From the Series

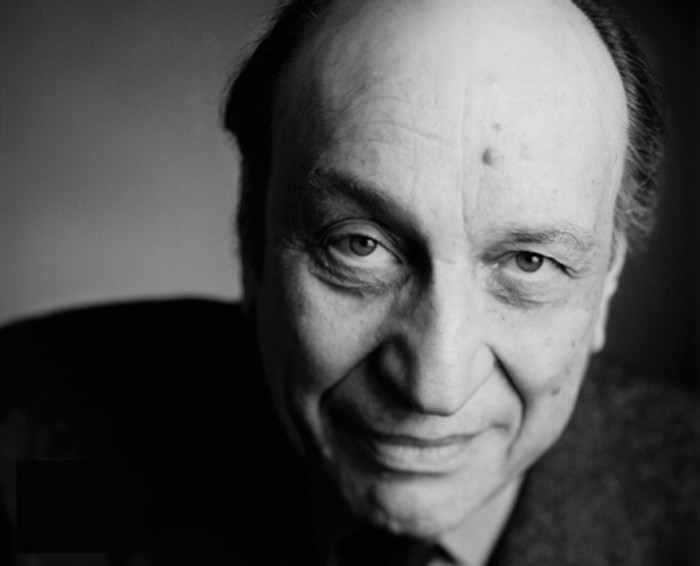

To many, Milton Glaser is the embodiment of American graphic design during the latter half of the 20th century. His presence and impact on the profession internationally is formidable. Immensely creative and articulate, he brings a depth of understanding and conceptual thinking, combined with a diverse richness of visual language, to his work.

A graphic design giant he may be, but Glaser's output is also characterised by a great generosity of spirit. In this essay, adapted from a talk that he gave at a conference for AIGA, the American professional association for design, he takes stock of what he has learned in his career – from working with people, to being professional, to how to stay relevant as a designer. It dates back to 2011, but we think his candid and humorous advice is timeless.

1. Only work for people you like.

This is a curious rule and it took me a long time to learn because, in fact, at the beginning of my practice I felt the opposite. Professionalism required that you didn’t particularly like the people that you worked for or at least maintained an arm's-length relationship to them, which meant that I never had lunch with a client or saw them socially. Then some years ago I realised that the opposite was true. I discovered that all the work I had done that was meaningful and significant came out of an affectionate relationship with a client. And I am not talking about professionalism; I am talking about affection. I am talking about a client and you sharing some common ground. That, in fact, your view of life is someway congruent with the client, otherwise it is a bitter and hopeless struggle.

2. If you have a choice, never have a job.

One night I was sitting in my car outside Columbia University where my wife, Shirley, was studying anthropology. While I was waiting I was listening to the radio and heard an interviewer ask “Now that you have reached 75 have you any advice for our audience about how to prepare for old age?” An irritated voice said, “Why is everyone asking me about old age these days?” I recognised the voice as John Cage. I am sure that many of you know who he was – the composer and philosopher who influenced people such as Jasper Johns and Merce Cunningham as well as the music world in general. I knew him slightly and admired his contribution to our times. “You know, I do know how to prepare for old age,” he said. “Never have a job, because if you have a job someday someone will take it away from you and then you will be unprepared for your old age. For me, it has always been the same ever since the age of 12. I wake up in the morning and I try to figure out 'How am I going to put bread on the table today?' It is the same at 75, I wake up every morning and I think 'How am I going to put bread on the table today?' I am exceedingly well prepared for my old age,” he said.

3. Some people are toxic. Avoid them.

This is a subtext of number one. In the 1960s there was a man named Fritz Perls who was a Gestalt therapist. Gestalt therapy derives from art history; it proposes you must understand the ‘whole’ before you can understand the details. What you have to look at is the entire culture, the entire family and community and so on. Perls proposed that in all relationships people could be either toxic or nourishing towards one another. It is not necessarily true that the same person will be toxic or nourishing in every relationship, but the combination of any two people in a relationship produces toxic or nourishing consequences. And the important thing that I can tell you is that there is a test to determine whether someone is toxic or nourishing in your relationship with them. Here is the test: You have spent some time with this person, either you have a drink or go for dinner or you go to a ball game. It doesn’t matter very much, but at the end of that time you observe whether you are more energised or less energised. Whether you are tired or whether you are exhilarated. If you are more tired, then you have been poisoned. If you have more energy, you have been nourished. The test is almost infallible and I suggest that you use it for the rest of your life.

