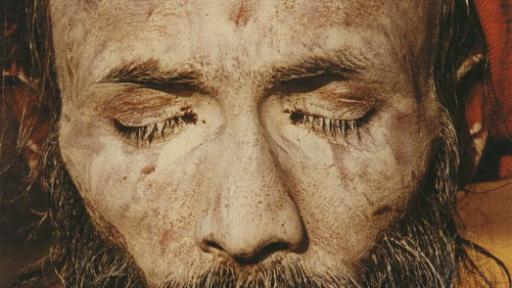

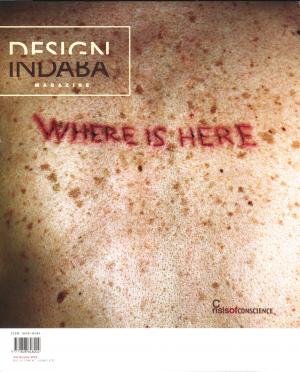

Crisis of conscience

I have wandered many places in search of an answer. Wondered a lot. But let me stop here, start things rather with a question. Why have I themed this issue “Crisis of Conscience”? Why not simply “Crisis”? After all the word singularly encapsulates all the uncertainty of our times.

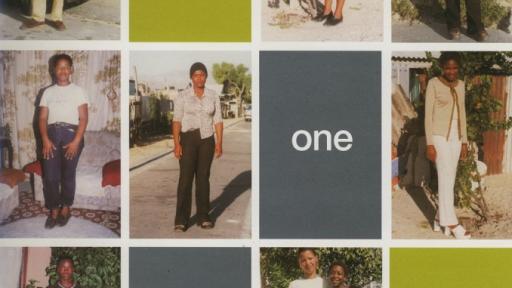

I could simply state that Ravi, the magazine’s publisher, suggested the issue be themed conscience; that crisis of conscience, uncertainty, describes a median compromise between our two visions. But there’s actually more to it than that. A lot more. Our planet is in a state of crisis, both environmentally and mentally. I believe this unequivocally. But, like Ravi, I am also an optimist. Despite having seen the urban squalor of Langa, the disgraced ghettoes of south London, Japan’s concrete catastrophe, even the nervous decay of my youthful suburban neighbourhood in Pretoria, I remain optimistic.

Optimistic because its opposite is unworkable: It is very easy to simply let things slide from pessimism into nihilism. (Hell is a ghetto filled with nihilists.)

This issue of Design Indaba addresses two key concerns. The first is the upcoming World Summit on Sustainable Development. Having emerged from centuries of darkness, South Africa, Johannesburg will host a forum designed to assess how best we can chart current developmental needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This, after all, is the simplest expression of the issues facing delegates at the Summit, and one this magazine has sought to address through the simplest of structures, the house.

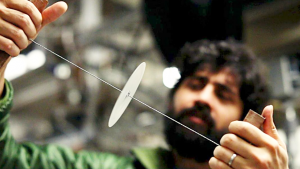

But this is a design magazine. What, you ask, do poverty and a dwindling supply of water have to do with design? Again, I answer with the words “a lot”. Neville Brody previously hinted at it, asking the simple question “Can Design Feed People?” It is a serious question, one I have chosen to phrase slightly differently in an issue that explores the ethics of design. That question: Is design vested with a conscience?

As the collective work of the designers Jonathan Barnbrook, Fernando Gutierrez and Stefan Sagmeister reveals, the answer is undeniably yes. In Jonathan’s case, he even signed a polemical design manifesto challenging the design community to focus its immense problem-solving skills on unprecedented global environmental, social and cultural crises. If I can make only one request, it is that you pause on these three designers’ work. Their work demonstrates that, despite its tarnished reputation, the design profession can be a corrosive force against amnesia.

This same observation applies to all the talented visual communicators profiled in this issue. Their work may ground us in these dark times, but somehow the ideas they put forth also point us to the light. After all, we are optimists. Which brings me back to my opening statement. I have pondered upon this issue, wandered around my own head in wonderment. Nerves. Uncertainty. Will readers share in my enthusiasm for the topic? Paging through the tatty notebook that accompanied me along my wandering path, I encountered this personal note: “Be angry! Be thoughtful! Be Serious! Irony is worse than indifference.”

It is my sincere hope that this issue of Design Indaba magazine proves that design is not just about post-modern cool and ironic disaffection. It is about love, humanity and communality – and the urgent need to sustain all these things. – Sean O’Toole