There is literally never a dull moment at Design Indaba Conferences – and this year was no different, with non-stop revelations, insights, humour, entertainment and profundity.

The first presenter of the day was Jakob Trollbäck, creator of the communication language for the Global Goals, or UN Sustainable Development Goals. His chief challenge? Finding a simple, relatable way to convey the global agenda of the UN without boring or depressing end users. The result is a bright, idealistic take on solving the world’s most pressing problems – a meta-crisis, as Trollbäck puts it – using visuals everyone can understand and become invested in.

“Complexity is good – it gives us so much, but it’s hard to understand,” he said. What do we need to make these development goals happen? “We need openness, new perspectives, sense-making, an inner compass and compassion,” he pointed out. CEOs who lack those qualities are not worth working for. His ‘periodic table of change’ is a hopeful guide to future action.

Mazbahul Islam’s heartfelt presentation followed. As a business graduate, he dreamt of making a lot of money, but then had to make a hard decision. As the only son in a middle-class family, did he have the right to quit a stable job to pursue a career as an entrepreneur? His ideals won out and a medical emergency close to home persuaded him to focus his attentions on providing low-cost emergency medical care in rural areas in his native Bangladesh. Safewheel, his project to roll out tricycle mini-ambulances and services to help rural communities, has saved thousands of people to date.

“During the course of my work, I learnt two lessons,” he says. “It’s never too late to decide who and what you want to be; and only you can decide how big or small your challenges are.”

Up next was Index award-winner Natsai Audrey Chieza, whose synthetic biology appears to be at the forefront of design for the future. She contends that we can take molecular level design and create systems that enable us to apply this research in the real world. “Design is becoming more than human,” she asserts. “Microbes are becoming material, so we need more tools to better understand these co-dependencies outside of science.” We have cultured only 2% of microbes to date, so there is a lot that is still to be discovered, she says. In the meantime, we are harnessing the properties of microbes to solve problems within a variety of industries, from fashion to construction.

After a lunch break, Satyajit Das, the founder of Architecture Social Club, took to the stage. He asserted that design helps you to do things you never thought you could do. He and his cohorts work across disciplines to tell stories and create immersive experiences for audiences. “I really love chaos, especially beautiful chaos,” he told the audience. “I think it’s our job as creatives to find beauty in chaos.” The presentation concluded with a wonderfully mesmerising audio-visual interlude.

Enni-Kukka Tuomala, empathy designer and artist, spoke next. She told the audience that empathy is the most radical of human emotions. “We need to fight what former president Obama called the globalisation of indifference,” she said, arguing that design can use empathy for the large-scale reform of politics, healthcare and education. She pointed out that power and stress reduce our capacity for empathy, suggesting that they limit our capacity to identify with others. Could a balloon start an empathy revolution? Balloons are among the many tools Tuomala uses to break down barriers between people. She had the audience blow up a pink balloon found on each seat, meditate upon what was preventing us from connecting us to others, then release these feelings by releasing the balloons into the air (resulting in delightful mayhem, a lot of giggling, and the release of tension). She said something as naïve and pure as a balloon can have a profound effect – even on Parliamentarians in Finland, where she has worked.

Royal College of Art MA graduate Anna Talvi took to the stage thereafter, to discuss her microgravity wear for space travel. She told us about some of the challenges people face in space, most notably how the shape of the human body changes significantly. Torsos become puffy, muscles experience wasting, and we have the obvious challenge of having no washing machine or creature comforts in what is in effect a floating science lab. She said designing for ‘space bodies’ was a significant challenge. “We humans were not really designed to be in the floating world of space. But we don’t just want to survive there; we want to adapt and thrive there,” she explained.

