First Published in

Who is your audience, who do you hope to reach with AFRO?

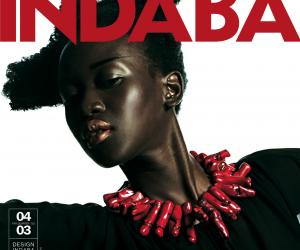

We’ve tried to use design to entice young people in particular, to get them to read something that they otherwise wouldn’t read, to provide a platform from which they can interconnect with one another and learn about what other young people in Africa are doing with their lives. We saw AFRO as an opportunity to combine social and artistic objectives with a personal endeavour.

To what extent is AFRO about identity? Would it be fair to say that it represents a personal struggle to construct an identity beyond the two-dimensionality of white guilt?

“I’m not European and I’m not African, I’m speaking a language that was born here and I have no where else to go. But I’m not really concerned with identity as such and I’m tired of the debates about who can represent whom, I think that one must just attempt to contribute in spite of colour.”

What are you trying to contribute?

Well, I’m not trying to define an Africa design aesthetic. But I do think it’s important that what you do be informed by your context. I work from Cape Town and it bothers me when people here say, "let’s go to Africa". It’s as if half of us are in denial about the fact that we are part of this continent and the rest of us have a kind of naïve or romantic attachment to it.

In one of AFRO’s short stories, Disgrace, Stacy Hardy subverts the particularities of Western naivety by artfully exposing the ways in which Western discussions of race become preoccupied with oversimplified concerns for positive and negative portrayals; and how discussions of sex inevitably, relentlessly, become politically correct dialogues about sexual identity.

So, this is about using design to raise awareness.

I do think it’s more important for people to know about what is going on here than what’s going on in David Beckham’s life. And I know changing what the media feeds us is nearly impossible, but again, I’m focused on what I can contribute, on how I can use my creative energy to design something with a social conscience.

How do you balance that social conscience with the world of international design?

What is being called international design is really mostly based in the US and the UK and I think it’s important to break away from that. We don’t have a history of minimalism or modernism as it exists in the West. Yes, historically we’ve lacked the resources to cultivate a contemporary urban design language of our own, but today that can’t be used as an excuse to do bad versions of what is happening overseas. I don’t care if AFRO is not seen as international design. There is really no reason to continue to measure ourselves against the West. So, I’ve mostly stopped looking at design annuals from overseas. I’m rather looking at contemporary art, films, fabric, photography and music from Africa. I also think it’s important to be actively involved in contemporary art, film and theatre. Rather than looking at the surface and going off of what you think is going on in those fields, you can make yourself a part of the dialogues that are actually happening.

A kind of cross-fertilisation?

Yes. And working on AFRO has been important to my commercial work as well. It not only informs my commercial work, it’s a way of creating a bank of unique imagery - and this way, you don’t have to worry about stealing, you know it’s yours. As designers we have arrived at a place in which we must confront our power, our responsibility; begin to use our creativity and our knowledge of markets to find new ways of negotiating the increasingly influential world of images.