DNA recovery is one of the most crucial factors in catching perpetrators of rape and sexual violence. A team of researchers at the University of Leicester are designing and testing a self-examination kit for victims of rape to remove the need for access to a medical facility or trained professional.

There are a number of factors at play here. Sexual violence and rape are used during times of war, oppression and to seek control over another in any environment. People who live in rural communities with little access to healthcare or a medical professional are the most at risk: This includes everything from their sexual health, to identifying the perpetrator and seeking psychological help after the attack.

There is also a stigma attached to a rape survivor. At the same time cases of sexual violence are frequently under-reported and victims rarely get justice. Those who do seek medical help often sit through invasive procedures by predominantly male doctors.

Internationally, we’re currently observing 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence against women and girls. It’s a huge social and global health challenge that affects more than one third of all women in the world.

DNA profiling is one way to address this crime. But in times of war, poverty and stigma, DNA often can’t be recovered.

Kenya is a country experiencing some of these problems. University of Leicester researchers Charlotte R King and Laura Stevens noted that prosecution levels for sexual violence in the country are extremely low.

“While 14 per cent of Kenyan women aged between 15 and 49 have experienced sexual violence at least once in their lifetime, very few cases get reported to authorities or go to court,” they say. “We learned from the Nairobi Women’s Hospital that fewer than 10 per cent of the 4000 rape cases reported were to the police.”

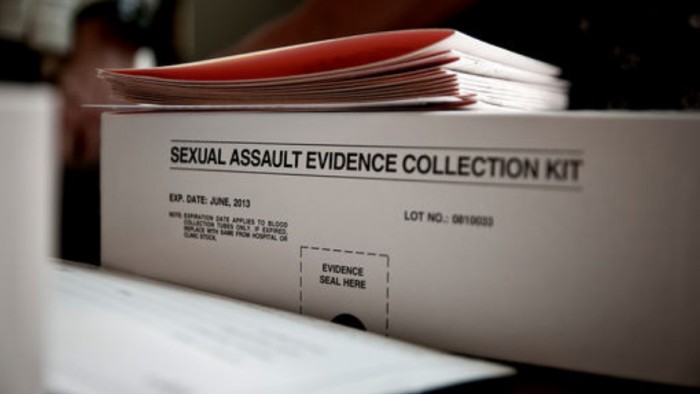

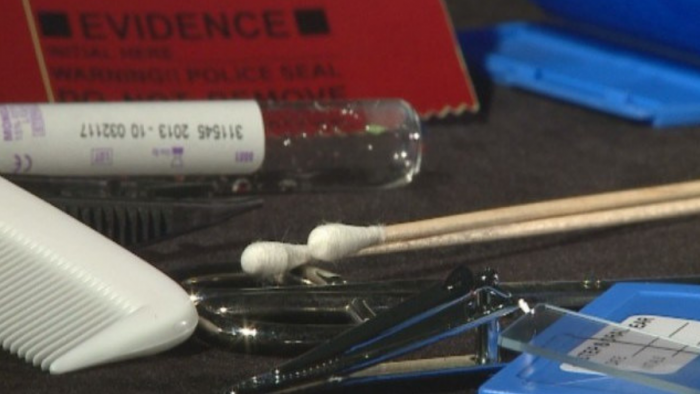

One of the projects that they believe will alleviate this problem is a self-administered, intimate DNA swab. Their work challenges the assumption that women must have intimate DNA swabs taken by a medical professional.

After conducting a proof of concept study with heterosexual couples, the research team found that women can collect DNA themselves after sexual violence.

“We have discussed this approach with stakeholders from across Kenya’s criminal justice sector. It is clear from these engagements that there is a significant need for such swabs, and for other ways of collecting DNA,” adds the team.

The initial design, while still under development, is much like a tampon. The researchers say that the swab must be comfortable to use, safe for the user and include instructions that are easy to follow.

“We will use a specially designed applicator, to reduce the risk of contamination, and tamper-proof packaging to meet international criminal justice system standards,” they say.

“The self-administered DNA kit we’re designing would make it possible to obtain valuable DNA evidence when there are no other means of doing so.”

We’re always on the lookout for design that improves the lives of people, challenges stigma and goes against preconceived notions. It’s true that the development of a self-administered rape kit is a valuable resource, especially in countries where war, poverty and stigma are rife.

But, as we globally observe the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence, the question must be asked: When will innovation, design and creativity focus its energies on the perpetrator? How could we flip the lid on the way we create solutions that address sexual violence by putting the cause at the centre of redesign?

If you have a project or opinion that speaks to this question, hit us up at editorial(@)designindaba.com

For now, here are more ways women try not to be raped

3600 panties focus attention on South Africa’s rape crisis

Kenyan grannies learn karate to fend off would-be attackers

Israeli student designs medieval-style chainmail for urban wearers

The Fearless Collective fights gender-based violence with unique murals