Her future-focused talk was followed by Honey & Bunny’s rather zany, slightly Dadaist performance, which consisted of a philosophical disquisition on the positions humanity has taken regarding design over the centuries (from a variety of ideological perspectives). They played with their food and challenged audience perceptions of table manners, how we use implements, how we consume food, and how we talk about food and design. They concluded their performance by writing an entirely new design manifesto. “We could change everything as designers – we could rebrand beauty, redesign objects, rules and conventions. We could change everything if we wanted to,” they reminded us.

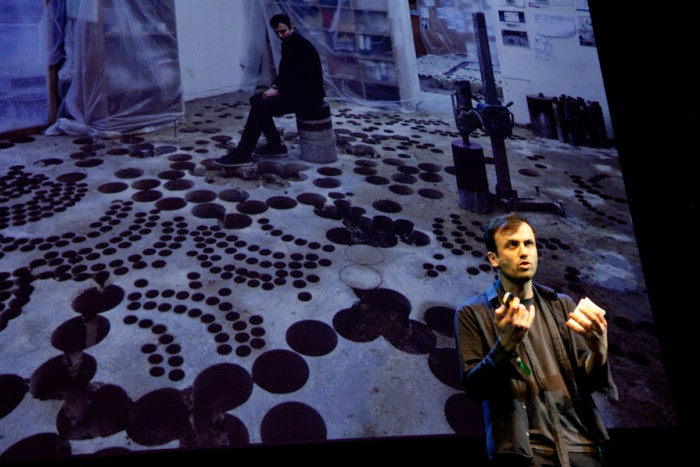

Next on the agenda was Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, who introduced us to the jute sacks he repurposes for his art – he takes them everywhere with him, keen to create art in different environments. “I’m an artist with no shame. I go into any space and ask if I can work there – factories, railways and so on,” he said. “Sometimes people say no, but mostly they say yes.” Context is everything to Mahama, and irony and anti-colonialist commentary inform his socially oriented artworks. “As practitioners, when we produce, it’s very important to go back to the idea of the real and to consider everything around us,” said Mahama. “One must also not forget that change rarely happens immediately. It takes time. We need to make change for the future generations and not for right now.”

Considering what drives him to make his totalising artworks, which rewrite the history of colonialism, he says a lot of the projects he undertakes emerge from the spaces in which he finds himself, whether in Ghana or abroad. A particularly touching project is repurposing old aeroplanes to that they can be used as classrooms in Ghana. Children love these classrooms and some even make model aeroplanes as a result.

Research-driven material explorer Elissa Brunato’s presentation told us about the necessity of reinventing sequins – most are made of PVC plastic and are toxic to both workers and the environment. She set out to create bioluminescent sequins from cellulose. These compostable sequins don’t need dyes or chemicals – they have a natural shimmering quality that does not fade over time. “Humans have a very interesting relationship to shimmer, which is linked to our innate need for water,” she said. Perfectly adapted to a fashion industry starting to take sustainability more seriously, these sequins are a beautiful addition for embroiderers – or anyone who loves a little bling.

Multidisciplinary designer, Paul Cocksedge was up next. He gave us a whistle-stop tour of some of the striking work his design studio has done, with the cherry on top being a project to transform a Cape Town River Garden with a gorgeous pedestrian bridge! The city will benefit from Paul’s addition to our ‘Do Tank’.

After tea-time, and before the final two speakers took to the stage, the winner of the Most Beautiful Object in South Africa competition, sponsored by Mercedes-Benz this year, was announced. The general public voted for Izandla Zethu’s Delicate Bracelet. The bracelet was made using corrugated iron, a material commonly used to build shelters in informal settlements. It symbolised the transformation of poverty into beauty through design. A worthy winner!

The second-last speaker of the day was Rick Brim, chief creative officer of adam&eveDDB, who was introduced by D&AD CEO Patrick Burgoyne. He started his presentation with a sobering fact: £18.3 billion is spent on advertising every year, but only 4% of ads are remembered positively, with 7% remembered negatively and 89% barely noticed or remembered. How, then, to engage with people? The trick is to a trend, find a unique angle, or simple redefine the zeitgeist yourself – and be better than anyone else when it comes to understanding how human emotions work. No easy task – but Brim and the adam&eveDDB agency are past masters at tugging at the heart-strings with their very much ‘out there’ ideas.

