Driven by an aim to upgrade built environments to a more human and engaging scale, and inspired by life and its challenges, architect Matthias Hollwich doesn’t let the grass grow under his feet. His CV is impressive, ranging from Architizer, a networking website for the architectural community, of which he is a co-founder, to Ageing in Africa, a retirement community for catholic priests in West Africa.

Hollwich has worked for OMA in Rotterdam, and Eisenman Architects and Diller & Scofdio in New York. In 2004 he edited UmBauhaus: Updating Modernism with Rainer Weisbach. In 2007 he founded HollwichKushner LLC (HWKN), an architecture and concept design firm, along with Marc Kushner in New York. Hollwich is currently a visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania where he’s started “New Ageing”, an international conference on ageing and architecture.

His work has been featured in, among others, Harvard Design Review and the New York Times. Some of HWKN’s more ambitious work includes a masterplan for the city of Dessau in Germany, residential work in New York City and, most recently, the first prize for the Windscraper Tower in Piraeus, Greece. The competition was sponsored by GreekArchitects.gr. HWKN’s winning proposal was characterised by a network of multi-purpose wind-generating “leaves” on the façade of the building.

The democratisation of public space: What does this mean to you and how do you ensure this through your designs?

Interesting question. As architects we always aim to make as much space available to the public as possible, make it as attractive as possible and as diverse as possible. But architects are also faced with political, financial and other limitations. This is why we also started Architizer, a social networking site centered around the architectural project. It aims to make architecture and the thoughts behind it more publicly accessible, resulting in having the general population demand better work.

You’re particularly concerned with “defamiliarising the ordinary”. What makes this a key motivation driving your designs, and what kind of impact is this kind of philosophy meant to have?

We are architects who do not embed our work in big theories. We are direct and intuitive. We love the banal and the common but within our design take it to another level. For example, for the Mini Rooftop design we took a simple hill and planted it on top of a building in New York. The location and the abstraction of the hill turned the ordinary into something extraordinary. Everyone can design a hill but through its architecturalisation and its insistence to remain so literal, it created something different. This difference is what made it memorable to visitors

Having worked all over the world, what are the specific challenges architecture faces in Africa?

I can’t speak in general terms but in our case the design work for our Ageing in Africa project in the Ivory Coast was one of the easiest, mostly owing to the fact that the client was curious, open and thought with common sense. We did not need a big marketing strategy or design philosophy. We were just asked to design the best we could for ageing priests and to embed it within the cultural context. The project is not built yet and the real challenges will arrive during construction, but we believe that the dedication we have experienced so far, these difficulties will also be manageable.

Tell us more about the Ageing in Africa and embedding architecture into the cultural context.

This will be the first dedicated retirement environment in West Africa. Everything we are doing is new and unknown but that also makes it so potent. The integration into the local culture is important wherever you design something for an ageing community. You do not want to force people into a new environment during a later age, you want to create something that allows for the most normal living conditions possible.

What are the architectural and social issues involved in designing for an ageing population?

It is actually quite simple. Design an environment everyone wants to live in but take into account that people lose mobility, social connectivity and might be sick to certain degrees. So it comes down to the idea that architecture needs to be better at becoming a “connector and enabler”, while also offering a good dose of convenience. In a study we came up with some points that should be taken into consideration when designing for the aged:

- Urban connection

- Urban invitation (attraction)

- Public interface

- Urban extension

- Inconvenient circulation

- Your own environment

- Body and mind extension

- The private garden

- The real outdoors

- Urban fusion

- Inspiring for all

Some say there exists a tension between the natural environment and the built environment. How do architects neutralise this tension and why is it an important obstacle to overcome?

Everything is nature. I believe even architecture is part of it. The only issue is if we continue to abuse our natural environment then we force nature to reinvent itself again, and then we need to ask if we will be part of this reinvention. To avoid this we have to integrate ourselves and our built environment into nature again or, with all the new opportunities in bioengineering, tune nature towards our needs.

Can/should architecture ever be viewed as a form of social science?

No, I do not think so but as architects we should take social science into account in our work.

Is architecture an art form? Said differently – does architecture have a higher purpose or is it design for the sake of design?

I believe that architecture has a higher purpose than just creating spaces for people. I believe that better design creates better environments, which helps to empower people in various ways. It is not an art but it is a profession with a clear purpose.

Does architecture have a role to play in promoting cultural richness and diversity?

I believe that every single human being should promote cultural richness and diversity including architects, who are able to contribute to it more easily.

The concept of “public life” seems to be a fashionable term at the moment. What is your interpretation of this concept and how does architecture make work of it?

The internet and social networking sites have taken a lot of activities "off the streets" so architecture that encourages this notion of “public life” or “public interactivity” is more important than ever. It’s about creating spaces that allow for accidental encounters and triggers new social interaction. That can happen in many different ways, and needs to be calibrated to the location, culture, and typology the architect is working on.

What inspires your work?

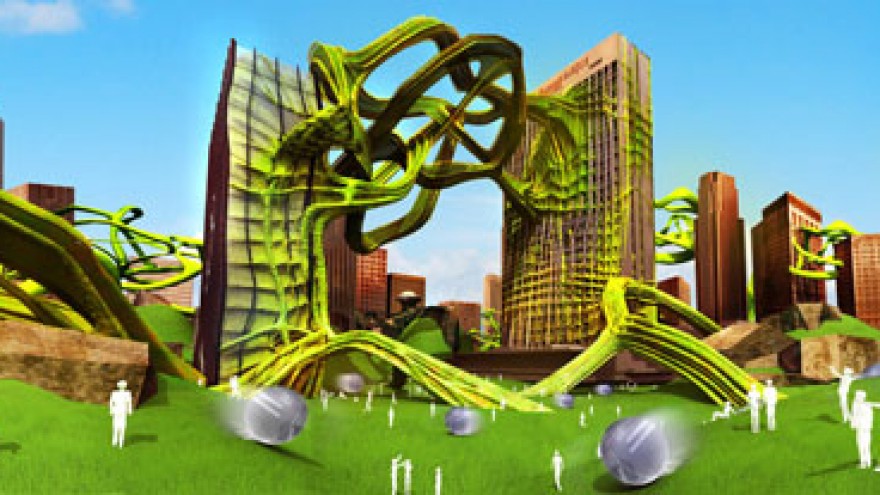

Life and the challenges it presents. In the past few years we explored the idea of ECONIC design, ecological icons that take the idea of sustainability to another level. Most inspirations came directly from Mother Nature. Recently we’ve been exploring “New Ageing”, looking at issue of ageing and embedding our design into a new understanding of how architecture interacts with humanity, heightened by challenges of ageing.

What does “sustainability” mean to you? Is it necessary to incorporate it into design?

I believe that we have to create projects that are as sustainable as possible. And it should not be an optional thing any longer. It needs to be the status quo. Our architectural infrastructure is consuming 40% of all energy in the world therefore our profession is the single most responsible profession for the pollution of our planet. Even car designers cause less damage.

Would you say that you have a specific design style?

I can’t say that we have a style but our work is becoming more and more recognisable. It comes more from the principles and issues that we explore. I would say that there is something undogmatic, playful and curious in our work. It might not always be the most beautiful piece of architecture but it will have character and integrity.

What makes a design good?

A client who stands behind a design and allows for an extended design development period. This allows a passion for detail to unfold and utilise its universal power.