Graphic design student Sara Jamshidi is using postage stamps to focus attention on the history of Iran.

Her postage stamps, Project M, tell the stories of people and events that government officials have suppressed. It forms part of a series of proposed stamps that could be used alongside the already existing Iranian government stamps.

For people in Iran, postage stamps are a reminder of the control the government has over their identity, their culture and the interpretation of their history. Jamshidi’s collection is her way of pushing back.

A number of protests have occurred in various cities throughout Iran beginning in December 2017 and continuing into September 2018. Many of the protests have called for the current government to be overthrown.

After studying graphic design at the Royal College of Art in London and then later, moving to the United States, Jamshidi, who was born in Iran, still has close ties with the country and hopes to bring its rich history to light.

The current postage stamps used in Iran symbolise the country after its 1979 Islamic revolution. After it overthrew the Persian monarchy, Iran became an authoritarian country with an uncompromising version of Islam at its core.

But there is more to the country than its post-revolution history. Jamshidi explains, “For Iranians who left their homes during the 1979 Islamic revolution and couldn’t go back, the stamps on the letters they received from their families in Iran became a window to the life in Iran.

“I became interested in the narratives and history that exist between the stories shown on the stamps.”

The ‘M’ in her project title stands for From Monarchies and Mullahs to Mardom and it features past Iranian leaders and activists.

“What motivated me was asking myself: If I had a chance to throw a new light on history, would I take it?” she says.

The stamps have featured people such as Kavous Seyed-Emami, an Iranian-Canadian professor and environmentalist, who was detained by Iranian intelligence agents, and who then died in prison at the age of 64.

According to Jamshidi, his death was ruled a suicide by Iranian officials, but to this day they have refused permission for an independent autopsy.

“Seyed-Emami’s stamp has the number 64 on it. One of my main reasons for not having his face on the stamp was that I had to consider the safety of the recipients of the postcards in Iran that has that stamp on it,” she explains.

Another series focused on Iranian women and their campaign against wearing the hijab (Islamic headscarf). The stamp showcased drawings done by renowned Iranian cartoonist, Mana Neyestani, who has become an icon in the movement.

“I am proud to make stamps that embrace an icon of Iranian women fighting for their right for freedom from the hijab. I consider it my small contribution to this important cause,” says Jamshidi.

Like Seyed-Emami’s stamp, the entire collection proved to be delicate and thoughtful work. Jamshidi says it was important that she individualise each stamp according to the era in which they belonged. She did this through colour, typography and symbolism.

“Stamps of each era required a different approach: the stamps after the revolution I studied chronologically and looked at the number of stamps printed during the reign of each cabinet. I also looked at what their main policies were with regards to the socio-political situation of the time,” she explains.

Despite her efforts, her stamps may not be used at all. Jamshidi explains that she tried sending cards to Iran to showcase the postage stamps but, unfortunately, the Iranian government confiscated them.

“Since I have sent the cards to Iran, and considering the political nature of some of the stamps until now, I have refrained from publicising the project, in order to not cause any sort of danger to the recipients of the cards,” she reveals.

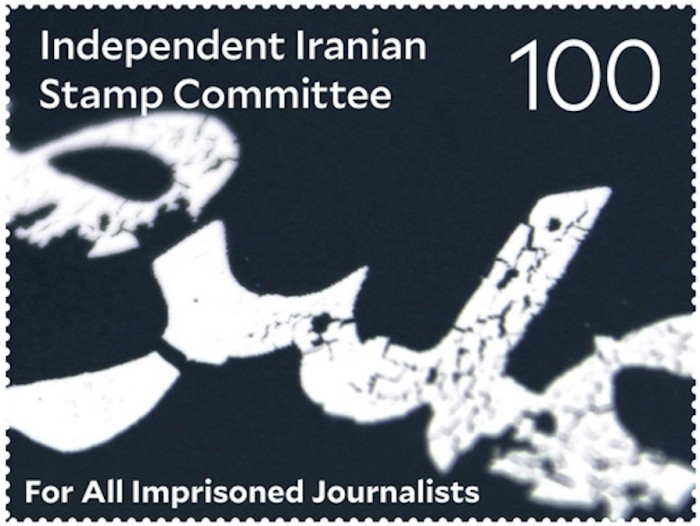

Jamshidi has since started the Independent Iranian Stamp Committee, where she invites Iranian people from all around the world to tell their stories.

More on art as a form of protest

Edel Rodriguez on childhood, nationalism and a nation on fire

From dreaming up stories to starting a movement with the multi-talented Buhle Ngaba

Cole Ndelu explores the dissonance of masculine femininity in her new photo series