4. Professionalism is not enough, or The 'good' is the enemy of the 'great'.

Early in my career I wanted to be professional. That was my complete aspiration in my early life because professionals seemed to know everything – not to mention they got paid for it. Later I discovered after working for a while that professionalism itself was a limitation. After all, what professionalism means in most cases is diminishing risks. So if you want to get your car fixed you go to a mechanic who knows how to deal with transmission problems in the same way each time. I suppose if you needed brain surgery you wouldn’t want the doctor to fool around and invent a new way of connecting your nerve endings. Please do it in the way that has worked in the past. Unfortunately in our field, in the so-called "creative"... I hate that word because it is misused so often. I also hate the fact that it is used as a noun. Can you imagine calling someone a creative? Anyhow, when you are doing something in a recurring way to diminish risk or doing it in the same way as you have done it before, it is clear why professionalism is not enough.

After all, what is required in our field, more than anything else, is the continuous transgression.

Professionalism does not allow for that because transgression has to encompass the possibility of failure and if you are professional your instinct is not to fail – it is to repeat success. So professionalism as a lifetime aspiration is a limited goal.

5. Less is not necessarily more.

Being a child of modernism I have heard this mantra all my life. Less is more.

One morning upon awakening, I realised that it was total nonsense. It is an absurd proposition and also fairly meaningless. But it sounds great because it contains within it a paradox that is resistant to understanding. But it simply does not obtain when you think about the visual history of the world.

If you look at a Persian rug, you cannot say that less is more because you realise that every part of that rug, every change of colour, every shift in form is absolutely essential for its aesthetic success.

You cannot prove to me that a solid blue rug is in any way superior. That also goes for the work of Gaudi, Persian miniatures, Art Nouveau and everything else. However, I have an alternative to the proposition that I believe is more appropriate. “Just enough is more.”

6. Style is not to be trusted.

I think this idea first occurred to me when I was looking at a marvelous etching of a bull by Picasso. It was an illustration for a story by Balzac called The Hidden Masterpiece. I am sure that you all know it. It is a bull that is expressed in 12 different styles going from a very naturalistic version of a bull to an absolutely reductive single line abstraction and everything else along the way. What is clear just from looking at this single print is that style is irrelevant. Every one of these cases, from extreme abstraction to acute naturalism, are extraordinary regardless of the style. It’s absurd to be loyal to a style. It does not deserve your loyalty.

I must say that for old design professionals it is a problem because the field is driven by economic consideration more than anything else. Style change is usually linked to economic factors, as all of you know who have read Marx. Also, fatigue occurs when people see too much of the same thing too often. So every ten years or so, there is a stylistic shift and things are made to look different. Typefaces go in and out of style and the visual system shifts a little bit.

If you are around for a long time as a designer, you have an essential problem of what to do. I mean, after all, you have developed a vocabulary, a form that is your own.

It is one of the ways that you distinguish yourself from your peers, and establish your identity in the field. How you maintain your own belief system and preferences becomes a real balancing act. The question of whether you pursue change or whether you maintain your own distinct form becomes difficult.

We have all seen the work of illustrious practitioners that suddenly looks old-fashioned or, more precisely, belonging to another moment in time. And there are sad stories such as the one about Cassandre, arguably the greatest graphic designer of the 20th century, who couldn’t make a living at the end of his life and committed suicide. But the point is that anybody who is in this for the long haul has to decide how to respond to change in the zeitgeist. What is it that people now expect that they formerly didn’t want? And how to respond to that desire in a way that doesn’t change your sense of integrity and purpose?

7. How you live changes your brain.

The brain is the most responsive organ of the body. Actually it is the organ that is most susceptible to change and regeneration of all the organs in the body. I have a friend named Gerald Edelman who was a great scholar of brain studies and he says that the analogy of the brain to a computer is pathetic. The brain is actually more like an overgrown garden that is constantly growing and throwing off seeds, regenerating and so on. He believes that the brain is susceptible, in a way that we are not fully conscious of, to almost every experience of our life and every encounter we have.

I was fascinated by a story in a newspaper a few years ago about the search for perfect pitch. A group of scientists decided that they were going to find out why certain people have perfect pitch. You know certain people hear a note precisely and are able to replicate it at exactly the right pitch. Some people have relevant pitch; perfect pitch is rare even among musicians. The scientists discovered – I don’t know how – that among people with perfect pitch the brain was different. Certain lobes of the brain had undergone some change or deformation that was always present with those who had perfect pitch. This was interesting enough in itself. But then they discovered something even more fascinating. If you took a bunch of kids and taught them to play the violin at the age of four or five, after a couple of years some of them developed perfect pitch, and in all of those cases their brain structure had changed.

Well, what could that mean for the rest of us? We tend to believe that the mind affects the body and the body affects the mind, although we do not generally believe that everything we do affects the brain. I am convinced that if someone was to yell at me from across the street, my brain could be affected and my life might change. That is why your mother always said, “Don’t hang out with those bad kids.” Mama was right.

