From the Series

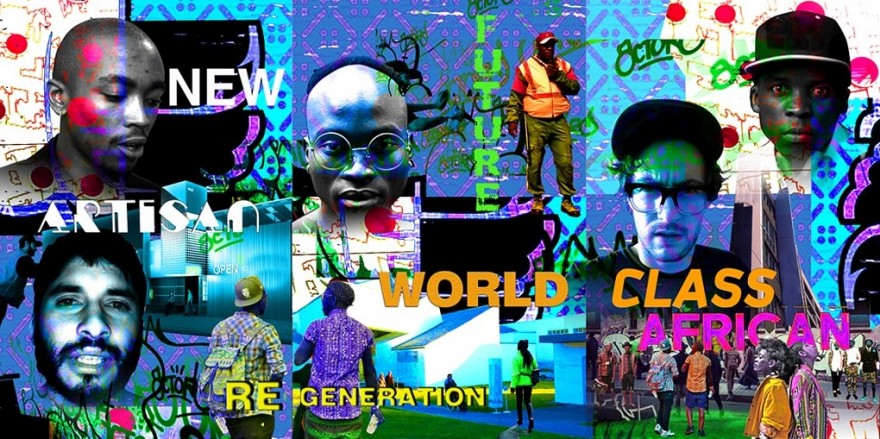

“The internet is bursting with the word ‘Afrofuturism’,” says the Kenyan digital artist known simply as Jepchumba. It conjures up both utopian and dystopian images of cyberpunk tribal warriors and aliens swarming onto the Serengeti that have a place only in fantasy. The problem is that it’s become a catchy way to describe anything involving digital technology in Africa.

“When I started my research, Afrofuturism was the hot word for anything associated with technology and art in Africa,” says Tegan Bristow, who is currently doing a PhD on digital art in Africa. The problem was that it wasn’t a term the artists themselves used to describe what they did.

“Artists like Spoek Mathambo and Dineo Sishee Bopape were suddenly given this title. This was distressing for them, they weren’t happy about it at all,” she recalls. That’s because Afrofuturism was a movement that took place in the US in the 1970s, and bringing it back conflates what’s happening now with that.

This is the thread underlying Post African Futures, an exhibition at the Johannesburg Goodman Gallery curated by Bristow, an interactive media artist who changed her focus as a fine art student when she landed up in a Computer Science 101 class by mistake.

What these artists are doing is not something that happened in the 70s in the States. It’s what’s happening to them now in Africa.

There’s a lot to wade through when it comes to group shows of pan-African art, especially when it’s an exhibition looking at questions of identity and representation. And as we all know, it’s a minefield that we’re still delicately picking our way through. The academics, galleries and art critics don’t help; their statements are cloaked in complex concepts that get stuck in your throat. We find ourselves lapsing into embarrassing generalities based on our thin knowledge of the wild and multifarious diversity of countries, ethnicities and sub-cultures covering the enormous expanse of the continent.

Jepchumba thinks this is amplified online, although she admits that it’s a trap she falls into herself. “There’s a danger when we speak about Africa… Africa is usually lobbed into one massive conglomeration of ‘Afro-ism’, especially online,” she says. “On the web, Africa is a country overrun with overused clichés. As new technology draws closer, I often wonder what ‘Africa’ really means…” she muses in a podcast series for her Future Lab Africa project.

But in her everyday life the Kenyan, who now calls Cape Town home, sees herself as one of 300 million digital Africans, inhabitants of an “Africa of 1s and 0s” for whom “chatting, texting, sharing, posting, charging” is as much second nature as it is for the Japanese or Americans.

“Technology is embedded in our daily lives and therefore becoming more embedded in culture and in how we engage with each other,” says Bristow. “It’s important for artists to be working in that medium…"

As an artist technology becomes like a material that you work with and do things with. You’re also in a position to critique that space, to ask questions about it.

She has been making it her mission to discover the “cultures of technology” that exist in Johannesburg, Nairobi and Lagos.

She is doing this for her doctoral research to bring some specificity and clarity to the depiction of technology in Africa.

“Any literature on Africa and technology didn’t understand that within Africa there are multiple existences with their own socio-cultural, political and economic histories,” she says.

