First Published in

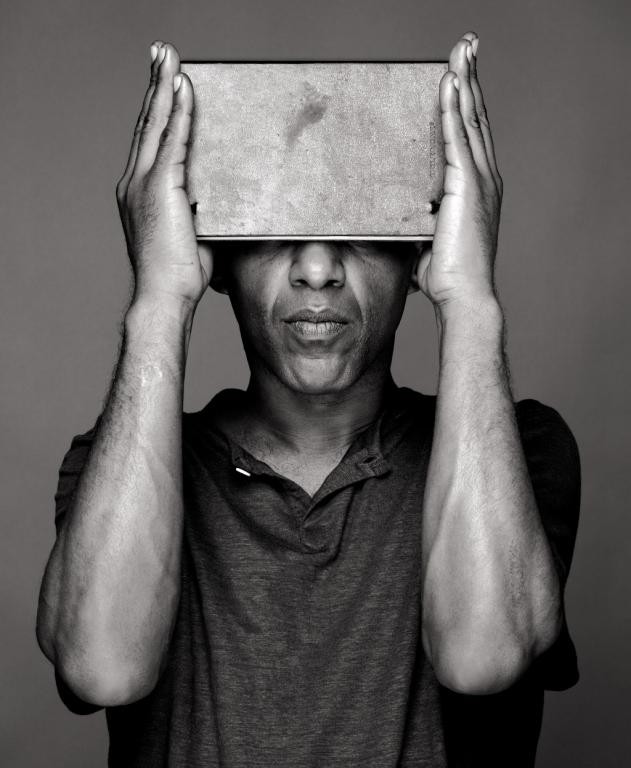

Lemn Sissay is a seasoned interviewee. At 21-years old, he published his debut collection of poetry to critical acclaim and, in as many years, has since published seven anthologies and four plays. Telly-watchers will recognise him as the youngest Grumpy Old Man on the first four seasons of the hit BBC sitcom, as well as the subject of the documentary Internal Flight. In 2007 he became artist-in-residence at the Southbank Centre. Sissay has been turning poems into landmarks since the late 1990s.

Yes, this is a rare poet who has had enough interlocution with the media to remember his own catchphrases, yawn at the boring questions, predict my oohs and aahs, laugh at his own pull quotes and interject himself with a shake of the head – “I can see the article now”, he mumbles to himself throughout the interview.

But where the reporter always gets hooked, he says, is on the subject of his gruelling childhood. “And who can blame them?” he shrugs off the stark tale of an Ethiopian student who lost her son after placing him in temporary foster care in the UK.

What happened was that the care worker renamed the infant Norman, after himself, and allowed a British family to legally adopt him. Religious zealots from Lancashire, the foster parents believed that God had sent “Norman”. When “Norman” was 11, the family came to believe that he was evil and was promptly returned to the foster care system to spend the next seven years of his life in-between children’s homes. The first time he met another black person was when he was 14. He reclaimed his name, Lemn Sissay, at age 18.

“It was an emotionally violent existence and I had to find a way of interpreting the world into a place without violence, so that I could see wonder, because I deserved to see wonder,” Sissay explains his turn to writing.

Since he was 18, however, Sissay knew that he had to find his family. “It’s become the narrative of my adult life,” he smirks at what has become one of his catchphrases. After finding every last one of them – from Ethiopian mother and dead Eritrean father to siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents – by the age of 32, he coined another of his catchphrases: “I now have a dysfunctional family like everyone else!”

Sissay’s humour is so self-aware, so to-the-bone and so subconscious, it is often intestinal. “You know like a child who is laughing and then is kicked. They don’t understand the pain, but they do understand that they were happy. So their relation to laughter is really in contrast to the punch. But we all deserve to laugh. And… I’ve never said this before…” He breathes in: “Laughter is a shortterm hit, not the answer. Only a fool thinks it is!”

