First Published in

Although David Boira and I are both trained architects, through our studio, Commonwealth, we have become particularly interested in working at a scale that is smaller than that of buildings - porcelains, interior elements and, most importantly to us for now, furniture.

Working at a scale smaller than that of building has given us greater freedom to be more expressive and experimental in our work. When you work in architecture, you are constantly bound by some very difficult constraints. The finances are large, liability always looms in the background and failure has so many repercussions that it is hard to view as “tolerable”. Building can be a very difficult medium for young architects to experiment within.

To date, much of the work we have designed has been art and furniture exhibited in galleries, but as our portfolio expands, so too does the range of commissions. We’ve recently begun working on the stage and prop design of a visually intense music video, which has brought us a whole new visual perspective of what we are pursuing.

By scaling down, and working on a wide range of smaller projects, all of which are intimately instructive to the broad field of architecture, we’ve had the chance to investigate the finest of details that are at the core of design generally, without sacrificing a sense of relative speed within projects. That is very important when you

are working in an experimental way. Experiment is really necessary for young offices. I think it is the only way you can really discover what you uniquely have to offer.

When we say we are experimental and research driven, it doesn’t mean we have any sort of disdain for client requests or problem solving. On the contrary! The fact that design is something that must, by its very definition, be involved with cultural movements and matters of function gives the field an incredible richness – something that has always been very important to us.

However, I think it is also true that design suffers from a self-imposed expectation to be modest, democratic and anonymous – unlike the field of art. Carrying that kind of burden isn’t always great for the end products.

How can I further explain this thought? I think there is certainly a shift happening in design where the idea of “function” is expanding. The classic paradigms of design as client-oriented “problem-solver” has become so cunning, so anonymous and so well served via the global markets of IKEA and the like, that there is a great desire from both the designers and the clients to produce something that speaks to a broader definition of need and perhaps a more irregular idea of who the consumer is.

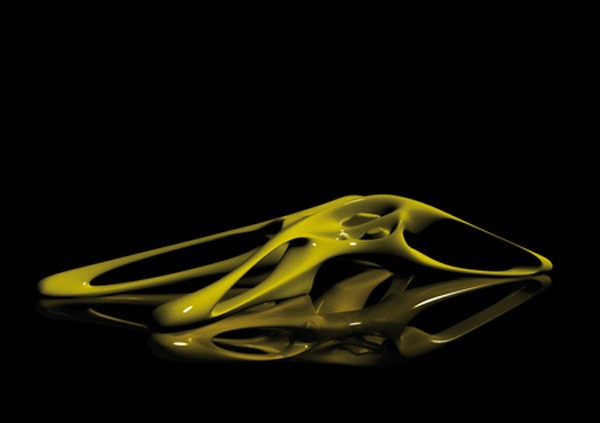

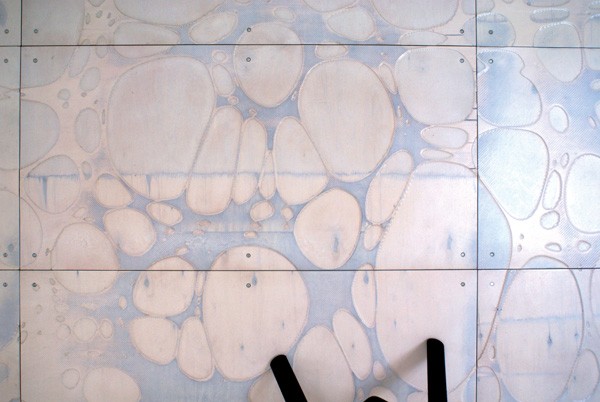

Some of the most exciting work coming out of design right now is work that is not naïve about the sophistication of 21st century orders and tools. But what is very important here, as artists, innovators and architects, is to see what is missing from these very sophisticated systems. For us, one of the things we are trying to re-engage through digitally driven means, is a sense of historical continuum, as well as a very supple and tactile sense of beauty.

Nearly all our work is dependent at some point on digital techniques for the making of form, and for the driving of material manipulations. But what really excites us is the use of these tools as a means of trying to activate timeless issues in design. For example, matters of proportion, balance and beautifully unexpected results. These are very humane issues that have always been at the core of design.

Those practicing architecture have in many ways become disconnected from the materials and products specified within designs. Broadly, it is an outgrowth of a culture that thinks that “gentlemen don’t work with their hands” – a class divide that has deep roots and effects in many fields beyond architecture.

Running a studio and a workshop for the prototyping of ideas has been enormously instructive for us – I couldn’t believe the first time I tried to lift a large sheet of glass. I really had no clue what that meant in terms of the very crude material properties of its weight and strength.

What has been valuable for us is not simply a closer interface with basic processes at the root of industrial production but, more importantly, the chance to develop a way of thinking that is deeply connected to the way you make things. This means that sometimes intellect is not at the forefront. At least it doesn’t need to be the sole engine behind a project. Much of our work embodies many ideas, but most of it couldn’t be described as purely conceptual. Often it is in the form, material and exquisite resolution of detail that the successes or failures lie.

