From the Series

First Published in

“For many people designing food is about the appearance of the food – the outside and shape. There’s a big gap between the designers who design shapes and chefs who design tastes. For me, I try to cross over these two things, but it’s not only the shape and taste, but also the story behind the food,” says Dutch food designer Marije Vogelzang, due to speak at Design Indaba 2008.

In fact, Vogelzang prefers to be called an “eating designer”, designing the entire experience into an event that challenges our preconceptions about food. With her strong emphasis on the context of eating, as well as addressing the psychological and social associations of food, an “eating designer” does seem like a more appropriate description.

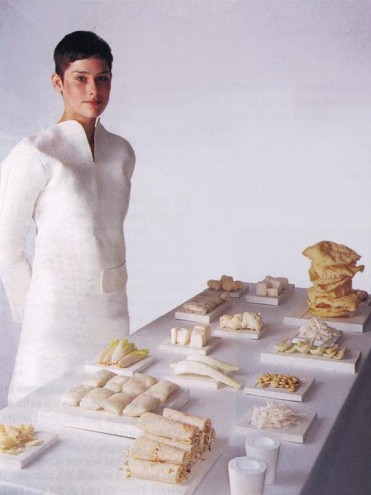

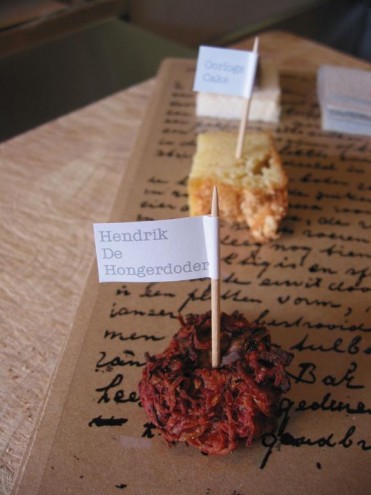

Salads made with ingredients that are all grown in the dark; meals made entirely from World War II ration ingredients; funeral dinners comprising only food coloured white; Christmas dinners where guests are each served a different dish, forcing them to share; rows of snacks with each set changing just one ingredient; peppers stuffed with emotionally rousing ingredients, such as pumpkin and ginger for memory; and 60-second meals, in which each dish took just 60 seconds to cook; are just some of Vogelzang’s innovations.

“Food is a very subjective matter that can be influenced in many ways. For instance, if you eat a five-star chef’s soup in a place that is cold, where people are shouting at you or where you feel uncomfortable because maybe you’re wearing the wrong clothes, you’ll never experience the true flavours of the soup. If you’re walking outside and it’s a beautiful day, butterflies are flying around and you’re in love, a fast food snack from the corner of the street can be really delicious,” she explains.

However, while intimate lighting, tablecloths hanging from ceilings, collective plates, edible cutlery and tables laid on the floor have all been used in various manifestations to embolden the emotions of the eating act, these never overshadow the sensory experience of the food. Vogelzang creates new flavour combinations based on such quirky selections as vegetables that grow in the dark, ingredients that start with the letter A or all-white food – throwing out the staid notions of basing menus on geography like Italian, French or Mexican. And it is always “honest, handcrafted and slow food”.

Nonetheless, despite enjoying playing with texture, flavour and aroma combinations, Vogelzang is not to be confused with being a cook. “I was educated to be an industrial designer and that’s really what I am – well, more of a product designer. I work with cooks as craftspeople. Cooks are the people who really know what happens when you put something in the oven and really know what to do with food. Just as if I had to be a chair designer and had designed a plastic chair, I would go to the craftsman who knows how to make moulds and use plastics,” she clarifies.

As Holland’s hot dinner party ticket, Vogelzang has worked with the likes of Li Edelkoort, Hella Jongerius, Ilse Crawford, Droog and Marcel Wanders, and her client list includes Hermès, Nike, Phillips and the Van Gogh Museum. Still, while she feels that being “experimental” is important, she resists being dismissed as “exclusive”. Her two Proef restaurants, in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, cater for a broader audience base and she likes to repeat her experiments to allow as many people as possible to experience them.

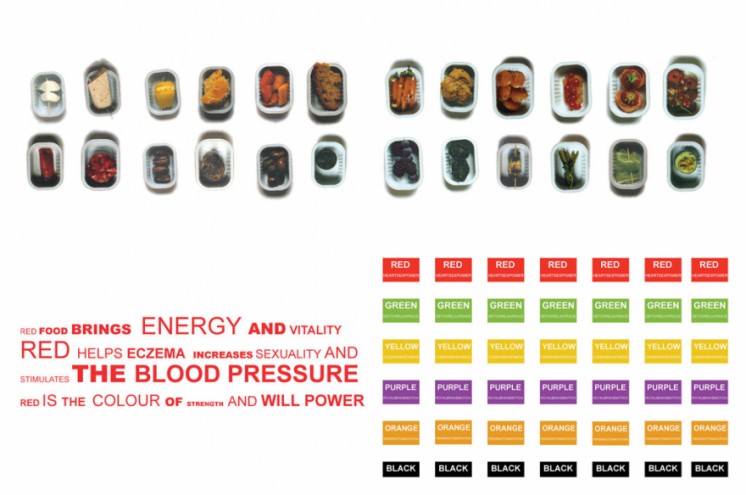

Significantly, she also likes her work to enter the problem areas of eating, such as obesity and nutrition. The restaurant and laboratory spaces regularly host day-care groups engaging children in fun activities around healthy food, such as making vegetable jewellery and pasta sculptures. On a larger scale, Vogelzang has also been engaged by various hospitals to reinvent food schemes. For one project at a paediatrics ward in the Bronx, New York, Vogelzang created a system whereby children identified qualities such as energy, sleepiness, friends and wealth with different coloured food, thereby removing the common binary of “good” and “bad” food.

Most recently, Vogelzang initiated the Dutch National Tap Water Tasting Day in response to the high level of water consumption in Holland. According to Vogelzang, the quality of the drinking water in Holland is very high, yet “we flush our toilets with it”. Having noticed that because of varying pH levels, water hardness, calcium, iron, etc, the water tastes different in every Dutch city, Vogelzang has collected water from the 12 main Dutch cities. During the event, people are encouraged to treat the water with the same respect that they would accord a wine.

“Food design is a new concept in society and designers are asking what to do with it. But I think there are many things for designers to think about. People say politicians should solve problems in society but I think designers should also be thinking about mass production, sustainability, hygiene levels, the empty fishing of the sea, world starvation, the over-production of food, children who don’t know where food comes from, people who want to eat meat but not see a dying cow, etc. So this is an open field for designers right now,” Vogelzang appeals.