In the national pavilion exhibition, titled kith and kin, First Nations artist Archie Moore confronts the ongoing legacies of Australia’s colonial history with a vast hand-drawn genealogical chart. With it, Moore became the first Australian artist to win the prestigious Golden Lion for Best National Participation, at La Biennale de Venezia 2024.

On view until 24 November 2024, kith and kin transforms the Australian pavilion with the expansive, genealogical chart spanning 65 000+ years. Drawing on his Kamilaroi, Bigambul, British and Scottish heritage, the installation embodies Moore’s enduring exploration of history and identity. The major work brings awareness to First Nations kinship in the face of systemic injustices since the British invasion in 1770.

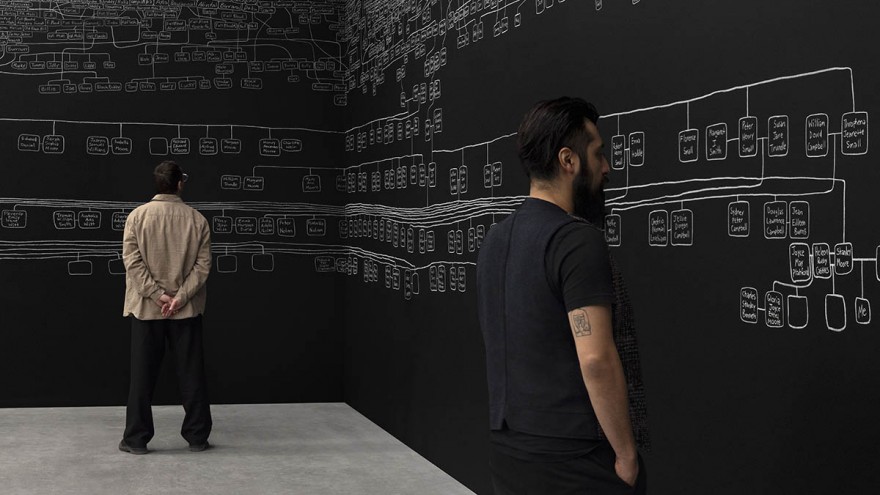

Hand-drawn in white chalk, the chart unfolds across the pavilion’s five-metre-high black walls that run 60 metres in length, illustrating Moore’s lineage stretching back more than 2 400 generations. Derived from the artist’s research with family, community and archivists, this intricate map of relations reflects the unique familial structures of First Nations Australians that include all living things and affirms their status as some of the longest-continuous living cultures in the world. In the First Nations Australian understanding of time, the past, present and future are co-present. By placing tens of thousands of years of kin on a single continuum, Moore makes this notion visible to audiences.

The chart also represents the decline in First Nations Australian languages and dialects. Over 254 years, the numbers have plummeted from as many as 700 to around 160, due to prohibitions on First language use, land dispossession and the killing of kin in colonial warfare. Countering this, Moore enacts language maintenance through his use of Gamilaraay (the Kamilaroi nation’s language) and Bigambul kinship terms.

Curator Ellie Buttrose said of the exhibition: ‘kith and kin reaches so far back into time that it includes the common ancestors of every human and all living entities — a timely reminder that we all have kinship responsibilities to one another. The simultaneity of past, present and future underpins the First Nations Australian understanding of time. By placing 65 000+ years of family on a single continuum, kith and kin immerses audiences in the co-presence of the ancestors and coexistence of time — by doing so Archie generously enfolds each of us into the everywhen.’

At the centre of the pavilion lies a reflective pool with more than 500 document stacks suspended above in an inquiry into the injustices still faced by First Nations peoples today. Despite First Nations Australians being just 3,8% of Australia’s population, they account for 33% of its prison population, making them among the most incarcerated people globally.

‘Surrounded by the limitless family tree, viewers are reminded that the reports do not represent nameless statistics; rather, they are children, siblings, cousins, parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents and great-grandparents,’ explains Creative Australia, the country's official arts council.

READ MORE