Photography has transformed radically since the art went digital, this we all know. Lesser known is how this has affected professional photographers’ relationship to their work. Where does the photographer’s creativity begin and end? What is the relationship between any artist and the materials of their craft? And what does the physical nature of the photographic print mean to the art of photography?

It’s not a black and white scenario (no pun intended), as there are distinct advantages of digital. This is all apparent in New York City photographer and film director Harvey Wang’s new book, From Darkroom to Daylight (Daylight Books, May 2015). It has also been made into a documentary currently screening at festivals across the US.

Wang is widely published, with five books under his belt, including the critically acclaimed Harvey Wang’s New York and Flophouse: Life on the Bowery. His latest book includes interviews and photographs of more than 40 important photographers and prominent figures in the field, including David Goldblatt, Gregory Crewdson and Sally Mann.

Here he tells us why he embarked on the project and shares extracts of four interviews from the book.

I began taking pictures for real at the end of middle school in the early 1970s. It was unusual to walk around with a camera in the Queens, New York neighbourhood where I lived, but from age 15, I was never without my Nikon camera. I would shoot black-and-white film and develop it in the basement darkroom of my house.

I loved the ritual of developing film and making prints: removing the exposed film from its metal canister, spooling the film onto reels in darkness, measuring the chemistry, and pouring each chemical into the developing tank.

After the film was in the fixer, I could open the tank and see the negative images on the film for the first time. When the film was dry, I’d cut the negatives into strips and make a contact sheet. The negatives were placed in an envelope, and a number was assigned to each envelope. The same number would be put on the corresponding contact sheet, and they were stored in boxes.

Every year, a new box was added, and the contact sheets became a diary visually documenting my passage through the years.

For over 25 years, I exposed black-and-white film, developed it, and made contact sheets and prints. I stopped adding to this multi-decade collection of sequential envelopes in about 2000, when I started to shoot more colour, and eventually to shoot digital.

Some time later, I realised something had changed about my relationship to photography. I wasn’t sure that the new ways of working suited me.

I wondered if other photographers’ worlds were turned upside down when they stopped mixing chemicals and isolating themselves in the dark.

That’s when I started the project From Darkroom to Daylight. In 2008 I began interviewing photographers to see how the dramatic change from film to digital had affected them and their work. I also spoke with people in industry, conservation, and education, as well as Steven Sasson, co-inventor of the digital camera, and Thomas Knoll, co-creator of Photoshop.

Below are some of the voices from the project:

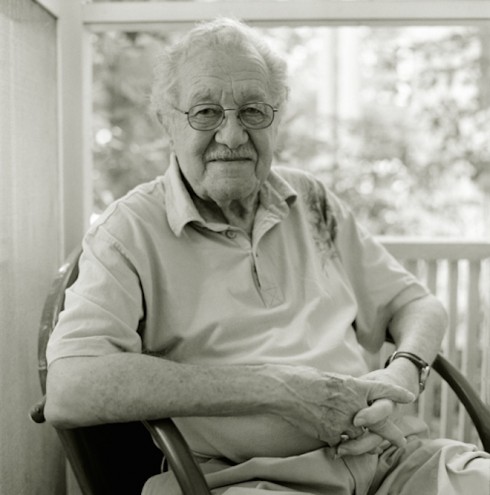

Jerome Liebling (1924-2011)

Photographer, photo league and distinguished educator

Interviewed 11 August, 2009, at his home in Amherst, Massachusetts

The computer is here. It is here. And how deeply it’s here, and how it’s changing the facts of life is what you’re searching for. People say, “Hey, Jerry, hold still,” and they take out the telephone and they take a little picture. I don’t know where it goes or what happens to it. I think within photography, the cusp is over. The daguerreotype is dead, the dry plate is dead.

Can you go back and make a dry plate? Yeah. A wet plate, or whatever they call them, an ambrotype? Yes. But so what?

