First Published in

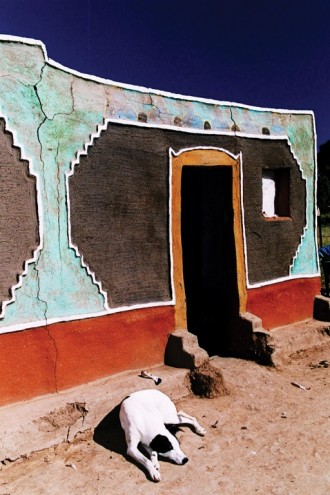

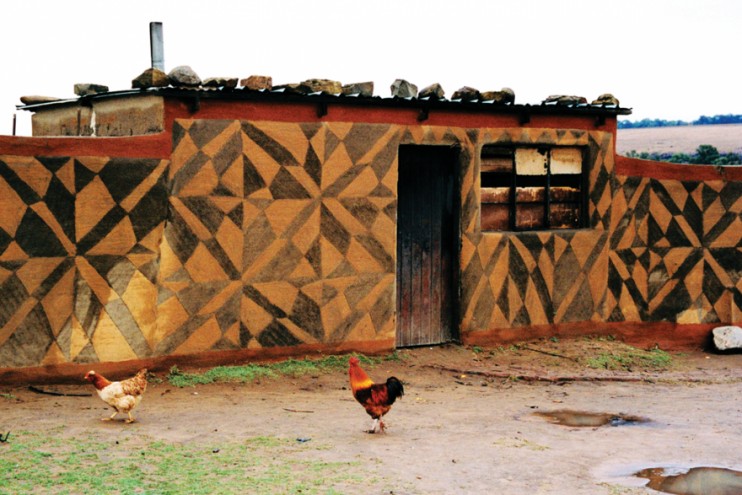

It is a tradition where women decorate a house after the men have finished building the house. These highly decorative designs are soft and flowing geometric patterns that are applied with fingers, forks and sticks on the walls of houses.The patterns are sometimes coloured with natural pigments or commercial paint and stains. Stones, embedded in mud and relief designs are sometimes used as a more permanent effect.

The word Litema (pronounced as "di-the-ma") is derived from the word "ho lema" which means to cultivate, and "tema", which denotes a ploughed field. The geometric patterns appeared initially on the inside of dwellings and it was only in the 19th century that it appeared on the outside of homes. In contemporary times the practice of Litema appears to be a seasonal phenomenon associated with special events such as celebrations and religious ceremonies. It not only announces births, deaths, weddings or the arrival of Christmas and Easter, but also serves as a reminder of the passage of time.

In 1976 a certain Mr. Motibe from the Lesotho National Teachers' Training College expressed his fear that Litema was in fact a disappearing art form. Even today, nearly thirty years later, urbanisation, the use of concrete and modern paints contribute to the demise of this indigenous form of decoration and art.

Before important events, an entire village might be decorated. Traditionally a chief artist or advisor was called upon to direct and advise the women of the village on the types of design or methods of application. The special occasion became a social event in itself. Whilst squatting and drinking tea, the most skilled Litema artist would sketch her intentions in the dust. Once consensus on a design had been reached, women set out to work. Nowadays, it appears, each woman (possibly joined by members of her household and daughters) prefers her individual design and house decoration. The start of decorating times are greeted with much excitement from friends and neighbours who generously participate in terms of giving advice and moral support. Thus it is still an opportunity for a social get-together. The tradition of mural art in Southern Africa, and in particular the tradition of Litema, is not of recent origins.

One of the oldest written accounts of these murals is by a missionary John Campbell. In 1812 Campbell, in an attempt to establish diplomatic relations, visited the house of a certain chief Sinosee of the Hurutse lineage of the Tswana. He provided both illustrations as well as a verbal description of the chief's house. His description on these unique ornamented walls were extremely enthusiastic:

"Its walls were decorated with delightful representations of elephants and giraffes…In some houses there were figures, pillars, etc moulded in hard clay and painted with different colours that would not have disgraced European workmen. They are an ingenious people."