The three African cities she has selected are almost case studies of extreme difference in the way their creative communities see technology. In her eyes, for instance, the legacy of Joburg’s culture of technology can be traced directly to Apartheid – “the previous regime’s use of data and computing to organise, control and segregate”.

In South Africa’s big bad commercial capital, technology carries connotations of power and ownership. “When Apartheid ended, all those computer experts went into the banking sector. The weight of power in technology sits in banking and in broadcast media in Joburg,” she notes. “There has been little innovation because we are stuck in a hierarchy of ownership. People don’t feel it belongs to them and that they can do anything with it.”

We’re trapped in a lumbering, hostile system, bouncing from 1s to 0s without wrestling control of them ourselves.

This is in stark contrast with Nairobi, Bristow says, which has a different political history. “At the end of [President Daniel Arap] Moi’s regime, which was a restricted time, things opened up radically. A lot of mobile media came into the country almost at the same time as lots of people from the Diaspora were returning to thecountry.” She points to innovations like the crowd-sourced info-mapping software Ushahidi that were developed at that time.

“Great minds who had left Kenya came back into a much more open, more accessible country. I found that Kenyan artists and practitioners understood technology as a very socially driven endeavor. You could use it for social justice, to change things, to make sure everyone is connected and their stories are told,” she notes.

In Joburg it’s the extreme opposite: it’s about the glitch, it’s very violent and abrasive.

Yikes. Dystopian, yes. Afrofuturist, no.

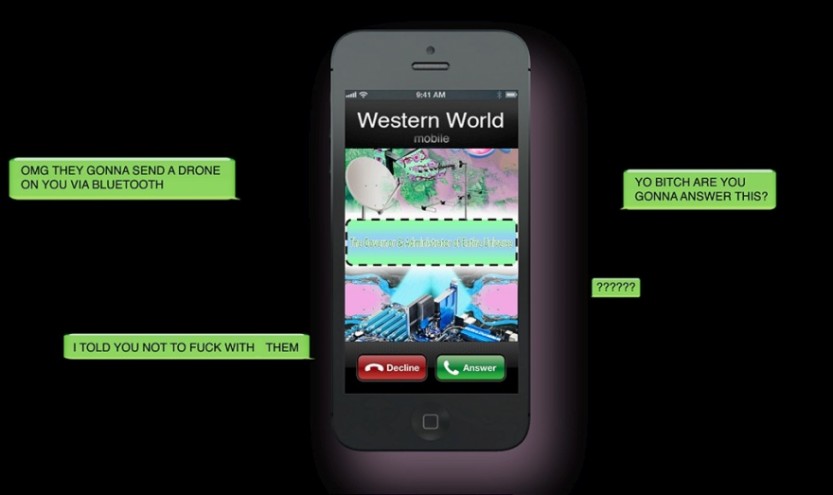

The Post African Futures exhibition offers up a multi-faceted view of how different artists are working with digital technology. There is the amusing depiction of the West’s relationship with Africa as an SMS conversation by Tabita Rezaire, a French-Guyanese and Danish new media artist based in Johannesburg. “Sorry for real” is a virtual apology on behalf of the Western world.

“Migration” by Jean Katambayi Mukendi isanimaginary machinemade of paper, cardboard and copper wirethatshows his technical interest in mathematics translated through handmade sculpture. Mukendi grew up on a mining site in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where art was of little consequence. The influence of his father, a mine technician, nonetheless comes through in his technical precision.

The installation by NTU provides decolonial therapies for the digital age. NTU is an agency founded by “tech healers” and artists Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Nolan Oswald Dennis and Tabita Rezaire, that looks towards the internet as a spiritual tool.

Jepbumba’s “Don’t Shoot” was inspired by the #blacklivesmatter movement in social media in response to the race-related police shootings in the US. “My work places the black male body at the centre of inquiry, identifying the influence of social media movements that have politicised the black body,” she explains.

The art is so diverse in the stories they tell and the media they use that it brings the message home: we are only just scratching the surface of a myriad creative ways digital technology is informing and being informed by our lives on the African continent.

"Post African Futures" is on at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg until 20 June.