Part of the Project

Blackness has throughout history taken on the burden of colonisation and then later, the burden of the post-colonial idea of what black bodies and in particular, black women represent. As more and more women of colour fight for self-determination, we see a shift in the narrative of black bodies as sufferers, workers, toilers, and victims. For Johannesburg-based artist Rendani Nemakhavhani, black women are more than struggle, “black women are power.” In her photo series, The Honey, Nemakhavhani teams up with photographer Kgomotso Neto Tleane to document Honey, a black woman whose narrative is created about blackness that is rarely represented on commercial platforms.

“She is a black girl who doesn't conform to a fixed identity. She is power, she is a part of me,” explains Nemakhavhani. “I used myself for this very purpose.”

I believe that as creatives we have a handful of power that we can use like in this instance to create our own narratives.

Honey’s story is told in four chapters. Nemakhavhani explains that in these chapters, Honey is whoever she wants to be. “In the series we show this through the different attires Honey wears as well as the different roles she plays in the different chapters.”

In chapter one, Honey is introduced brandishing a sjambok, a traditional leather whip. In chapter two, Nemakhavhani explores the dynamics of black hair. “Honey has an undercut as well as bob braids. She models around in a salon in Soweto. In this part of the series we basically are showing this sanctuary that has been a part of many women’s lives,” she explains.

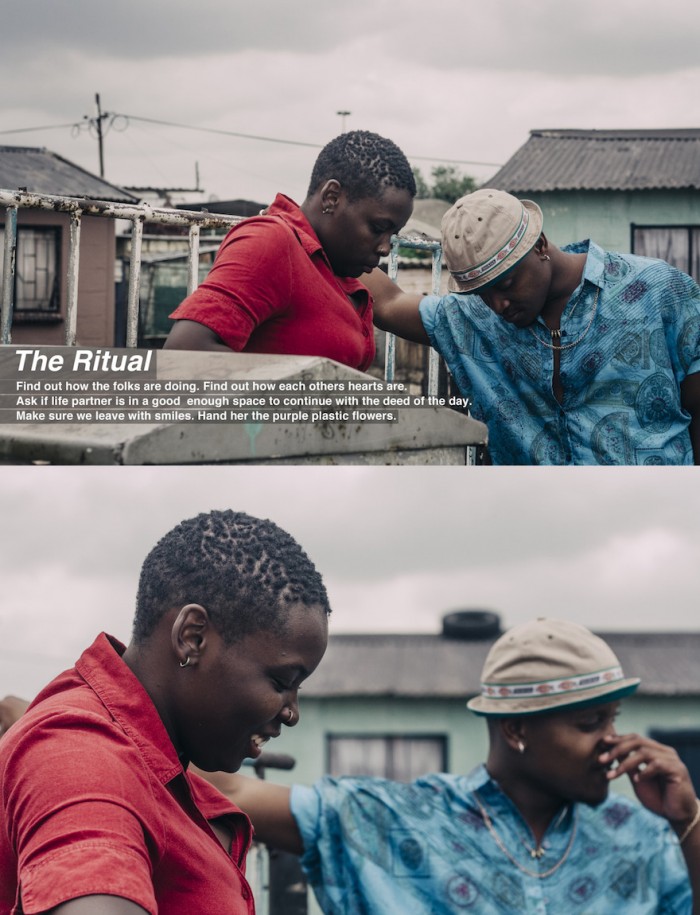

Chapter three is an ode to Yizo-Yizo, a controversial South African drama series of the late 1990s. “In chapter three we introduce Honey's boyfriend, Gavini. They are both thugs and are waiting on a cash drop,” says Nemakhavhani. “We replicated some of the scenes from the series. This is the chapter that got the most attention.”

In chapter four, the Gavini proposes to Honey, he also leaves the series in this chapter. The home the two are pictured in is nostalgic in that it mirrors the home’s where a number of black people grew up.

“Many black people who grew up in a house like this were familiar with the overall look and feel,” Nemakhavhani says. “It's always awesome when the responses are related to nostalgia.”

Nemakhavhani believes her project is able to bridge the gap, and go further than exclusion and status.

“I believe that if you're going to represent a black woman in particular you need to give solid context, that makes relatable sense,” she says. “So you serve the good and the bad.

We're dynamic man! Being a black girl from the hood doesn't mean that you're going to be poor or “uncultured” for the rest of your life.

Nemakhavhani hopes to turn her project into a photobook: “It's cool when we can upload things onto the net, but I feel it's better when products can become tangible.”