In 1880, the historian George Stow brought Campbell's accounts together. Stow, in his 1905 book titled The Native Races of South-Africa, reproduced four designs made by the Bakuena (from Botswana), then living in South Africa. In his book, he suggests that the traditional skills of mural painting described by Campbell were still very much alive - this time in South Africa. Stow's drawings are of textured panels similar to Litema engravings. Other illustrations show simple patterns of dots, stripes, triangles and zigzags executed in limited colours. In 1861, Eugene Casallis, a French missionary who worked in the Free State/ Lesotho region, referred to the Litema design as "ingenious" and far more intricate than those suggested by Stow.

More than a century separates Stow's drawings from those drawings done by Motibe's students in 1976 of the Lesotho National Teachers' Training College. Students collected 29 designs for the purpose of using these in classroom geometry lessons and to copy them for potato prints. These drawing were given names such as Lekoko, Lithebe, Litepo, and Moseme to name but a few. The English interpretations of these names are animal skin, shields, spider web, and reed mat, leading a person to believe that the underlying influence for these designs came from the artists' immediate environment. The most common opinion seems to be the copying of linear patterns resembling the furrows found in ploughed fields or field lying empty after harvesting. It is also very clear that the types of patterns mostly resemble natural forms such as leaves, corn seeds and flowers. Others suggest that more modern-day forms might influence designs - articles such as Dutch delft (these articles are often found in Basotho homesteads), pictures from magazines and specifically traditional Basotho blankets. The traditional Basotho blankets in turn display an Art Nouveau design style, reminiscent of the Victorian era. On close inspection some of the patterns found in Litema designs actually do resemble the Dutch delft articles. In fact, some of the patterns illustrated in Motibe's booklet are exact copies of patterns found on Basotho blankets.

Like flowers, Litema blooms with the arrival of spring and wilts with the approach of winter. It dies with the temporary surface of mud it adorns. As the suns dries and cracks the design, the rains come to wash away the 'dead' design, making way for new decorative opportunities.

About the author and photographer

Rudi de Lange completed his training in graphic design at the East London Technical College, practiced as a designer and photographer and lectured in these fields. He studied for a while in England and later completed a Ph.D. at the University of Stellenbosh. His research is in the field of visual communication/visual literacy with application in education, communication and primary health care. He is currently the Director and Head of the School for Design Technology and Visual Art at Technikon Free State. He is a Board member of the International Visual Literacy Association (IVLA.org), and serves as the National President of the Design Educators Forum of Southern Africa.

In 1994 Carina Mylene Beyer returned to Swakopmund, Namibia after completing her studies in photography at the Technikon Free State in Bloemfontein. She worked for 6 years as a wedding-, portraiture- and advertising photographer, specialising in cibachrome and fine art printing. Carina is currently employed as a photography lecturer at the Technikon Free State and DCM Design Institute, as well as furthering her studies in photography and conducting research on the origins and symbolism of Basotho house painting designs, otherwise known as Litema.

It is a tradition where women decorate a house after the men have finished building the house. These highly decorative designs are soft and flowing geometric patterns that are applied with fingers, forks and sticks on the walls of houses.The patterns are sometimes coloured with natural pigments or commercial paint and stains. Stones, embedded in mud and relief designs are sometimes used as a more permanent effect.

The word Litema (pronounced as "di-the-ma") is derived from the word "ho lema" which means to cultivate, and "tema", which denotes a ploughed field. The geometric patterns appeared initially on the inside of dwellings and it was only in the 19th century that it appeared on the outside of homes. In contemporary times the practice of Litema appears to be a seasonal phenomenon associated with special events such as celebrations and religious ceremonies. It not only announces births, deaths, weddings or the arrival of Christmas and Easter, but also serves as a reminder of the passage of time.

In 1976 a certain Mr. Motibe from the Lesotho National Teachers' Training College expressed his fear that Litema was in fact a disappearing art form. Even today, nearly thirty years later, urbanisation, the use of concrete and modern paints contribute to the demise of this indigenous form of decoration and art.

