Space exploration seems out of touch when compared to the problems of the average person. Why the focus on the cosmos when we have problems that need solving right here on Earth? Researchers at Stanford University in the United States are working to integrate these needs by launching satellites that serve an agricultural purpose.

The study was authored by Marshall Burke, an assistant professor of Earth system science at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, and David Lobell, an associate professor of Earth system science. It could help estimate how well farms are doing and test the viability of intervention strategies in poor regions of the world where data are currently extremely scarce.

“Improving agricultural productivity is going to be one of the main ways to reduce hunger and improve livelihoods in poor parts of the world,” said Burke. “But to improve agricultural productivity, we first have to measure it, and unfortunately this isn’t done on most farms around the world.”

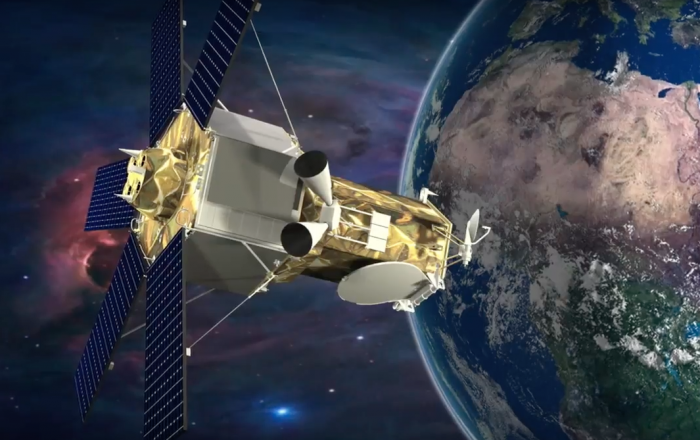

The measuring, according to Burke and Lobell, could be conducted by Earth-orbiting satellites. While the tech has been around for years, advancements have seen these satellites shrink in size and improve in image resolution, making the latest models better equipped than their predecessors. According to Stanford, there are there are several companies competing to launch shoebox-sized satellites that take high-resolution images of Earth.

“You can get lots of them up there, all capturing very small parts of the land surface at very high resolution,” explain Lobell. “Any one satellite doesn’t give you very much information, but the constellation of them actually means that you’re covering most of the world at very high resolution and at very low cost. That’s something we never really had even a few years ago.”

Burke and Lobell tested their theories on an area in western Kenya where there are a lot of smallholder farmers that grow maize, or corn, on small, half-acre or one-acre lots. They found that were able to make fairly accurate predictions. The two plan to scale up their project and test their approach across more of Africa.

“Our aspiration is to make accurate seasonal predictions of agricultural productivity for every corner of sub-Saharan Africa,” Burke said. “Our hope is that this approach we’ve developed using satellites could allow a huge leap in in our ability to understand and improve agricultural productivity in poor parts of the world.”