First Published in

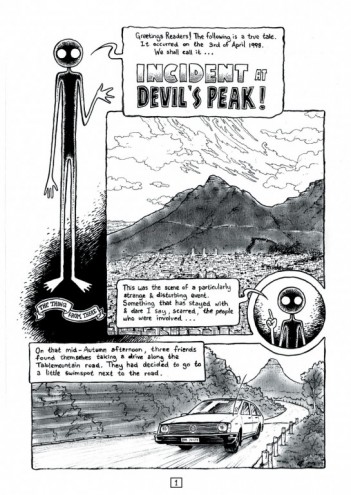

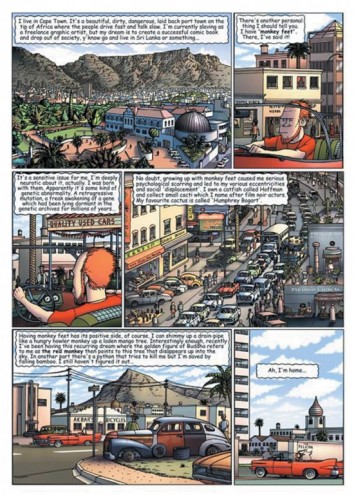

No country proves that comics are an extension and expression of a nation's psyche more than South Africa. Historically, local comics have never been able to move out of the shadow of national events and the cultural stresses that form our country. Politics, sport and societal concerns dominate our society and this is reflected in the comics South Africans create and identify with.

Comics have been used to entertain, inspire, uplift, satirise, popularise and propagandise certain viewpoints. The medium is perfect for bringing the artist's or writer's message across to the reader - whether or not the reader is from the same country, or has the same beliefs, education or values. The work of Zapiro, Rico and Bitterkomix is totally dependent on a need to analyse, comment and engineer a change in perception of society. As with our other literary works, this is the product that has found the broadest appeal with local readers. The most celebrated writers create stories that pertain to a South African mindset and draw on our culture which, in itself, is not a bad thing. Though JM Coetzee, Andre Brink and others are talented, award-winning writers, their work suffers from the inability to break away and be fiction for its own sake. Not surprisingly, South African comics have also 'evolved' to art with a message, instead of being what it should be: entertainment.

South African readers quite easily shoehorn comics into two categories: kiddie comics and intellectual cartoons. Highbrow political cartoons are intellectually acceptable precisely because of their commentary and specific viewpoint, while superheroes, manga and European imports are perceived as a childish pastime. At the same time, local retailers, quite literally, put comics out of the reach of this supposed youth market: both in terms of pricing and also in terms of rack space. Comics have become such a luxury item that the average person can't afford them. Coupled with this is the literacy problem experienced in the country, and the competition from other forms of entertainment. Movies offer consumers a product that requires less effort and imagination, and electronic gaming allows a level of interaction and action impossible to replicate in other media.

Madam and Eve is arguably South Africa's best-known longest-running cartoon series. But its success depends on the writer's ability to tap into, and put a twist on, local concerns and views. While this, and the work of Bitterkomix, has found limited success internationally, it still has not broken the mould in creating something with universal appeal. Nor is it likely to if the focus remains on expressing a specific political viewpoint.

The write stuff

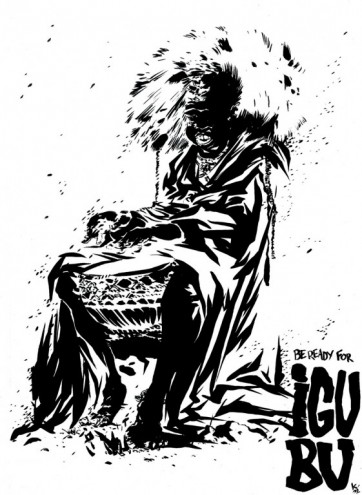

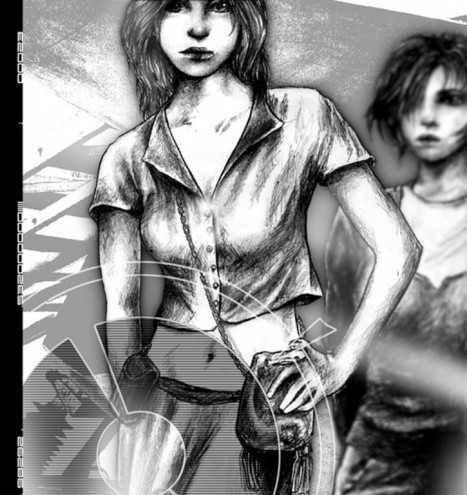

The Japanese did it. They created a whole way of life around comics after World War II. And they did it without slavishly following the superhero trend as done in the West. South Africa can as well, if it focusses on good storytelling. Manga (Japanese Manga) is anything from westerns, horror and legends. Using what we have locally is the best way to attack the market, both here and abroad. Our different cultures are the perfect source of legends and heroes. Who needs Superman or Batman when you can tell the story of Nelson Mandela's "Long Walk to Freedom" in the comic format? Yet it is merely a question of finding a concept as sound as that, of some legendary, historical or iconoclastic figure and drawing the story of that figure's life. In other words, fiction based on fact. Fictional characters, if properly conceptualised, can take on a larger-than-life status. The only way to create storylines and characters that people can relate to, is to be as real and true to reality as possible throughout. Even if your lead character is a superhero or a god, he occasionally will have his human moments. All great stories eventually teach us something about the human condition, will, or psyche, but this does not mean that one should agonise over every last panel or scene, thereby losing the essence of sequential storytelling.

