers felt more comfortable owning this heritage and exploring it in their collections.

Gideon came under fire for paying homage to this style and to the Afrikaners in the concentration camps of the Boer War in his 2003 collection Remembrance. He states: "There are so many diverse cultures in this country and we have to embrace all of them. I'm proud to be an Afrikaans guy. It's not about politics. I just wanted to contribute."

Other indigenous items that emerged from the Great Trek were the witkappies, patchwork, velskoen, klapbroeke (leather trousers), smoking hats and tobacco pouches - all of which have been reinterpreted by modern designers who dare to explore these politically incorrect references.

Nature

For many designers, a sense of place is created less by historical or ethnic referencing but by the colours and textures of the landscape. We have thus seen: feathers, indigenous flora, gold, leopard print, porcupine quills, brightly dyed ostrich skins, neon-hued springbok hide, and inspiration drawn from patterned animal skins like zebra. All these references help forge an aesthetic that is distinctly, while not obviously, South African.

Street

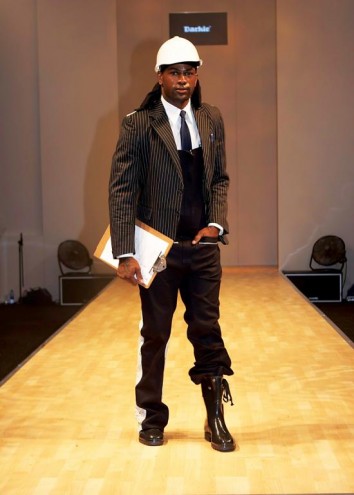

Much inspiration for designer collections comes from the eclectic juxtaposition of styles we see on our country's streets. Even the way hawkers and hobos style themselves provides inspiration. While some argue that street, and particularly township style, is merely an appropriation of American or township styles, others disagree. Having grown up in a household, where his mother sold second-hand clothes from her garage, designer Themba Mngomezulu works in recycling, displaying just how African a second-hand European aesthetic can be.

Says stylist Felipe Mazibuko: "We were brainwashed to feel inferior about our cultures so we've taken elements from other places and made them our own. But we've done it on our terms. When we wear All Stars we're taking the piss out of them… That's why we wear them without socks or shoelaces. It's as though we're saying: 'You've taken so much from us now we're gonna take what's yours and own it!'"

Resistance

You can't look at fashion in this country without looking at themes of struggle and war. Military-inspired collections and the use of camouflage fabric pay homage to this country's struggle for liberation. Vintage resistance posters have been reinvented as hip, contemporary style. The images of Struggle heroes on T-shirts alone tell a whole history of Apartheid and are an alternative to wearing Che Guevara T-shirts.

Identity

With the birth of democracy, South African youths in particular were hungry to express their identity and so a new patriotism found its way into popular iconography. We wanted to reject a culture of borrowing, and wear South African icons. Maps of Africa became mandatory and patriotism was expressed literally in our obsession with national teams, with soccer culture and sport generally. In our quest to know who we were, we paid homage to musical heroes and expressed a deep nostalgia for the Fifities as immortalised on the covers of Drum magazine. Even our cities saw new declarations of devotion…

Afrofuturism?

There was a time when I worried that we might be stuck in a particular ethnic aesthetic. Lately I have grown less fearful. Particularly through the use of textiles, local designers have drawn on the rest of the continent in an attempt to forge a brave Pan-African identity. It is less a case of Africa defining us than us defining a new Africa of tomorrow. Some work is grand and theatrical, some sharply tailored and wearable.

After a process of searching for identity, collections have emerged that are bold, and infuse African and global styles in ways that we might never have expected a decade ago.

As a nation, I think this has been very good for us. It has restored a sense of pride and infused us with hope and excitement. I once asked Amanda Laird Cherry if she thought clothes could heal. We had been talking about the range of traditional Zulu Mblaselo pants she'd created with the help of a traditional Zulu tailor Mr Mbatha. She spoke about how careful she'd been to show her references and how respectfully she had borrowed them. Amanda thought long and hard before she answered. "I think that's the essence of what I do," she said. "By putting these things out there and doing it in a way that's not an airport curio style, but rather relevant and respectful, I think I'm somehow working through my deep sorrows of Apartheid in my clothes."

Over the past decade, the local fashion industry has been revolutionised in many ways. Not only in terms of reclaiming identity, but behind the scenes, where the chain stores that monopolised the industry have made way for smaller independent designers. From a nation with nothing to wear other than what we had borrowed from afar or from history books, we now have rather a lot of wardrobe options. We have also shown that we have a truly unique contribution to make to the fashion planet.

About the author

An award-winning South African author and journalist, Adam Levin has published three books: The best-selling Wonder Safaris, The Art of African Shopping and Aidsafari, and is working on his fourth. A Revolution of Style: The History and Democratisation of South African Fashion - from which this piece derives - is a celebration of the 10th South African Fashionweek to be held in July 2006. The book will be launched in July 2007. He is currently covering India Fashionweek and having tea with Bubbles, the Maharajah of Jaipur.