First Published in

When Nthato Mathambo was 10 years old, he and his cousin decided to start rapping, but struggled to write lyrics. His cousin had Internet access way before anyone else in 1997. So the two of them looked up some lyrics on some obscure site, practiced it and then went to impress the kids at school. When the Wu Tang Clan played on the SABC a couple of months later, no one could comprehend why they were using Mathambo’s lyrics. “It was a whole new experience for us, because we didn’t know things could become that big,” Mathambo shakes his head.

More commonly known as Spoek, Mathambo is the MC who is burning up the European dance charts with his Sweat.X and Playdoe collaborations. With kids in the Ukraine singing along, one might think their success is built on the long-tail distribution channels of the Internet. “That’s a good question – I spend late nights wondering if we would have been as big without the Internet,” Mathambo quips.

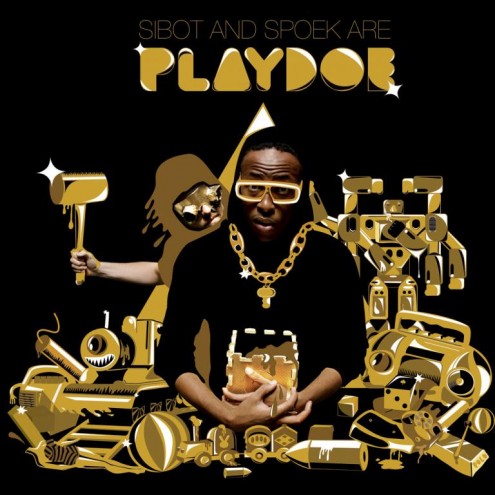

This slippery flippancy and seriousness is part of what makes Mathambo’s creative output so scorchingly original. The Guardian has called Playdoe: “Stupid fresh. It makes you want to go wicky-wicky and spin on your head”. While Vice magazine hailed Sweat.X as: “The last word in the whole hip-house/new rave/electrobooty funk thing that’s so new it hasn’t even happened yet.” Other youth culture magazines including Fader and Dazed and Confused have also sung their praises.

Playdoe is Mathambo’s collaboration with Sibot, one half of South African glitch-hop pioneers, the Real Estate Agents. The other half of the Real Estate Agents, Marcus Wormstorm, collaborates with Mathambo on Sweat.X. Arguably, Playdoe and Sweat.X can be distinguished by phat, asynchronous beats and playful lyrics, on the one hand, and frenetic, sexy pulsations and filthy lyrics on the other.

“It’s a new world man,” Mathambo chides. “People used to talk about genres, but how can you be genre-specific when you know everything? We’ve got so much information now; why not use it to make hybrids?” In the past, Mathambo has called the hybrid “future primitivism”, although he now brushes it off as a “three-year-old idea”.