Influence of international comics

To understand comics in South Africa one has to look at the influences on our own home grown product, such as our own history and the influx of comics from other countries.

In most countries, comics have become an integral part of the culture of the people of that country. In the USA comics helps define the way that the nation perceives itself - 90% of the comic market is superheroes. Americans created characters like Superman and Captain America to be heroic symbols of truth, justice and democracy, much as they want their country to be seen. At the same time characters like Spiderman, Batman and the X-Men represent the darker, rebellious side of their populace. These creations have enormous international appeal. The theme of heroes is popular, no matter what guise the hero takes. And in the case of South Africa, the comment is often made that we strive to be more American than the Americans.

While superhero comics sell in Europe, the Europeans have built their own comic industry, which is a lot more diverse and mature. International European exports include Prince Valiant, Tintin, Lucky Luke, Judge Dredd and Diabolique - characters that are more fully-realised and realistic than their American counterparts. And they too have enormous appeal internationally with their realistic settings, fast-paced stories and humorous situations. South Africans respond to these comics because more often than not, the writing is better than the formulaic approach taken by American comics.

The last market is Japan. Though this is the newest influence on South African comics, there is no disputing that manga (Japanese comic art) has already spawned a young generation of hip-hop artists here.

Manga covers all genres: sci-fi, romance, historical, erotic, supernatural and superheroes, and all these topics are tackled from a uniquely Japanese perspective. South Africa has mostly only been exposed to the child/teen product - Pokémon, DragonBallZ and Digimon are recent high-profile exports. But there is no denying the influence of groundbreaking work like Ghost in a Shell, Akira, Battle Angel Alita and Ninja Scrolls internationally. These four books revolutionised comic books and established the Japanese manga as one of the most exciting and innovative industries in the world.

Creating a comic book culture

So how does one create a lucrative local industry in view of the challenges that currently exist? The biggest deterrents are lack of distribution infrastructure, financing, the average person's perception and the fact that we have a new generation of non-reading, television-focused consumers.

South African comics will remain a sub-culture, underground phenomenon unless all players combine their efforts to change popular perception. To get comics into the mainstream, creators have to research how relevant their stories and art are. While art and writing is always about expressing oneself, too often one tends to fall into the trap of becoming repetitive.

We must question WHY certain forms of popular entertainment have become such a huge part of our local culture. Afternoon soap operas are hardly the most creative, best-written or best-acted series made, but despite this they have built a huge viewership in a relatively short time. The same can be said for reality television or pseudo-realistic movies such as the Blair Witch Project. It seems certain things within this formula appeal to viewers. Even though most South Africans will never experience the exciting lifestyles or be confronted with the moral choices made by the movie characters, the viewers are fascinated by them. This glimpse into the lives of the rich and famous has become a national obsession. The top-selling local magazines invariably pander to this voyeuristic compulsion, but does this mean that South Africans can only identify with characters or their real-life counterparts? Does the public have the imagination to appreciate comic books? Undoubtedly. So, it seems then that the problem is one of perception.

While it is totally acceptable for grown people to gossip about cardboard actors, it is less acceptable to discuss, or even acknowledge, comics. Comics are for kids and let's forget that some of the biggest box-office hits over the past few years had their start in comics. Men in Black, The Matrix, Blade, X-Men and Spiderman all had their origin there. But how many people know that From Hell and Road to Perdition were comics first? So does the 'comics are for kids" argument hold water? Obviously not.

Telling great, innovative tales with realistic characters in an exciting setting is not enough. Comics also need to be equally accessible in Sandton, Mitchell's Plain, Chatsworth or Soekmekaar. Some inroads have been made in reaching the masses by projects such as the Supastrikas comic currently running in national newspapers. A brilliant concept supported by financing from South African business, plugged into an already existing base. The companies that sponsor it get their advertising on almost every panel, the newspaper attracts the youth market and the artist and writers get the exposure and experience they need.

Our government has other, more pressing concerns, but without their financial support, creating a vibrant comics industry locally is a serious uphill battle. By sponsoring competitions, exhibitions and comic conventions they can raise the level of awareness of the South African public. Currently more support is being shown by foreign governments for art projects. Most notably the Swiss Pro Helvetia Office and the French government recently organised the Comics Galore festival nationwide. In aid of this they flew international artists to South Africa as well as organising lectures at UCT and Stellenbosch, and a convention in Johannesburg with Bitterkomix. The Festival of International Comic Art is a 6-month programme of events including exhibitions, an international conference, workshops, lectures and book launches dedicated to Comic Art in South Africa. The exhibition started in Johannesburg in November, moves to Cape Town (Bell-Roberts Gallery, 18 December - 18 January 2003) and then to Durban (Natal Society of Arts 28 January - 16 February 2003). The Comics Galore festival is intended to become an annual event.

South Africa is totally different from other markets. South African comic creators need to realise that in the interest of a vibrant comic culture, national collaboration between groups like Durban Cartoon Project, Bitterkomix and Igubu is essential. By having a focused national group pooling resources our industry will take off.