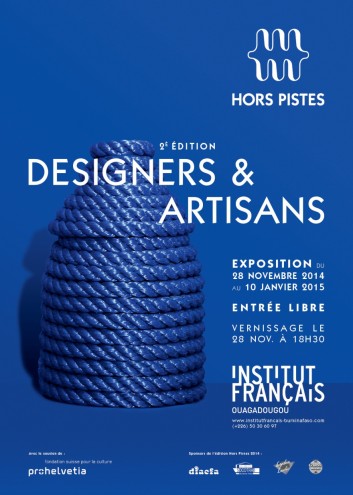

In this second of our first-person accounts from the designers in the Hors Pistes workshop in Banfora, Burkina Faso, product designer Béatrice Durandard gives us an honest insight into the dynamics of forging a real and equal collaboration between designer and artisan. “It was for me a great opportunity to discover Africa in a more realistic and personal way,” she says. Read her enlightening account of working with the Burkinabé weavers here.

First day of workshop

We arrive under the mango trees, where the workshop will take place. The 10 weavers are sitting on mats on the ground surrounded by palm leaves. They introduce themselves one by one and so do we. Each of them begins to demonstrate how they make the objects they specialise in. Here they are in automatic mode. One of them surprises me in particular, an older woman with a generous “African mama” physique. She begins to weave a mat. Looking down, a serious face, almost sullen, she works.

We observe, learn and can intervene thanks to our precious coordinator and translator, Ouahabo, who speaks Djoula. The day ends peacefully.

I like the mats. They are simple, rectangular and especially flexible. Surprisingly, they can be rolled without breaking the fibres. I love those rolls.

I start to work. We go through our translator. He is so busy that we will have to be basic. “Ouahabo, can you ask the ‘mat weaver’ to stop there and close the mat like a roll?”

Looking back, it would have been better to ask her her name again and to reintroduce myself in a more personal way. Fortunately, the weeks to come will allow us to correct this awkwardness.

She looks up, looks at us, raises her eyebrows and smiles. She seems surprised, amused and annoyed. I smile back: OK, it may seem weird for you to finish the object like that. But it will give me ideas, abstract though they might be. I am not sure that she understood all that in a simple smile, but the intention is there.

She executes. By not discussing, it’s almost like we are giving orders. It is very disturbing, and not at all like the initial collaborative idea we had... But how to proceed differently?

The weaver constructs the hybrid object with two edges joined together. I ask her not to tighten the weave. I love the shape that emerges. I thank her and go with my roll-sample. I leave her without further explanation, with her fun-vexed air. So this is going to happen for a month? Hmm….

The days pass, the ideas become clearer

I cut various flat patterns into existing mats that I fold and fix into volumes. The weavers respond with general amazement – surprise, amusement and also offence. It takes two working days to weave a mat. I have destroyed it in five minutes.

We are starting to realise the cultural differences and working methods. For them, everything goes through the hands, everything is in the present and everything is anchored. The knowledge is innate, intuitive. This is an automated system, which exists only for the single model they know how to make. There are other models that use the same braiding technique, but for them it is a new thing to be learned.

Research concepts, projection, anticipation are non-existent, not useful and therefore incomprehensible for them. The representation itself is an abstract thing: the sketches, templates and drawings are not talking to them. The change of state from unfolded mat to folded object is impossible to imagine in advance. I discover that logic, deduction and anticipation are tools that feel natural to us, but in fact require a real drive to learn, which is difficult to install in three weeks. And is that really the point?

The project takes shape

I design different volumes from flat patterns. Shaped, the weavings become wall shelves, kinds of pockets or sculptures each with their own character.

We are distinct teams. Each designer with his or her weaver.

So I work with Hilou, the mama of mats.

We have no common working method. I do not know how to weave; she does not know how to copy a form that I draw. We do not speak the same language.

I try to learn to weave, to show gestures. Hilou focusses gravely to understand the pattern carved on a square paper. Always with an annoyed air, she explains to Ouahabo that her brain has been “dead” for a long time. She is wrong, though, because somehow, day after day, the project progresses…

Our relationship evolves

Our way of communicating is set up. The only thing we have in common, finally, is being human, being women. This commonality is precious, so Hilou and I cling to it. This is what makes the work fun and is what makes us believe in the project, otherwise it would be tempting to give up.

Hilou is a bit like my African grandmother. She is full of goodwill and love, and exudes the serenity and calm of an old sage.

Two other mat weavers, Kone Sita and Sita, come in as reinforcement because time is running out.

I change my drawings based on production capacity. The irregularity of the weaving does not provide symmetrical shapes, so all the shapes are now designed asymmetrically. I also try to ensure that the weaving forms begin with the classic rectangular shape, which reassures the women when starting to make the objects.

From their side, Kone Sita and Sita are dedicated to their work, and Hilou, despite “the death of her brain” takes her role as master weaver very seriously. She shows them the new techniques for making the forms I have requested, although often it is partly misunderstood.

Between the days passing at light speed and political events that keep us from going to the workshops, everyone manages to move the project forward somehow.

The situation forces us to work without being in the same place. We give instructions in the morning by telephone, they spend their days weaving objects, taxis transport the woven objects to us in the evening. I discover the concepts Hilou does not yet grasp: for her, an angle of 90 degrees or 135 degrees is the same.

This is a good test. We realise that the women will not be able to continue production independently.

Collaborating versus teaching

It’s difficult to know at what point a collaborative way of working becomes more of a teaching/learning dynamic.

To be able to produce my object, the women need to learn different ways of starting and finishing the weaving.

By observing the other women and by experimenting with weaving myself, I learn it in a few hours. But for them, it takes a week to learn and do it by themselves without me showing them how.

So is my project too complicated for their skills? I don’t want to be a teacher, it was not the goal of the project. I changed things in the design to make it easier to produce, but maybe not enough?

However, as soon as I see that they understand the new techniques, the objects start to look good and I'm really happy with the result.

We can finally arrive at a more collaborative way of working, talking about the choice of colours and about the project itself. That was not really possible before that, because in spite of drawings and explanations, it was too difficult for Hilou to figure out what the object was.

We have reached the end of the workshop and maybe now could start a real and equal collaboration.

The work was much more difficult than I imagined it would be, but perhaps that is what made the human experience so great and the final objects so different from what I usually do.

Back in Europe

Working with people with a different knowledge base and culture was a very valuable exercise. Before the Hors Pistes workshop, my understanding of product development was simple. Either the designer defines a need, designs an object that will answer it and then finds a manufacturer to produce it; or the designer chooses a material and a manufacturer or craftsman who works with it, and then develops a project that fits their field of expertise.

I learned in Banfora that it’s not as easy as it seems as working with craftsmen with specific knowledge can evolve unexpectedly, even for the makers themselves. If it’s done smartly, the designer and craftsman can work together to create new manufacturing techniques.

Looking back now and seeing how far we can go even without having the same methods and language, I hope I will have the opportunity to test it here in Europe, where there are no communication barriers. After the experience in Banfora, I am not afraid anymore to push a project further, to take more risks and to do more challenging projects.