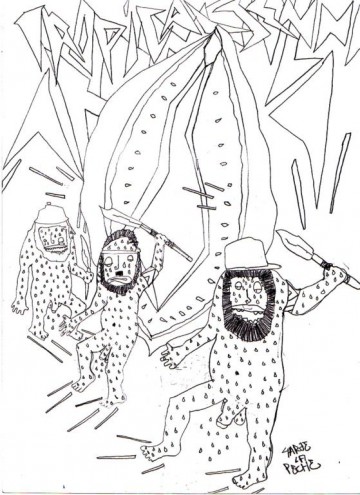

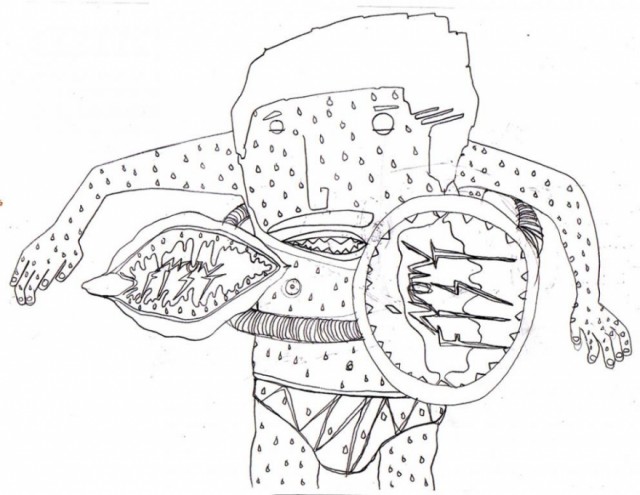

Capitulating, he tells me about a group of American girls that he and Wormstorm had seen in Cape Town. “They were big, hypersexual black girls who were dancing in a really uninhibited way with a real physical connection to the music, and all space and time ceased to exist – for everyone in the club, it effected everyone in the club,” he gets into the tale. “It felt like a really old way of enjoying bass music. So, we wanted to get people into those kinds of primitive frenzies of lust and love through progressive music. This [Future primitivism] also effected the images I started to create, which became about simple shapes, somewhat abstract, but still relating to the core of how people see things.”

But hey, back then, he was “just about pants and image”. Today, three years on, he says: “I used to be a rising phoenix messiah, but now I’m the loving father god.” (Yup, I’m already looking forward to interviewing him again in three years’ time.) He goes on dreamily: “Now the stuff that is coming out of South Africa has me properly excited. I think I’m moving into more of a role of cultural curator.”

This is where Mathambo’s more recent projects come to light. The newest is Moleke Mbembe, his collaboration with Richard the Third. “I’m getting to make the angsty beaty post-punk post-hip-hop electronic African-based stuff that I’ve been trying to do for the past seven years,” exclaims Mathambo. (“Moleke Mbembe” means “one that stops the flow of rivers” and refers to a mythical dinosaur that stops the flow of the Congo River.)

Besides then his Dirty Dirty club nights in Johannesburg, Mathambo also collaborates with Big Space on two projects – the Slush Puppy Kids and HIVIP. HIVIP is a DJ moniker under which the pair promote township techno. Not just DJ Mujava, but more than that, Mathambo insists: “He’s the one that has blown up overseas, but the reality is that the people who are popping here are Durban’s Finest, DJ Cleo and so on.”

But why HIVIP? Are they trying to be shocking? Mathambo sniggers – I so don’t get it. “We are the post-HIV scare generation and that, in everyone’s consciousness, is like Big Space says, ‘You’re rolling back every time you have sex.’ When I travel around the world, other countries do not have that on their minds at all. So on one hand, we’ve got this paranoia, but on the other hand, for kids who have come from single-parent homes and HIV deaths, there’s an intense celebratory vibe in our poorest communities, which is where the music HIVIP plays comes from. The music that comes out of these communities is of the most sophisticated technological level – HIVIP,” he explains.

Mathambo is assertive when he says “the idea of being ‘African’ is like trying to be ‘rock’n’roll’. It’s a bullshit idea.” He goes on: “I’ve grown up in South Africa and I am who I am through being here, part of which is through South Africa’s incessant programming of American content on TV.”

Mathambo is of a generation of South Africans whose lives did change with the end of apartheid. His first 10 years were spent in Soweto with his “BMX gang, going to church a lot and just being in a tight, vibrant community”. Then moving to Sandton with his family, his next eight years were spent in “suburban isolation”.

“Boredom forced me into playing Scrabble with myself and reading Choose-Your-Own-Adventure books; that’s probably when a lot of the writing and doodling came about,” he giggles. “I then got a bit too cool, a bit too young, and got into a whole bunch of trouble,” he refuses to expand but admits to submitting to “stark hermitude” as a result. In his late teens he started his own hip-hop magazine, which he made in Microsoft Publisher and copied on the school Photostat machine. His favourite novel is Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

“I do represent a chunk of ‘new’ South Africa, but definitely not a majority – not everyone moved to Sandton,” he confers. “There aren’t mass stereotypes in South Africa, there’s amazing individual stories. I would be dishonest if I tried to make my music that township or that ghetto. It just wouldn’t be me,” Mathambo is resolute.

“In terms of language, cultural practice and attitude to specific objects, if you were to look at the anthropology of culture, there’s so much other stuff than these old nationalities and races. We’re a little bit African as much as we’re a little bit rap, Sesame Street… everything,” the self-named “slippery post-apartheid glam rap prince” sums up his revisions on a tired view of ghettoised world culture.