Graphic Design: Now in Production is one of the largest graphic design exhibitions in recent years.

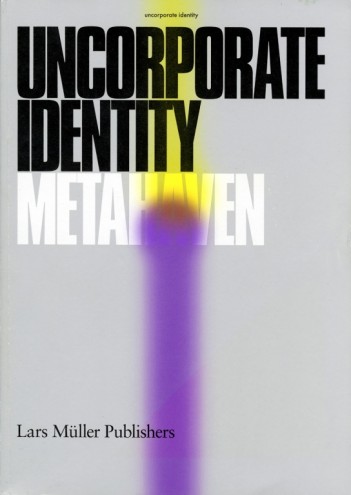

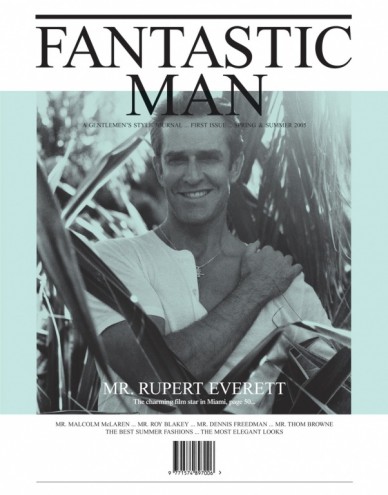

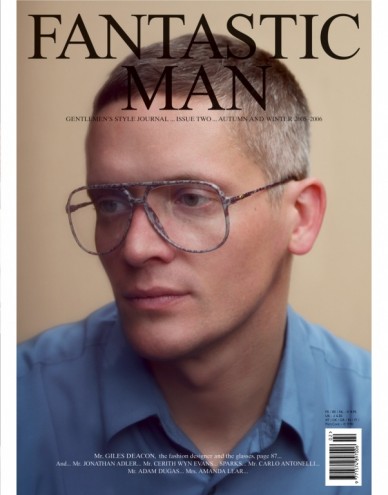

Taking place at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from 22 October 2011 to 22 January 2012, Now in Production presents some of the best graphic design work from the year 2000 to now, including magazines, posters, books, information design, branding and identity, typography and film.

Visitors to the exhibition can expect to be wowed by the work of, among others, Stefan Sagmeister, James Victore, Marian Bantjes and Maureen Mooren.

The event, which was co-organised by the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, also explores how the role of the designer can shifted to that of a designer-maker.

Exhibition curator Andrew Blauvelt tells us more about Graphic Design: Now in Production.

What was the motivation for the show?

There has not been a major museum exhibition of contemporary graphic design in the US in decades and it seemed time for one. The field has undergone so much change in just the last decade that it seemed ready for some kind of summation. The curatorial challenge was to find a focus for such a broad activity. One key aspect of the transformation of graphic design was the idea that it had moved from a relatively obscure profession to the public to a widely deployed tool, something available to a much larger group of people than ever before.

What is the new role of the graphic designer in the age of social media and creative user software?

Graphic designers have a particular challenge to their practice and role because the software, tools, and systems for communication are more widely known and available now, both to them and to anyone. There's no real gatekeeping to the practice, unlike the legalities of architecture or the complexities of product design. I think this situation makes the field of practice more interesting. After all, everyone in school learns to write but not everyone calls themself a writer. This democratisation opens the profession and practice up rather than closing it down.

To prove their value, graphic designers have expanded their knowledge base and the kinds of processes they use to solve problems. They become more expert with the software. They even create new software and revive old tools and methods.

How exactly has social media affected the design profession and what are the consequences of this?

Social media creates a kind of "third space," a public and semi-public realm that bridges the individual, the community, and the world of commerce. There is a lot of chatter going on, but also a lot of listening and monitoring, and various attempts at steering or leading the conversation by designers, marketers, and others involved in communications. For example, since branding campaigns are now public events, the reactions to these are much more instantaneous and potentially volatile than before. So, the Gap rebrands itself. The Twittersphere erupts in disgust and the project is cancelled. Pepsi wants to project an image of social good and uses crowdsourcing methods to fund worthy projects.