He beams, shakes his head at himself and rambles on: “The poems and writing for me are totally beyond my narrative. It just happens that I was lucky enough to find this great ship that can carry pretty much anything. There are small quarters on the ship that is my family story and every time I speak to a journalist, they want to go to that room. That’s okay.”

Turning to gloat, he says: “But actually, I’m rocking out to sea, riding the waves, putting up the sails and fishing.” Gloating because now, in his early forties, Sissay has come to realise: “My poems are my family.”

He lowers his voice: “I found my family all over the world, my actual physical blood relatives. But my poetry has been with me for longer. So when there wasn’t family, there was poetry. And to be honest, there’s more truth in my poems than I will ever be able to extract from my family.”

Imitating Dr Evil, he raises his eyebrows a couple of times. Sissay’s incomparable ability to wear fragility as armour is dumbfounding. We’re sitting in a coffee shop off Long Street in Cape Town, shortly after the Africa Centre’s Badilisha Poetry X-change, and Sissay flags down a passer-by only to find that he’d mistaken them for someone else.

Electrifying audiences with a mind that runs faster than his tongue, a few weeks later, Sissay headlined the Grahamstown National Arts Festival and went on for a run at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg. None of these are Sissay’s first visits to South Africa. He has been visiting regularly since 1994 when he participated in a Robben Island project. Of the country, he says: “I always find the greatest communities in the world have a very complex set of arteries surrounding their hearts.”

Similarly for this “first generation Ethiopian Eritrean Brit”, as he calls himself, the question of identity is like the colour of the sky. “It’s like saying the sky is blue, but it’s not actually, it’s a reflection of the sea. So you could say the sky is blue, the sky is invisible, the sky is grey… it’s all of those things. Stories aren’t simple, which is why we have creatives. And we’re all creatives,” he reasons.

Going on, he insists that “creativity is an integral part of society, it’s not on the periphery but at the centre”. This is the power of the arts for Sissay, beyond the needs for context, narrative or legacy, he vehemently continues: “We have never lived without art, yet society perceives art to be an addition to life and the fact is, if you look at our religions, they’re all told through great stories, literature and art – physical art. The artist is often employed to carry the message, but sometimes I wonder, isn’t the artist itself the message?”

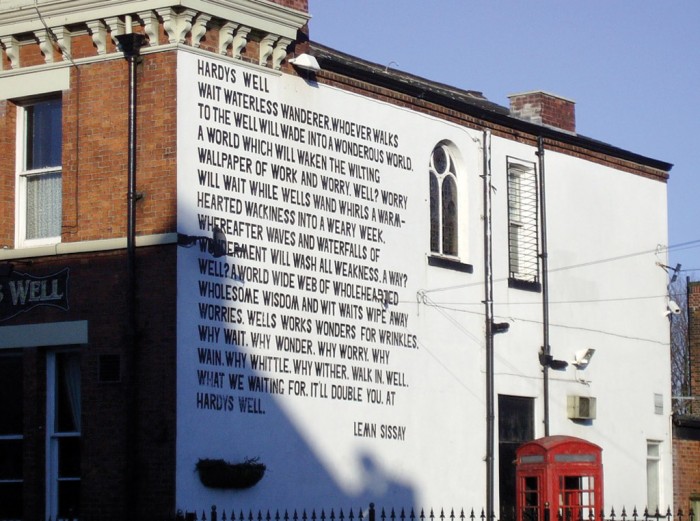

Taken from a man who has transformed poems into physical landmarks throughout the city of Manchester, now infiltrating London, such talk is only mildly alchemical. What is gratifying about his poetic interventions is that, as Sissay says, “The beauty of a landmark, is it’s not a landmark by you, it’s by other people. You can’t build a landmark, people have to choose it.”

The first landmark was the result of a taunt from some mates in a local pub and Sissay decided to “show them”, resulting in Hardy’s Well being branded on the eponymous pub. Since then he has inscribed Rain above the Gemini Take Away, Flags on the cobblestones along Tib Street and Catching Numbers in the Shude Hill Bus Station, all in Manchester. Last year, he unveiled The Gilt of Cain in London. This collaboration with sculptor Michael Visocchi commemorates the bicentenary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade.