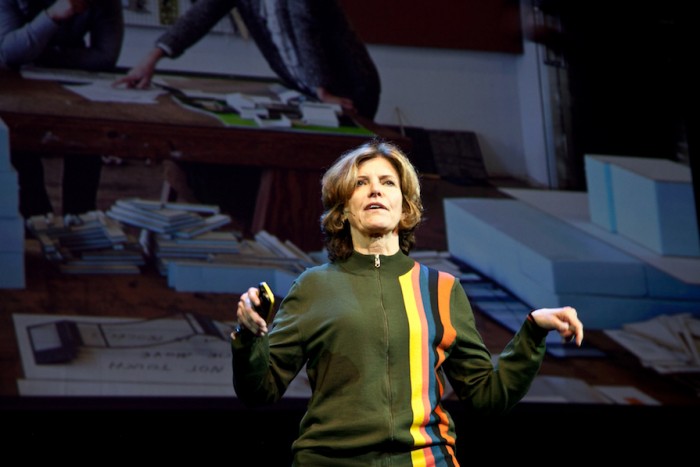

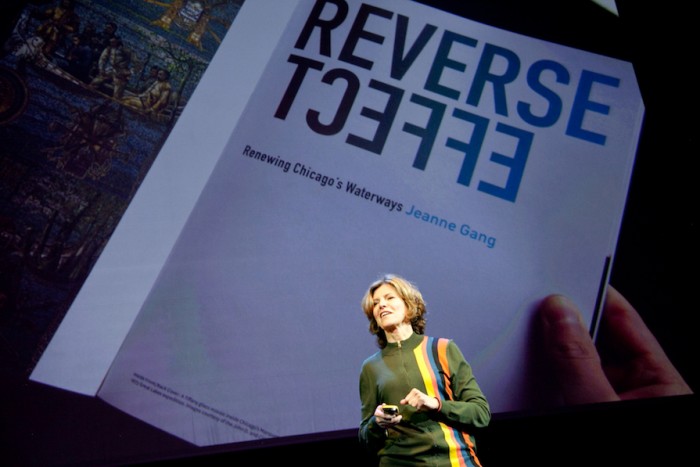

The final speaker of the day, architect Jeanne Gang, was refreshingly modest for one of TIME magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world in 2019. “Architecture is not just a finished product or a standalone object,” she said. “We think about it more as a process for connecting people to their environment.” The days of constructing buildings for their own sake is long over. They need to become part of ecological landscapes, in which humans can feel more connected, and birds, bats and honeybees are not threatened in urban environments. Her vision of ‘actionable idealism’ sees her Studio Gang take on a variety of multidisciplinary projects that may not even involve buildings – provided they serve the greater good of communities (like social justice projects) and landscapes (like renewing Chicago’s waterways). “Architecture should improve relationships for people,” she said. She also asked how communities can remake public spaces with complex histories, and repurpose a hurtful and damaging past into something that can leave a legacy of ethical probity. A fitting way to conclude a conference that emphasised connection, empathy and human rights over the soulless use of technology and the rise of demagoguery in the world today.

A fitting end to the three days of inspiration, ideas and innovation was the announcement of the winner of the Department of Audacious Projects Design Indaba 2020 challenge, Farayi Kamabarami. His winning idea 'Ubuntu Shrine: An ode to being Human', envisions an agnostic shrine being built at the Cradle of Humankind. A shrine that will become a non denominational pilgrimage for tourists to reconnect with their common humanity - a place to rediscover and experience the spirit of Ubuntu 'I am because you are' and our interconnectivity. Kambarami's idea won him R50 000 throught the first in a series of challenges that aim to solve for tourism in South Africa.