Tiffany Chu was one of MIT’s student envoy sent to help with relief efforts in New Orleans after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. “I was a fresh, bushy-eyed student. It was basically one of my first jobs,” she said.

The experience was transformative but not in the grad student-saves-the-poor kind of way. “I saw that there were these students being parachuted down from a different part of the world and expected to make some sort of impact in three months. Three months is only a blip of time when you consider it against the past 10 years that New Orleans has been recovering from the disaster.

“If you’re trying to help a city, you need people who are from there and who are invested in the city over time – and there are [people like that], I was just not one of them.”

Chu spoke at the inaugural Design Commons, which took place in Helsinki this year.

This realisation would form the foundation of her work in the tech industry. Remix, the four-year-old start-up she co-founded with Sam Hashemi, is redesigning the way cities and city planners design their transit routes by making the design process accessible where it had for decades been complex and driven by labour intensive processes.

If a city planner were to try and do something as simple as shifting a bus route, they would have to use hand-drawn routes and spreadsheets to manually evaluate factors such as the cost, the impact on the environment and the impact on other transit routes to name a few. With Remix, planners are able to plan and test complex scenarios in seconds. It also gamifies the process, making it easier for policy-makers or other stakeholders to comprehend and hopefully invest some money.

Remix was named a GovTech 100 company for 2017 and recently raised $10 million in Series A funding. This comes after the web-based platform tripled its profits in 2016. Over 200 cities in over 10 countries now use Remix, and the company has helped approximately a quarter of all US transit systems optimise transit routes, impacting close to one billion transit trips per year.

When I ask Chu if she’s surprised, she answers that it’s more like bewilderment. The project started as a side project between a group of four technologists – Chu and Hashemi included. The initial platform allowed residents from San Francisco to suggest new bus routes using a drag-and-drop function. Called Transitmix at the time, the programme went viral overnight, attracting over 250 planners looking to have a similar system established in their cities.

In 2014, Chu and Hashemi founded the company based on the Transitmix prototype and now they are known to have taken transit planning into the future. But for Chu, the process would not be a success without an equal investment in the people in the cities it serves.

“We develop long-term relationships with our cities who are Remix customers. We’ll start off by visiting the city. We spend a couple of days on-site helping them train, and really understanding their context,” she explained. “We don’t do short-term or couple of month projects, we say we want to be your resource for the next three to five to seven to ten years.”

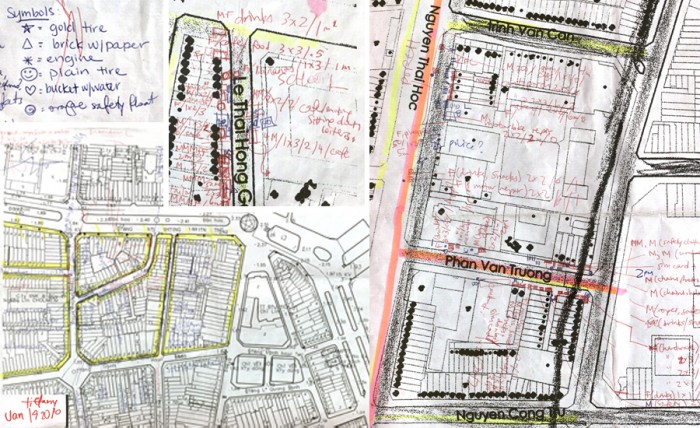

This investment in the community was something she picked up in an earlier project. As part of her graduate thesis at MIT, Chu travelled to Vietnam to map 1000+ street vendors in Saigon. There, she worked to affect change at a policy level by talking to the people of the city about the importance of street vendors. She tells me that the experience taught her that her work, whether in architecture or tech, is essentially about people rather than design.

“I guess it’s bringing information to people where they are and making it more accessible in a way that’s understandable to everyone and not just the academics that you think might be reading your research. So, that was what I learned in Vietnam,” she says. “In my day to day, right now, that’s basically what I do. It’s basically taking complex topics such as how transportation works in a city and boiling it down to, you know, the one or two high-level takeaways that make a policymaker say, ‘yes, I understand now and I want to make this change as a result.’”

It’s no surprise that Chu brings up policy so frequently during our talk. Change is unlikely to happen in a city when local governments are ineffective or if local governments are not supported by national funding. That’s the situation in the United States right now, explained Chu. As the Donald Trump administration leans to more conservative, more budget-cutting views with regards to public service, plans to build new infrastructure in the country’s cities is faltering.

“A city might have already invested in the planning stages of a very large infrastructure project such as a Bus Rapid Transit route. It requires a lot of community by in from stakeholders and the moment that you introduce a tiny bit of doubt, for example, the doubt that federal funding may or may not come through, then it throws the entire project into risk,” she said. “It throws that local government into disarray where they don’t know whether to continue spending resources there or whether they should be spending their money elsewhere.”

Along with the federal government, people on the ground can also push back against proposed changes to infrastructure. According to Chu, what’s playing out in cities today is a battle between the haves and the have-nots, the latter of which often finds themselves farther away from the opportunities such as jobs and education.

“To be honest, I think it’s a battle for space,” she explained. “That battle can be seen everywhere, from the battle for housing affordability in many of the top expensive cities in the world, and it’s also a battle of accessibility for neighbourhoods trying to connect themselves to the rest of the city. That’s usually done through some sort of transit or transportation. So this issue of space and who gets what space and who is allowed to prioritise their space over others.”

While conservative notions tend to exclude and other minority communities or vulnerable groups, Chu believes the conversation needs to centre the benefits of a truly diverse, mixed-use city.

“A lot of the voices in the conversation are very selfish in the way that their cities are planned because everyone wants to protect their own property values. People think buses are for poor people so they don’t want buses going by next to their house because it’s noisy and we need to have a conversation around how do we make the city better as a whole, for everybody instead of just for specific groups of privileged people.”

For now, Chu plans to use Remix to make it easier for changemakers to attract the funding they need to help their communities. She’s like a designer working to make better design possible.

“So it’s helping the practitioners, who are the ones doing all the work, and saying, ‘Hey we want to help you visually communicate to convince the city council or the board of directors to get more local funding for your projects instead of depending on other more risky sources.’”