First Published in

In the past, jewellery as body adornment has given meaning, function, comment, pleasure, reason, identity and community. However, as the future draws closer, technology is increasingly repurposing objects and refashioning the body.

"Where are we going if new functions can be added to the body in a designed way?" asks Swiss jewellery designer Christoph Zellweger. "On a philosophical level, it challenges how we have thought about the human subject."

"In the search for improvement, ultimate functionality, beauty and perfection, the human body has become a subject of design. This will have a lasting impact on the way we define ourselves as individuals and societies," he goes on.

Born from a family of goldsmiths, silversmiths and watchmakers six-generations deep, Zellweger has been steeped in the production of preciousness and refinement from an early age. Initially trained as a goldsmith, he worked in the field of luxurious fine jewellery for more than 10 years before completing his masters at the Royal College of Art in London.

It was when his non-conformist spirit came up against the establishment's restrictive views and single-minded focus on craftsmanship, rather than expression, that Zellweger was inspired to seek an alternative outlet for his questions concerning philosophy, politics, science, genetics, ethics, nature and artifice. By using unconventional materials and developing new ways of wearing jewellery, he now attempts to bring the discourse around body modification and adornment, which has been taken over by plastic surgery, back into the field of jewellery.

"The importance and meaning of jewellery has been banalised by industrialisation and mass-production. Traditionally, jewellery had a personal meaning to its owner, but was also a significant communication tool to society as a whole. Through jewellery, we communicate who we are, which group we belong to, our preferences, our social status and our interests. Jewellery has always been a tool to express these notions," explains Zellweger.

Moreover, he goes on, we are investing money, time and thought into the body itself. "In the same way that everyone once wanted a little gold chain around their neck, now it's about the size of your breasts or the straightness of your nose. So, what I'm saying with my work is that the body itself is the new jewel, which makes it open to trivialisation, on the one hand, but also, on the other hand, of imbuing a new meaning - one can now design the body in such a way as to put meaning on to it."

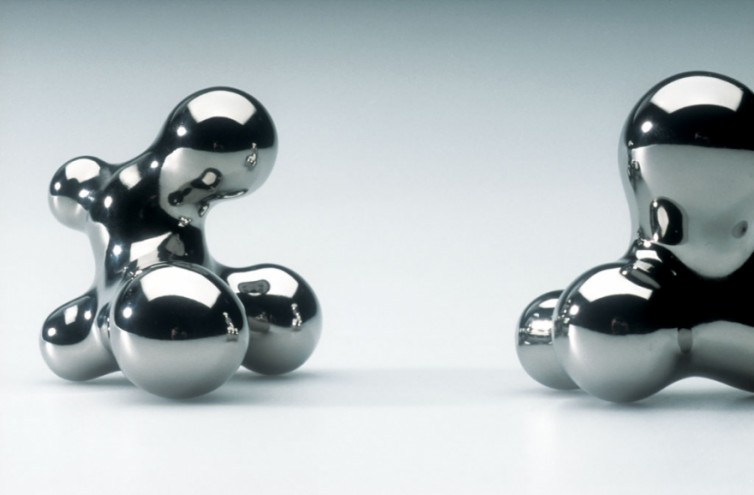

Made from highly polished stainless steel, the Foreign Bodies collection poses disquieting parallels between body organs and luxury items. Although referring to implants, they are worn on the body surface. Zellweger says he doesn't expect anyone to actually insert the pieces into the body, but he considers the possibility itself intriguing. "It is like owning a very very fast car, even though you have to comply to a speed limit," he comments.

Re-sculpting the human skeleton, the Ossarium Rosé collection poses mortality in surprisingly sensual tones through the flocked surface and impartial pink colour. Zellweger explains that he spent a lot of time on getting the colour just right - not quite flesh colour, definitely not girly, nearly nice and almost seductive. The bone-like shapes that are sometimes anatomical, sometimes not, describe the possibility of a futurist body: "What if this is a relic from the future?"