I think this is reflective of a larger shift in thinking about design. A couple of digitally driven production machines have become much more accessible to small studios – machines such as three axis mills and SLA rapid prototyping machines. Many of the architecture and design schools have been investing in these machines over the past five years, as have small studios such as ours. It is a very interesting moment, because the true potential within these processes of production is not merely as an agent of efficiency. Of course most of these machines are employed as a means of making what was once done manually faster, which is a real shame, and somewhat of a waste.

Instead, there is a deeper attitude one can develop here – and that is to treat this type of digitally-engaged design as an entirely new medium, one which can only be explored through both a very instinctual and visceral ability to manipulate digital modelling software, coupled with regular experiments with the output machines and materials that will be used for the production of these pieces. If you take the view that you are either a “gentleman, who doesn’t use his hands” or a “digital fabricator who doesn’t have time or talent to think through what new attitudes and emotions are possible now in design”, then you can’t really do anything refreshing with these new tools or processes.

However if your goal, as is ours, is to really engage with the digital-driven as an entirely different medium – materially, aesthetically and spatially – then an intuitive understanding of machine-language in some kind of intimate way is absolutely fundamental, as is an understanding of other kinds of material production.

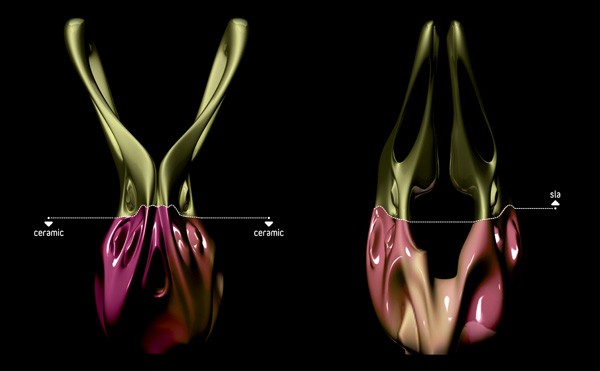

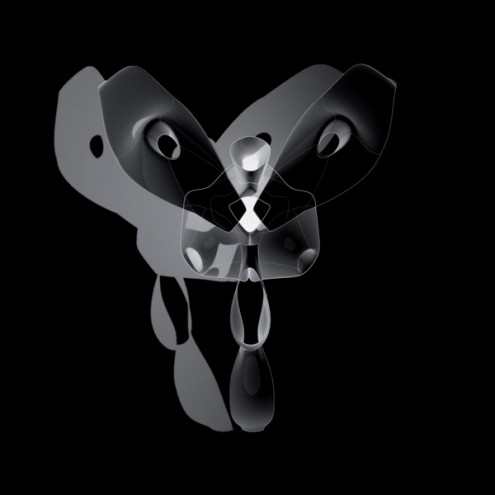

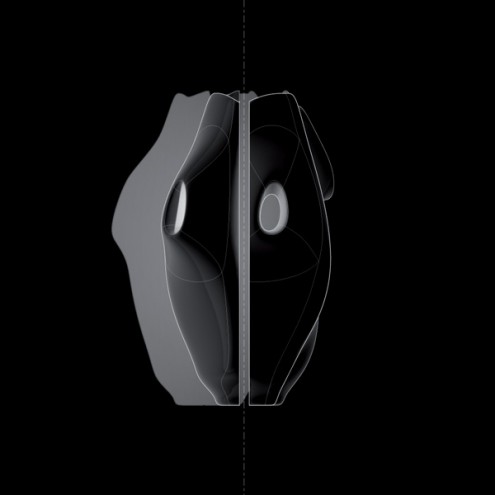

We are working on a project right now, provisionally called Slamica. For this, we are creating a series of vases that have two parts within them – an upper support for flowers and a bottom vessel for holding water.

The upper half is made of rapid prototyped SLA plastics, which are robotically printed and very exact in their making. When we model it digitally, we specify it to be of a certain circumference and overall form. When it comes back from the rapid prototyping manufacturer, it is exactly that size and dimension. The material is very stable, and doesn’t shift over time.

The bottom half, on the other hand, is cast from a rapid prototyped part and ultimately translated into porcelain – a material that shrinks by 15% in the firing process. Not only does it shrink, but the material distorts in a non-uniform manner making it difficult to connect the regularised top and the slightly irregular bottom.

It is this very moment of disjunction, however, that is illuminating, since it is through contrasts and juxtapositions of traditions and tools that we can see each technique for what it is most clearly. As such, the real relevance and promise of this playful and experimental way of making, is that it is the same language that is used to drive all kinds of contemporary industrial production. If you can learn to speak it here, you will have a greater fluency with the world of production everywhere. This is why we feel so lucky to be working at a time when it is feasible to invite a small corner of the industrial factory into our little Brooklyn studio.

We think it is important not to be precious, or reactionary Luddites or generally opposed to technological progress and change. Yet there is a certain kind of humanity that clearly needs to be restored into the products we surround ourselves with. I think this goes a long way to explain contemporary design’s current obsession with pre-industrial crafts and the art market. The great challenge we see is to find a means of embracing technological sophistication that is available, while manipulating it in such a way that you are able to produce work that feels wet, rhythmic and most freshly human.