There is an Arabic proverb often cited by Agnieszka Dobrowolska, director of ARCHiNOS Architecture, that says "who forgets the past is lost”. The firm, established in 2008, focusses primarily on historic buildings and designing in a historic context – and its base, Cairo, offers immense scope for such specialisation.

A tiny sample of ARCHiNOS projects in the 1 300-year-old city includes the restoration of Ottoman-era treasures, a late-Mamluk-style hawd (building that provided drinking water) in the City of the Dead and conservation of a mosque dating back to the 12th century.

Yet the firm’s engagement with antiquity is far from sentimental.

“Material documents of the past like the historic built environment are not just nostalgic memorabilia, to be sold to tourists as postcard images,” says Dobrowolska. “In many subtly interconnected ways they are part of our present and determine our future. Historic preservation is not an antiquarian activity, it is working in the present for the future.”

Dobrowolska and her husband, Jaroslaw Dobrowolski, trained in Warsaw, Poland, where they were born. They began documenting archaeological excavations and working on related conservation projects for the Polish Archaeological Centre in Cairo and other foreign and Egyptian institutions and agencies, and eventually moved to the city.

The firm has a small core staff of Egyptian architects, and commissions other staff and specialists depending on a specific project’s needs.

“Cairo is an extremely rich and diversified environment,” says Agnieszka. “‘Cairo is not a city, but a universe,’ as author Ursula Lindsey aptly put it. The official index of historic monuments in the city lists about 500 entries – and these are almost exclusively mediaeval and Ottoman-period buildings.

There are literally thousands of historic buildings of interest and of great aesthetic value outside of this listing in Cairo.

The historical buildings do not exist in a vacuum.

Agnieszka describes Cairo as a living, mediaeval city where time-honoured ways of life can still be found, but intriguingly, “aspects of close-knit community life have been passed on to modern districts”. Here, the past feeds into the structure of the present.

ARCHiNOS is particularly aware of this ongoing exchange and how it reflects on the cultural landscape.

“We understand heritage not as a collection of aged buildings, but as both material and intangible document of conditions, ideas, customs and values of the society that created it, and moreover, as a living organism in constant interaction with the people who use and continually modify it,” says Agnieszka.

The people on the streets of mediaeval Cairo – their crafts, customs, dress, food, ideas – are as much part of the urban cultural landscape as the magnificent monuments.

ARCHiNOS’s work is not limited to historic work, or just one city. They have worked on numerous projects, including a new Museum of Arabic Calligraphy in the Alexandria Museum of Fine Arts, and homes and museums in Beirut and Bahrain.

Here the architects tells us about the philosophy and methods ARCHiNOS employs in its restoration and museum work, specifically in Cairo.

How does it feel to make a contribution to preserving Cairo’s cultural history?

There are surprising similarities between the work of an architectural conservator and the medical profession. Like people, buildings suffer, age, and die. Conservation aims at slowing down the process of decay, but it cannot reverse it. Any conservation intervention, no matter how thorough, is not the ‘end of history’ for the building that is treated; it is merely another phase in its life. Stones in any historic building have stories to tell, and sometimes you can hear a suffering or dying building cry for help almost audibly. If we do our job right, there is a good chance that the buildings we conserve will outlive us, like we expect our children to do.

Your design philosophy notes that “we create designs that take into account the historic and cultural heritage of every site”. Can you give us some concrete examples?

When designing a mosque in Cairo to replace a collapsed one, we take the values and expectations of people in the traditional local community into consideration. They will use the building long after our work is finished.

Sometimes in architectural conservation we prefer our input to be invisible for a casual visitor, while – as conservation ethics requires — all modern interventions are distinguishable from the original material, do not falsify historical evidence and respect different phases in the building’s history.

In some cases it may be appropriate to introduce contemporary additions of modern forms, contrasting with the original materials and finishes in a historic setting. In other cases modern interventions have to withdraw completely into the background so as not to interfere with historic architecture – there is no universal recipe.

Quite possibly only future generations will pass the verdict on our work. This is why we put emphasis on values that are not subject to fashion, to intellectual or aesthetic vogue, but on human scale, the inherent qualities of various materials, structural and functional soundness and clarity, and good craftsmanship.

Are there sufficient craftspeople to reproduce or repair the historical materials needed for your restoration work?

In Cairo, many traditional crafts are still practised in countless small, family-owned workshops, where secrets of the trade are passed from fathers to sons. We attempt to use materials and techniques as similar as possible to those used in the original construction; usually perfectly feasible in Cairo.