"I am concerned about my body: What if it fails and what if it becomes controlled by technology? My grandfather had a pacemaker inserted when he was 93 and he died almost five years later. I remember sitting with him one evening and he told me very quietly that it was amazing to hear the pacemaker every night, running and setting a pace, but that it was also scary because the pacemaker wouldn’t allow him to die when it was time. It was not respecting his own mental relationship to his body."

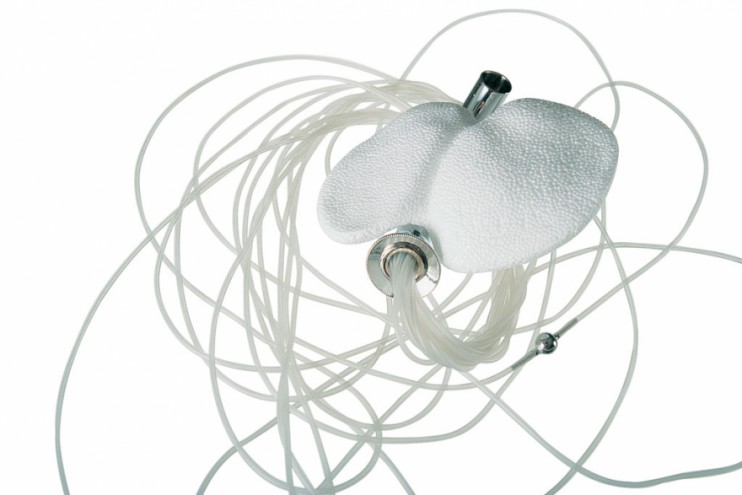

Zellweger questions the status of the human body, between nature and commodity, in the Body Pieces series, which is made out of polystyrene. "As a by-product and packaging material, polystyrene has no value or status whatsoever in society. To then make something beautiful out of it, means that someone cared. However, on another level, the name of this collection - Body Pieces - declares that our body parts are packaging for our self," says Zellweger.

A collector, he recalls, was so irritated when she saw that his new collection was made out of polystyrene that she stormed out of his exhibition. The next morning, first thing, she was back. She hadn't slept much that night, instead fuming that she had found such a horrible material as polystyrene beautiful. "I will never look at polystyrene in the same way again," she said. "Maybe I can inspire that reaction regarding the human body," says Zellweger.

The possibility of working in these unconventional materials is reliant on Zellweger's interest in technology and technique - he worked for almost three years to develop a technique that could present polystyrene in an acceptable way. "I am interested in what I don't know, the unexpected. So I choose technologies that at the beginning I can not control and at the end of a long process come up with an image, a reading of the things I make, that surprises me. When this happens I know that it will probably surprise others as well," he says.

It was this process that led him to his rubber-based Rhizome series. The project was inspired by Zellweger's observation that it is very difficult to find a truly original pattern and that most of the patterns being used in the decorative arts had been around for centuries, inspired by nature. He set out to develop a contemporary pattern that represents his "feeling of our time and came to Rhizome. It took him almost three months until it felt right.

Just like the Foreign Bodies collection, Zellweger's work in rubber demands to be worn in different ways, evoking a sensual, tactile experience. "It is not different to how a furniture designer explores new ways of sitting," Zellweger explains. The Body Supports collection comprises belts, braces, harnesses and straps designed as "emotional prostheses for the contemporary individual" - though some are even designed to be worn by couples.

Significantly, it seems that Zellweger's work itself has changed his relationship with his own body and adornment. "I used to wear jewellery, but I don't any more because I don't want to talk constantly about the pieces. As soon as I do wear jewellery, the conversation turns to me and what I do," he laughs.

"The whole jewellery industry works on this idea of creating community and distinction at the same time. We want to look like each other but we are also constantly looking for subtle distinctions. The idea behind jewellery is to make a piece that draws compliments from friends, family and society, on one hand confirming that one is part of the group and, on the other hand, wanting people to say that it is really different and special. However, it can be so special as to not belong to the same community anymore and create a new one," Zellweger concludes.