Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city, is growing fast. For the largest city in Africa’s most densely populated country, space is valuable. The city may already seem bustling with its current 1.3 million residents, but with urban migration and natural population growth Kigali is expected to reach 3 million residents by 2025, and as many as 5 million by 2050. All this, plus the unique and demanding terrain on which Kigali sits, adds up to the need for a well-designed, compact, and sustainable plan for this fast-growing city.

Kigali’s city planners are keenly aware of the pressure they’re under. The idea for planning came in the early 2000s, when people began realising that informal housing settlements were popping up all over the city. This led to the creation of the Kigali Conceptual Master Plan in 2008, which focussed mainly on how to manage both population growth and density. With the memory of 1994’s conflict still fresh and the city left in near ruins afterwards, the need to build a city that allowed all its residents to live in harmony was the government’s main concern.

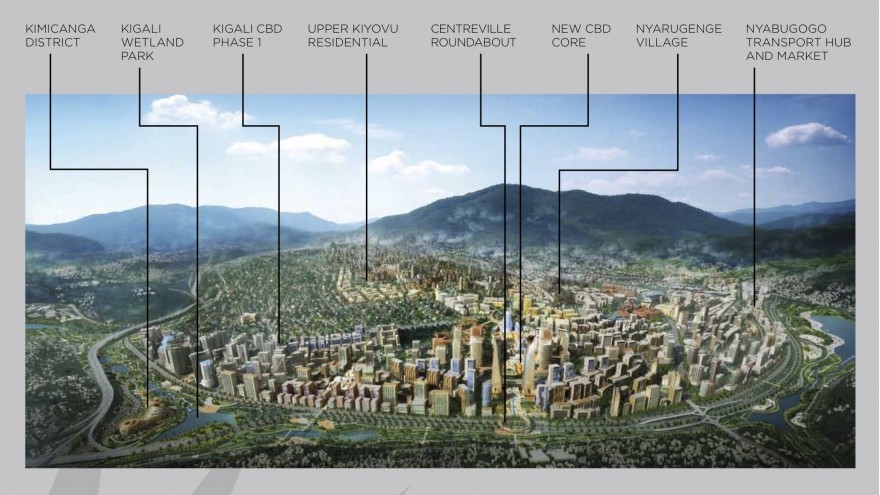

After 2008’s conceptual plan, more detailed planning was done for the central business district, Nyarugenge. Implementation, as well as plans for the city’s other two districts, began in 2010 and are currently in progress.

The aims of the master plan are broad and ambitious. The six goals for the development of the city are “character, vibrant economy and diversity”, green transport, affordable housing, “enchanting nature and biodiversity”, “endearing character and unique local identity”, and sustainable resource management. Nearly 40% of the city’s land is reserved for ‘nature areas’ –including a large central wetland area – and 19% is undevelopable due to steep slopes. That leaves only about one third of Kigali’s land for development of any kind.

To lead this daunting planning process, the government brought in Singaporean company Surbana International Consultants. Rwanda has earned the nickname the “Singapore of Africa” due to its clean streets and miraculous post-conflict economic turnaround, but now even its skyline is beginning to mimic that of the Southeast Asian powerhouse.

Indeed, one of the challenges the city planning office faces in implementing the master plan is a lack of ownership from the population.

People do not understand this as their project. They still believe this is for the City Council, laments Joshua Ashimwe, acting director of Urban Planning for Kigali City.

Outside the window of his brand-new ninth story office cranes swing by, erecting another of the many skyscrapers popping up downtown.

Another challenge lies in changing traditional living habits. With so little of the city’s land available for settlement, apartment living is inevitable and necessary. But apartments in Kigali are still a rarity, and are unpopular among Rwandans.

“We need to make people understand that living in an apartment is just as good as living in a house,” says Ashimwe.

Land is limited. Everyone still wants to build a luxury house.

"It’s quite a big challenge for us to ensure that we reserve our land for the future, while satisfying our interests now. We are trying to encourage densification, but people still don’t believe that they can live in a high rise.”

In the outlying areas of the city, Ashimwe and his colleagues are forever tackling urban sprawl, as they try to ensure access to water, electricity and roads.

Juggling the needs of a largely low-income and growing population, the economic demands of this developing economy and the strict environmental concerns in this hilly, high-altitude country seems an impossible task.

While the master plan has big goals for this burgeoning city, time will tell how it is implemented. Guillaume Sardin, architect and designer with George Pericles Think Tank, and former professor in Rwanda’s first architecture program, believes that the city’s future relies as much on individual actors than on the ominous plan itself: “It’s important because it is a clear plan for where they want they to go, but doesn’t indicate exactly how they will get there,” says Sardin. “It is now up to the architects in Rwanda to lead the way in terms of innovation and creativity in typologies, materials and cultural appropriateness.”