1. Es Devlin’s ZOETROPE

Our whistle-stop tour through six of the most extraordinary pavilions in the world, as conceptualised by Design Indaba Alumni, commences with large-scale artist Es Devlin’s 2019 ZOETROPE, which provides a glimpse into the future of electric travel.

Commissioned by emission-free motoring pioneer, Mercedes-Benz, Devlin’s interactive installation on Silo Square at Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront employed green thinking to show the potential for a solar-powered network of pavilions – each one acting as a charging station for the mind of the driver. Mirroring a physical and cultural journey through the built environment of the city of Cape Town, visitors walked through a maze spanning the length of 12 short educational films.

This ground-breaking installation fostered an appreciaton for the relational symbiosis between solar energy, location and electric mobility, making use of an impressive merger of light, colour and sound. Over and above the way in which it introduced Electric Inelligence (EQ) technologies to the South African public, it also showcased how the automotive industry can shape the future in fascinating yet sustainable ways.

2. Francis Kéré’s 2017 Serpentine Pavilion

The 2017 Serpentine Pavilion in London’s Hyde Park was a UK debut for Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning, Burkina Faso-born architect Francis Kéré.

Responding to an invitation from the Serpentine Galleries, which is extended each year to an international architect who has not yet built a structure in London, Kéré’s tree-inspired pavilion featured a steel-roof canopy with a transparent skin cover. This meant sunlight could filter through for those within, yet rainwater would be kept out.

Known for his socially engaging and ecologically sensitive approach, Kéré drew inspiration from the tree that serves as a meeting spot in his hometown of Gando. The nature of his creation meant visitors could enjoy a sense of connection, not only to each other, but also to nature itself. Wooden shading inside the roof formed a dynamic shadow effect, similar to the shade of a tree, fostering a sense of protection. The architect was praised for the way in which he embraced the British climate, as well as for the series of talks he gave at the venue, which explored questions of community within a big city.

3. Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion II

Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion II is a structure impossible to label because of its unique interface of biology, technology and engineering.

Standing 6m tall and 5m wide, the Silk Pavilion combined the built with the grown. The structure was built by 17 532 silkworms, but guided by Oxman’s team at Mediated Matter Group.

How can knitting, making and building become truly sustainable in an age of human impact on the Earth? How can human beings and animals join forces for their mutual betterment? This pavilion offered many insights – like influencing silkworms to spin in sheets, not cocoons, so the larvae are not affected in the process. “[My team] loves this idea of using a single material as a sysem to enable strength and tension, depending on where these properties are needed,” said the artist at the time.

This project stands out for its cross-species collaboration, in which a braided steel structure guides the silkworms’ handiwork, and for the way in which we should look towards age-old natural processes when contemplating new-age design.

4. Shigeru Ban’s Japan Pavilionat the EXPO 2000 in Hannover

This Hannover EXPO pavilion focused primarily on the built environment. The underlying concept involved producing the least industrial waste possible when dismantled, so all materials had to be reusable or recyclable. Construction was not without challenges – like replacing the engineer, construction delays, and the addition of a fire-safety PVC membrane – but there is no disputing how Ban’s paper architecture advanced via this creation.

Paper tubes were used on the tunnel arch, but, due to the high cost of wooden joints and the issue of lateral strain, the artist suggested a grid shell composed of three-dimensional curved lines with measured indentations in the height and width. Joints were of fabric or metal tape; foundations of a steel structure; and a fixed timber frame was added to strengthen the grid shell. PVC, originally used in the membrance, gives off dioxins when burnt, so this was replaced. Instead of relying on concrete, Ban ensured that the foundation was made of steel-framed boxes and footing boards filled with sand for easy dismantling later. Ban soared here by creating the world’s biggest and most repurpose-able cardboard structure.

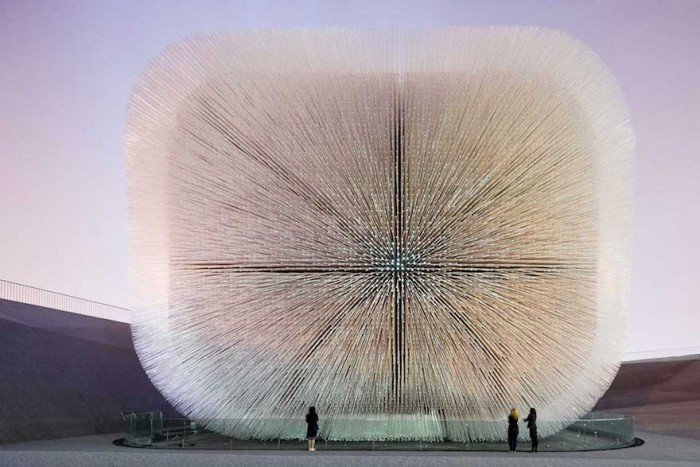

5. Thomas Heatherwick’s UK Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo

The penultimate stop on our tour takes in the UK Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo, brainchild of British designer Thomas Heatherwick, who leads Heatherwick Studio.

What is astonishing about this 2010 project is the architecturally iconic seedbank, Seed Cathedral, positioned at the centre of the pavilion. Standing 20m high, it consisted of 60 000 transparent fibre-optic rods – each slender rod 7.5m long and encasing one or more seeds at its lip.

In exploring the theme ‘Better City, Better Life’, the rods drew daylight into the cathedral’s interior; while inner-rod light sources created a glow across the entire structure at night. Visitors described it as “a sight to behold…quiet, tranquil and environmentally friendly”.

These are the sort of astutely conceived spaces we need in big, bustling cities – places where we can experience nature, as was the case when the wind moved with a soothing sound through the seedbank’s fibre-optic ‘hairs’. In London, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew is the site of the world’s first public park and major botanical institute, and it is apt that Heatherwick Studio brought Kew’s Milennium Seedbank to the Expo, with the goal of collecting the seeds of at least 25% of the world’s plant species in a defined space of time.

6. Sir David Adjaye’s 2019 Ghana Pavilion

The Ghana Pavilion, entitled ‘Ghana Freedom’, was hosted at the 2019 Venice Art Biennale and celebrated the country’s six decades of independence from colonial rule.

This elliptically shaped exhibit, which explored an intersection of diaspora-related ideas from six Ghanian artists – Ibrahim Mahama, El Anatsui, Felicia Abban, John Akomfrah, Selasi Awusi Sosu and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – was designed by Adjaye and curated by art historian/filmmaker Nana Oforiatta Ayim.

With a nod to the interlinked notions of geography, culture and place, the designer’s firm strives to create architecture that responds to a changing world, the needs of the public, and how the act of making may influence the people who will eventually inhabit a space. Adjaye refers to it as “responsive architecture … I want to move away from South African or Ghanaian architecture to forest, mountain and desert architecture”. As natural disasters erupt around us, his thinking is that geographically relevant architecture should be able to respond to and offer protection against an increasingly fragile ecology.

The question is: what makes a perfect pavilion? We challenge all you designers out there to come up with a concept for the quintessential South African pavilion. Share your ideas for making the Expo world better through creativity!

Read more:

#DI Alumnus Snøhetta takes green building one step further by developing sustainable concrete.

The future of green design.

Recycling the Serpentine Pavilion.

Credits: Heatherwick Studio, Iwan Baan and Karl Rogers