Before important events, an entire village might be decorated. Traditionally a chief artist or advisor was called upon to direct and advise the women of the village on the types of design or methods of application. The special occasion became a social event in itself. Whilst squatting and drinking tea, the most skilled Litema artist would sketch her intentions in the dust. Once consensus on a design had been reached, women set out to work. Nowadays, it appears, each woman (possibly joined by members of her household and daughters) prefers her individual design and house decoration. The start of decorating times are greeted with much excitement from friends and neighbours who generously participate in terms of giving advice and moral support. Thus it is still an opportunity for a social get-together. The tradition of mural art in Southern Africa, and in particular the tradition of Litema, is not of recent origins.

One of the oldest written accounts of these murals is by a missionary John Campbell. In 1812 Campbell, in an attempt to establish diplomatic relations, visited the house of a certain chief Sinosee of the Hurutse lineage of the Tswana. He provided both illustrations as well as a verbal description of the chief's house. His description on these unique ornamented walls were extremely enthusiastic: "Its walls were decorated with delightful representations of elephants and giraffes…In some houses there were figures, pillars, etc moulded in hard clay and painted with different colours that would not have disgraced European workmen. They are an ingenious people."

In 1880, the historian George Stow brought Campbell's accounts together. Stow, in his 1905 book titled The Native Races of South-Africa, reproduced four designs made by the Bakuena (from Botswana), then living in South Africa. In his book, he suggests that the traditional skills of mural painting described by Campbell were still very much alive - this time in South Africa. Stow's drawings are of textured panels similar to Litema engravings. Other illustrations show simple patterns of dots, stripes, triangles and zigzags executed in limited colours. In 1861, Eugene Casallis, a French missionary who worked in the Free State/ Lesotho region, referred to the Litema design as "ingenious" and far more intricate than those suggested by Stow.

More than a century separates Stow's drawings from those drawings done by Motibe's students in 1976 of the Lesotho National Teachers' Training College. Students collected 29 designs for the purpose of using these in classroom geometry lessons and to copy them for potato prints. These drawing were given names such as Lekoko, Lithebe, Litepo, and Moseme to name but a few. The English interpretations of these names are animal skin, shields, spider web, and reed mat, leading a person to believe that the underlying influence for these designs came from the artists' immediate environment. The most common opinion seems to be the copying of linear patterns resembling the furrows found in ploughed fields or field lying empty after harvesting. It is also very clear that the types of patterns mostly resemble natural forms such as leaves, corn seeds and flowers. Others suggest that more modern-day forms might influence designs - articles such as Dutch delft (these articles are often found in Basotho homesteads), pictures from magazines and specifically traditional Basotho blankets. The traditional Basotho blankets in turn display an Art Nouveau design style, reminiscent of the Victorian era. On close inspection some of the patterns found in Litema designs actually do resemble the Dutch delft articles. In fact, some of the patterns illustrated in Motibe's booklet are exact copies of patterns found on Basotho blankets.

Like flowers, Litema blooms with the arrival of spring and wilts with the approach of winter. It dies with the temporary surface of mud it adorns. As the suns dries and cracks the design, the rains come to wash away the 'dead' design, making way for new decorative opportunities.

About the author and photographer

Rudi de Lange completed his training in graphic design at the East London Technical College, practiced as a designer and photographer and lectured in these fields. He studied for a while in England and later completed a Ph.D. at the University of Stellenbosh. His research is in the field of visual communication/visual literacy with application in education, communication and primary health care. He is currently the Director and Head of the School for Design Technology and Visual Art at Technikon Free State. He is a Board member of the International Visual Literacy Association (IVLA.org), and serves as the National President of the Design Educators Forum of Southern Africa.

In 1994 Carina Mylene Beyer returned to Swakopmund, Namibia after completing her studies in photography at the Technikon Free State in Bloemfontein. She worked for 6 years as a wedding-, portraiture- and advertising photographer, specialising in cibachrome and fine art printing. Carina is currently employed as a photography lecturer at the Technikon Free State and DCM Design Institute, as well as furthering her studies in photography and conducting research on the origins and symbolism of Basotho house painting designs, otherwise known as Litema.