“The beauty of a poem in the landscape is that you suddenly start to notice a building that you always pass without noticing. It’s not about finding the biggest spire, but about discovering your neighbourhood and bringing people to an environment that they might not have discovered by their own eyes and ears,” says Sissay. He shrugs: “The poems are architecture.”

Visible creativity is an urgent message for Sissay, as he reemphasises: “There is a structure and anarchy that an artist acknowledges and we need that, even if a lot of the time we are afraid of seeing it.”

“Why are we scared?” I ask rhetorically.

But this man of woven words has an answer: “Because art has always gotten to the truth of the matter and we have been taught to be frightened of the truth of the matter.”

ARCHITECTURE

Each cloud wants to be a storm

My tap water wants to be a river

Each match wants to be an explosive

Each reflection wants to be real

Each joker wants to be a comedian

Each breeze wants to be a hurricane

Each drizzled rain wants to be torrential

Each laugh from the throat wants to burst from the belly

Each yawn wants to hug the sky

Each kiss wants to penetrate

Each handshake wants to be a warm embrace

Don’t you see how close we are to crashes and confusion,

Tempests and terror, Mayhem and madness,

and All things out of control

Each melting Icecube wants to be a glazier

Each wave wants to be the smooth stroke of a forehead

Each cry wants to be a scream

Each carefully pressed suit wants to be creased

Each midnight frost wants to be a snow drift

Each mother wants to be a friend

Each night time wants to strangle the day

Each wave wants to be tidal

Each subtext wants to be a title

Each winter wants to be the big freeze

Each summer wants to be a drought

Each polite disagreement wants to be a vicious denial

Each diplomatic smile wants to be a one fingered tribute to tact

Don’t you see how close we are to crashes and confusion,

Tempests and terror, Mayhem and madness,

and All things out of control

Keep telling yourself.

You’ve got it covered.

REMEMBER HOW WE FORGOT

We don’t cram around the radio anymore

We have arrived at the multidimensional war

Where diplomats chew it up spew it up

And we stand like orphans with empty cups

‘There will be no peace’ the press release

Said that war is on the increase

We are being soaked with a potion

Massaged with lotion to calm the commotion

That hides in the embers of the fire

There’s nothing as quick as a liar

Don’t you learn your lesson

Are you so effervescent that

When they say day is day and its dark in your window

You say ‘ok’ and listen more tomorrow?

Seems you heard the trigger word

Are you space to be replaced – dreams defaced

Heavy questions quickly sink

Leaving no trace – a spiked drink

What kind of trip are you on

Don’t you remember the last one?

Remember how we forgot about Vietnam,

Afghanistan, will you fall or stand

For a dream you haven’t seen?

I’m afraid you will, you have taken the pill

And you are totally stoned on war.

Media Hype and the slogans they write

Is that all it takes to set you alight

There’s nothing better than a doped up mind

For a young unemployed man to sign up

Figures go down young men sign up

What better when losing votes than to erupt

Into the uniting sound of war fever

“We need unity now – more than ever…

We shall only attack to defend…”

Paranoia infiltrates…

“Are you one of us or one of them!”

Slogans fall like hard rain as government calls

For someone somewhere in some country

That is suddenly so vital to our history

More than ever we should pull together

These are the days of stormy weather

Patriots show faces, nationalists recruit places

As the fear of the foreigner rises

The race attack count arises

Victims of the small island mentality

England is no mother country

He holds the fear of the Awakening

Of his shivering shores breaking

Like the those in the Middle East did

When he raped it –

will you take it – take this, without question

Fall in line with the press poet or politician

Remember how we forgot about Vietnam,

Afghanistan. Will you fall or stand

For a dream you haven’t seen.

I’m afraid you will, you’ve taken the pill

You are totally stoned on war.