While the definition of what constitutes a ‘smart city’ may differ, it's agreed that in order to be considered a smart city, a place would need to employ digital technology to improve services such as city planning, provision of municipal services and more.

Over the past few years, plans have been afoot in a number of African countries to develop their own smart cities. For example, Nigeria has Eko Atlantic (above) while Ghana has Hope City (below).

Eko Atlantic in Lagos is built on land reclaimed from the sea and it is estimated that it will house about 250 000 people once it is completed. Hope City, which is yet to get off the ground, will feature the continent's tallest skyscraper.

But the big question remains as to what happens to the cities that currently exist in these countries, and where will African residents who cannot afford to move to these new smart cities go?

These questions have been top of mind for Togo-based architect and anthropologist Sénamé Koffi Agbodjinou. He made the 2019 list of African Innovators and was recently part of a panel discussion on Digitizing Africa that was put together by the Design Indaba team during the N'GOLÁ Biennial. In his hometown of Lomé, the capital city of Togo with a population of just over 830 000 people, he has been working on building a different kind of "smart city".

To him a smart African city is about more than images of tall buildings.

“You can have a very old city that is smart just because a lot of little technology. Those people who are talking about smart cities in Africa should show us the technology they want to implement in the city to make it smart. What I also say is that if it is an African smart city project, you have to make the effort to use technology developed in Africa,” he says.

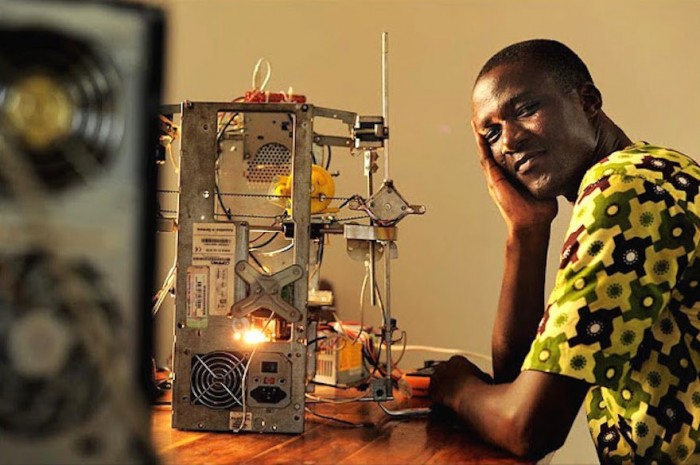

He has been testing this approach over the past few years through the work he does at L’Africaine d’architecture, a collaborative research platform that consists of a website as well as a grassroots incubator, WoeLab, where Africa's first 3D printer was invented by Afate Gnikou Kodjo.

Kodjo's 3D-printer was made from scrap material at WoeLab.

Agbodjinou explains that WoeLab is Togo’s first technology incubator and fabrication lab that creates sustainable technology by utilising the local environment’s electronic waste.

Having studied design and architecture in France before returning home, Agbodjinou is a believer in the power of the #LowHighTech concept to help make cities, along with residents, smarter so they are able to help come up with their own solutions.

He says that it is possible for old cities to be smart with the right interventions, “but when they want to have ‘smart’ they build a new city. What should happen to the city that we have now, should we abandon it? What we try to do is to help people in existing cities, so that in 5 or 10 years those people will build their own smart cities, using their own technology that they developed,” Agbodjinou says.

WoeLab is one of several free incubators.

“At the beginning, it was just an urban utopia. But we began to test it. We created the first network of spaces where people can come and be trained for free. We have spaces where young boys and girls can come, train and launch projects which can make the city better."

He adds: "The best of those projects we try to switch them, and make into start-ups. This way they are easy to scale and can start to make an impact. The idea of the network of projects we want to create in the city is that we want to use them like a smart-grid.”

He says that they currently run two spaces, WoeLab (the waste project) and the other one is a food project. With the latter, abandoned spaces are turned into food gardens where residents can order the food through a platform developed by the team. The buyers will be alerted via the platform when the food is ready to be collected and they can go collect at one of the labs.

With the waste project, residents who live around the neighbourhood where the lab is located register to receive a smart bin that they use to collect plastic waste. When the smart bin is full, it sends an alert and the team knows to go to the house to collect the plastic trash, which is then used to make other products.

“We have 47 people around the first lab who don’t produce any plastic waste because all their plastic waste is sent to us in the lab,” Agbodjinou says. He says the idea is that each lab be focussed on a specific problem and that eventually he wants the mini-grid to become the clean energy hubs for these areas.

“In Africa you have what we can call a spontaneous urbanism, everybody in the city changes the city. You can have someone go outside and create something in the city, so we need to take into account those informal ways of changing the city and see how we can professionalise this informal sector because you have a lot of creativity in this urbanism also. The problems we will face tomorrow in Africa are so big that we can’t count only on the politicians and experts to find solutions.”

“You need to outsource solutions even to the mass or the informal sector. The best way to do that is to provide a place where people can go and become smart by doing what they are already doing, but in a more professional way, so they also contribute to the changing of the city.”

More on the future of cities:

Tiffany Chu on redesigning the way cities build their transport routes

Michelle Mlati on her afrofuturistic approach to spatial planning

Ilze Wolff on creating an activist and public culture around architecture