There's been mention of designers in a new role as producers: What are the implications of this?

The idea of the designer as producer is possible today because the tools - devices, distribution systems, open platforms, software, etc - are more readily available and accessible. It is witnessed in the graphic designer who has traditionally helped business owners create brands and products and use those skills to make their own goods and services. You can see it in the possibilities of self-publishing, print-on-demand and publish-on-demand systems that are now available or in designers who are taking on expanded roles as authors and editors in the publishing process. It is certainly prevalent in the phenomenon of font design, in which software made the mysterious world of type design more readily available. The digital type foundry is the new cottage industry.

The implication is that role and practice of graphic design has expanded with new opportunities for designers to take on more and different activities. And as design becomes more readily available and understood beyond its professional core, more non-professionals are creating designs.

What are some of your favourite works on display, and why?

With more than 500 objects, it's kind of hard to narrow things down. There are some projects with which visitors can interact that raises expectations about what graphic design is and can be. On the other hand, there are so many beautiful books being produced, which flies in the face of expectations about the death of print. You also see a passion about the process of making and about content. It's a blend of technology and technique, craft and concept.

What were some of the challenges you faced in curating this exhibition?

Dealing with a field that is so broad and always seems to be changing is a great challenge, a moving target. It became nearly impossible to cover new areas of practice such as social design and service design, which seemed to demand a different exhibition format or display strategy. We selected some other curators to help us organise the selections. This was an expression of our interest in the amateur-expert, or pro-am curator (the professional-amatuer - passionate knowledgable people who know so much about a particular practice).

Was it a conscious decision to make the exhibition so big, or is it simply the way it evolved?

It evolved that way from the beginning. Graphic design is kind of difficult to define for the public. At first we thought it could contain whatever projects fit the thesis without worrying about specific genres. However, the public knows graphic design through its varied genres: posters, magazines, books, fonts, logos, etc. We thought it best to start with this familiarity and then expand the genre and unsettle expectations.

How should graphic designers be responding to social media and user-generated content?

The show basically redefines graphic design as a kind of tool, an instrument now available to many people, non-traditional designers and those who are professionally trained.

This democratisation or access to tools challenges graphic designers to rethink their relationship to things like craft and labor, managerial and conceptual activities. This is very exciting time for the field rather something to think of as some kind of loss. It's messy, but so is nearly anything open-ended. Social media networks connect people and so designers should be excited about how they can use this new tool to help them at all stages of the design process, not just in conventional terms of an audience to whom you pitch messages.

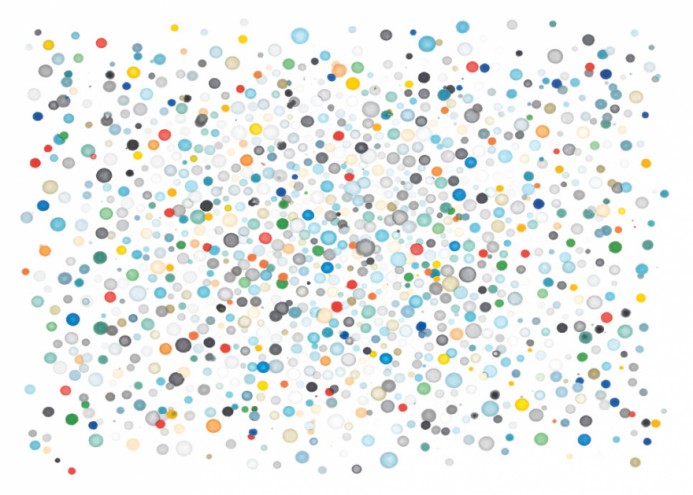

User-generated content is perhaps the most exciting development. It up-ends the traditional notion of a design as a fixed and finished entity to one that is, by design, incomplete.

Design can expand to include the design of systems and processes that encompass content created by others.