If I walk through the streets with my Rollei, people say, “Oh, is that a new camera?” I think the scariest term was when somebody said, “Oh, Jerry, you still practise alternative processes.” That the negative, and film, is an alternative process? It’s not a frontline process! That hurt. [laughs]

The thing that I object to with digital is Photoshop. I think if you want to make pictures, you want to be a painter… well that’s fine, go ahead and do it, but don’t call it photography. Photography meant there was a response to the fact of life. [With Photoshop] what you’re saying is, I don’t really need the world; I can make the world. And artists, painters, have been doing that for many, many years. But then I go back to that essence that I thought photography as mirror image was very important and special.

Sally Mann

Photographer

Interviewed 23 November, 2012, at her home and studio in Lexington, Virginia

You pick your materials to suit your aesthetic and your vision. Sometimes it’s the other way around. Sometimes the process informs you what your vision really wants to be. I’ve had moments where I didn’t know what I was doing, but the film showed me, or the material showed me.

There is something about this (wet plate) process that’s a little more contemplative. And also, here’s another thing about these long exposures, something goes on with the eyes. There’s a certain sadness and depth that’s revealed in someone’s face, I think. You know you’re sort of sitting for the ages, and I don’t think an iPhone picture makes people think that they’re sitting for the ages.

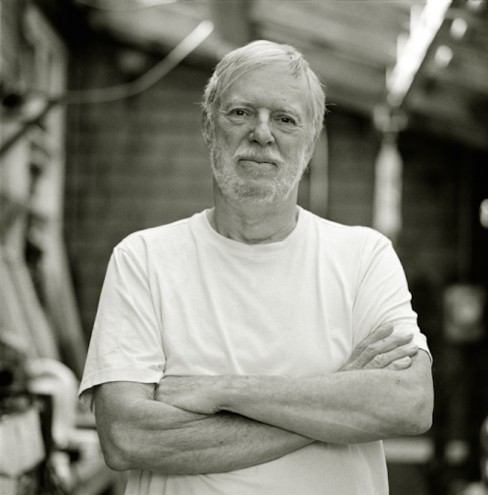

Paul Messier

Photograph conservator

Interviewed 27 April, 2011, at his conservation studio in Boston, Massachusetts

In 100 years, what will persist, a digital file or a silver-based photograph or negative? I think, all things being equal, it’s the silver-based photograph. I don’t think it’s much of a contest. There’s just too much that can go wrong with the digital file. First, it’s machine-readable.

I mean, as long as human beings have eyes and the sensory equipment associated with the brain, they’ll be able to look at a photograph, interpret a photograph.

A file, if it exists, is a series of bits, and you’re going to need some sort of machine to read it. Not only that, you’re going to need a machine that has the capabilities to accept whatever media the thing is saved on. Will there be USB thumb drives in 100 years? Or computers that will be able to use hard drives made in 2011? No, there won’t. You would need to assume some sort of very active migration process to keep those files alive.

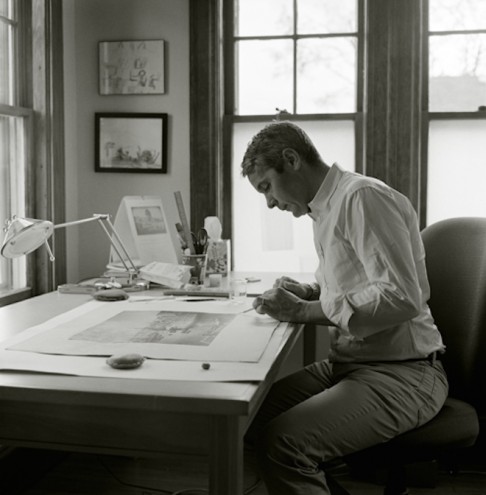

Richard Benson

Master printer, photographer, distinguished educator

Interviewed 5 October, 2012, at his home and studio in Newport, Rhode Island

Silver is basically dead, and by God, it should be. It’s overdue. It was great while we had it. I think the digital capture is far superior on every level… I certainly have times where I wish the whole electronic thing would just go away, and I think the reason I’d like it to go away is that I remain enthralled with the physical object that is made without benefit of electronic technology, but as a photographer, nothing compares with what the digital media will give me. And so I have to put up with that goddamn stuff.

“From Darkroom to Daylight” is available to purchase on Amazon. Signed copies of the book are available here.