One recently completed project was the restoration of an Ottoman-period building whose ornate façade was completely destroyed by fire in 2009. This left a dreadful scar in the tissue of one of the most important urban landscapes in Cairo.

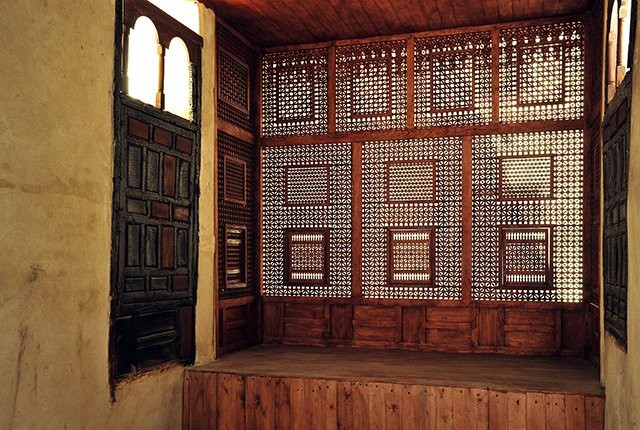

The Cultural Emergency Response programme of the Dutch Prince Claus Foundation granted funds for the restoration. It was only possible because in Cairo one can still find master carpenters able to reproduce an enormous bay window composed of more than 6,000 turned-wood pieces (each one of which was individually crafted with a hand-held knife) and assemble it exactly as before.

There is an important constraint though. The buildings and objects that we try to preserve were often commissioned by mighty rulers and extremely rich people – their exceptional qualities are frequently the very reasons they have survived. The founders could afford the most expensive materials and the best craftsmanship available, while conservation typically has to be done within a limited budget and with economy in mind – not the least because in a city such as Cairo there are always so many other buildings that require attention.

I wrote a book, The Building Crafts in Cairo: A Living Tradition, which compares contemporary crafts in Cairo with descriptions from 1798-99 in the Description de l’Egypte by Napoleon Bonaparte’s scholars.

How did (and do) public buildings contribute to the fabric of Cairo?

Cairo has a long tradition of institutions and buildings dedicated to public services. In the ninth century the city had a great public hospital offering free healthcare based on the best medical knowledge of the day. Little remains of the original grand buildings of another hospital built by the Mamluk sultan al-Mansur Qalaun in the 1280s, but after more than 700 years, there is still a hospital in the same place.

Such institutions were supported by religious endowments (waqf in Arabic.) Religious establishments also supported numerous different charities. A particularly popular one distributed free drinking water from an underground cistern – welcome in the scorching Egyptian summer, in a city where water in wells was brackish and drinking water had to be purchased.

In Cairo, these public fountains were coupled with elementary schools offering free education to orphaned children. There were more than 300 such buildings in Cairo by the 1790s; many are architectural jewels. More than 70 have been preserved; I have directed conservation work in three.

There were also structures built specifically to offer free drinking water for animals, some of them as exquisitely decorated as any palace.

When thinking about public spaces and services in a traditional Middle Eastern city, one must remember the role played by neighbourhood mosques, which are focal points of community life. People come here to pray, but also to meet, exchange news, seek advice on family matters, or just rest in a peaceful, friendly place. When in 1999 a small community mosque collapsed next to a building that I was conserving, I was able to summon foreign aid funds for the rebuilding of this important focus of community life.

The firm has worked on a number of museums. Can you share a few golden rules of design in terms of a) displaying artefacts and b) best engaging the audiences?

What I have said about designing architecture in general is equally true in the museum design: there are no “rules of the thumb” that can be universally applied. Each collection, each exhibition is different. After all, this is why they exist: to present to the public something unique and extraordinary, or to condense into digestible form some aspects of history, social life, or natural environment that are important enough that people ought to know and understand them.

Two South African museums we saw during a short visit in 2012 serve as a good example: the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg and the Cradle of Humankind. Both are architecturally outstanding and present their contents in an innovative, engaging and inspiring way. However, the museums are also quite different, as much as their subject matter differs. To design a museum or exhibition one needs to understand what makes the collection special, why it is exhibited in the first place.

Museum displays are primarily visual experiences (sometimes auditory as well); words are secondary. No matter how well-intended and well-informed any accompanying text is, it is worthless if it is not legible and comprehensible (or if it is just too long!). It is essential when designing a museum display to put oneself in the position of a visitor.