Thought changes our life and our behaviour.

I also believe that drawing works in the same way. I am a great advocate of drawing, not in order to become an illustrator, but because I believe drawing changes the brain in the same way as the search to create the right note changes the brain of a violinist. Drawing also makes you attentive. It makes you pay attention to what you are looking at, which is not so easy.

8. Doubt is better than confidence.

Everyone always talks about confidence in believing what you do. I remember once going to a yoga class where the teacher said that, spirituality speaking, if you believe you have achieved enlightenment you have merely arrived at your limitation. I think that is also true in a practical sense. Deeply held beliefs of any kind prevent you from being open to experience, which is why I find all firmly held ideological positions questionable. It makes me nervous when someone believes too deeply or too much. I think that being sceptical and questioning all deeply held beliefs is essential. Of course, we must know the difference between scepticism and cynicism because cynicism is as much a restriction of one’s openness to the world as passionate belief is. They are sort of twins.

Then in a very real way, solving any problem is more important than being right. There is a significant sense of self-righteousness in both the art and design world. Perhaps it begins at school. Art school often begins with the Ayn Rand model of the single personality resisting the ideas of the surrounding culture. The theory of the avant-garde is that as an individual you can transform the world, which is true up to a point. One of the signs of a damaged ego is absolute certainty. Schools encourage the idea of not compromising and defending your work at all costs. Well, the issue at work is usually all about the nature of compromise. You just have to know what to compromise.

Blind pursuit of your own ends, which excludes the possibility that others may be right, does not allow for the fact that in design we are always dealing with a triad – the client, the audience and you.

Ideally, making everyone win through acts of accommodation is desirable. But self-righteousness is often the enemy. Self-righteousness and narcissism generally come out of some sort of childhood trauma, which we do not have to go into. It is a consistently difficult thing in human affairs. Some years ago, I read a most remarkable thing about love, which also applies to the nature of co-existing with others. It was a quotation from Iris Murdoch in her obituary. It read, “Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.” Isn’t that fantastic! The best insight on the subject of love that one can imagine.

9. It does not matter what you think.

Last year, someone gave me a charming book by Roger Rosenblatt called Ageing Gracefully. I got it on my birthday. I did not appreciate the title at the time but it contains a series of rules for ageing gracefully. The first rule is the best. Rule number one is that “it doesn’t matter.” “It doesn’t matter what you think. Follow this rule and it will add decades to your life. It does not matter if you are late or early, if you are here or there, if you said it or didn’t say it, if you are clever or if you were stupid. If you were having a bad hair day or a no hair day or if your boss looks at you cockeyed or your boyfriend or girlfriend looks at you cockeyed, if you are cockeyed. If you don’t get that promotion or prize or house or if you do – it doesn’t matter.” Wisdom at last.

Then I heard a marvellous joke that seemed related to rule number ten. A butcher was opening his market one morning and as he did, a rabbit popped his head through the door. The butcher was surprised when the rabbit inquired, “Got any cabbage?” The butcher said, “This is a meat market – we sell meat, not vegetables.” The rabbit hopped off. The next day the butcher is opening the shop and sure enough the rabbit pops his head round and says, “You got any cabbage?” The butcher now irritated says, “Listen you little rodent, I told you yesterday we sell meat, we do not sell vegetables and the next time you come here I am going to grab you by the throat and nail those floppy ears to the floor.” The rabbit disappeared hastily and nothing happened for a week. Then one morning the rabbit popped his head around the corner and said, “Got any nails?” The butcher said, “No.” The rabbit said, “Ok. Got any cabbage?”

10. Tell the truth.

The rabbit joke is relevant because it occurred to me that looking for a cabbage in a butcher’s shop might be like looking for ethics in the design field. It may not be the most obvious place to find it either. It’s interesting to observe that in AIGA’s new code of ethics there is a significant amount of useful information about appropriate behaviour towards clients and other designers, but not a word about a designer’s relationship to the public. We expect a butcher to sell us eatable meat and not to misrepresent his wares.

I remember reading that during the Stalin years in Russia everything labelled veal was actually chicken. I can’t imagine what everything labelled chicken was.

We can accept certain kinds of misrepresentation, such as fudging about the amount of fat in his hamburger, but once a butcher knowingly sells us spoiled meat we go elsewhere. As a designer, do we have less responsibility to our public than a butcher? Everyone interested in licensing our field might note that the reason licensing has been invented is to protect the public, not designers or clients. “Do no harm” is an admonition to doctors concerning their relationship to their patients, not to their fellow practitioners or the drug companies. If we were licensed, telling the truth might become more central to what we do.