First Published in

Travelling through Bombay airport in mid-June 2010 I was not struck by the blast of heat and humidity that is natural pre-monsoon weather, but instead by the unnatural blast of badly dressed Indian people thronging the airport. It was a fest of the unkempt. The airport interior was a noxious mix of the gleaming Salvatore Ferragamo franchise adjacent to poorly welded public seating, plastic laminated announcement booths and the stench of toilets. All this was compounded by drab, shabbily dressed Indian people in thick denims and Versace style tee-shirts, girls with blonde highlights, professionals in ill-fitting synthetic suits, Blackberrys on belts and clunky, dusty black shoes.

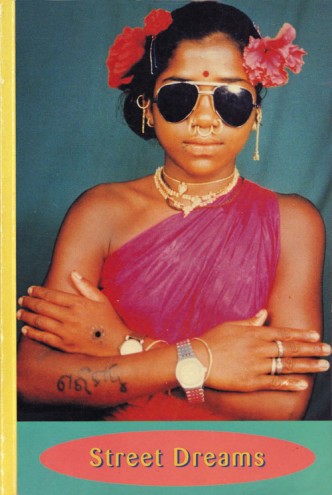

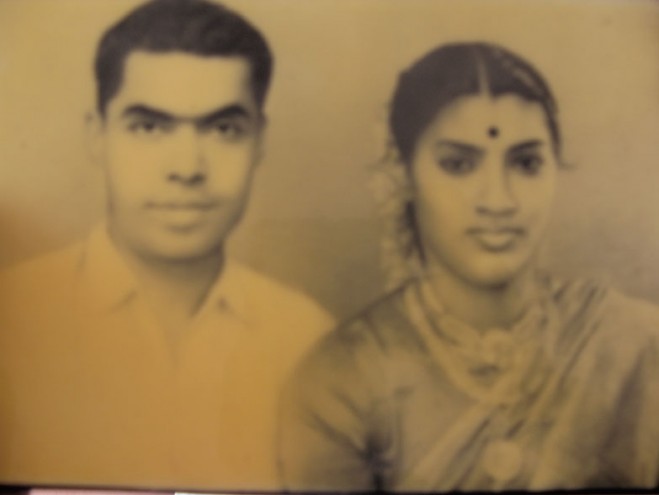

Once upon a time we were a good-looking nation. Not 300 years ago, but 30 years ago. Sometimes I imagine being an old woman, showing her grandchildren images of the India of her youth and saying, “Not long ago we were a sexy, stylish and original-looking country. We had elegance, grace, sensual rituals and rhythm to our daily lives. Our visual and material culture was plural and layered. We were irreverent about mixing styles, borrowed ideas and images shamelessly from everywhere but made them distinctly our own.”

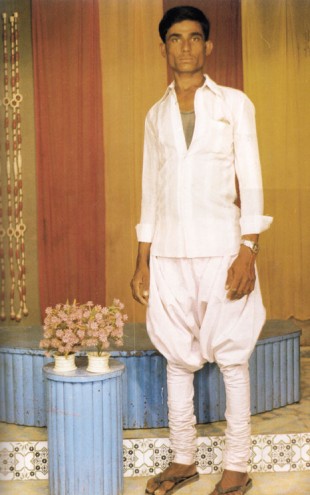

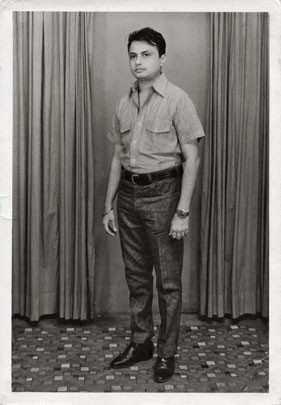

The last I remember, despite shabby and poor urban environments and dusty, barren landscapes, the majority of Indian people, irrespective of caste or economic status, shone like jewels, dressed in beautiful colours. My lasting impression of Bombay has always been of working men and women immaculately turned out in freshly ironed shirts and trousers, and of women wearing starched saris and flowers in their hair. Delhi, the city of babus (civil servants) and politicians had its own distinct style of safari suits and black leather clutch bags. Even the lazy babus were particular about their look, outwardly all efficient and ready for a day’s hard work. Men wore immaculately polished black shoes.

What happened to starched cotton shirts, glamorous chiffon saris and sensually plaited black hair with flowers?

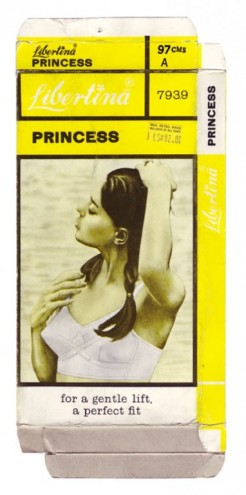

Summer was the time of finely woven cotton and voluminously airy clothes. Every season warranted shopping for fabrics and finely woven saris, imagining outfits and matching cholis (blouses worn under saris) to be made by tailors. And this was not limited to the wealthy. Even bras were made in cotton and came in beautiful graphic packets with charming slogans like, “for a gentle lift, a perfect fit.” All over India, people used to dress and groom accord-ing to region, season, time of day or occasion. Every region had a distinct visual style.

So, why are educated, upwardly mobile Indians now wearing skin-hugging jeans and closed shoes in the middle of summer?

The loss of material wisdom is not limited to clothing but extends to contemporary mass architecture and interiors. All over India, in the new homogenous architecture of high-rises are homes with stuffy sofas, faux collectable figurines, odd, cheaply embroidered cushions for an ethnic touch and fake wood flooring made of plastic laminate.

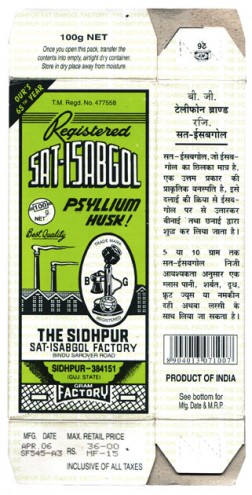

We are demolishing the cool havelis (beautifully carved, frescoed mansions with courtyards) of Ahmed-a-bad, the Art Deco houses in Bombay, the modernist 1960s style villas with shaded verandahs, wooden swings, mango trees and monkeys. We erase old parts of cities with six hundred year old temples, specialist incense shops, whole streets dedicated to bound paper notebooks or stainless steel utensils and hidden, open-fronted ayurvedic shops with elderly men sitting on cool ceramic tiled floors grinding pearls and gold leaf to make medicine.

We are destroying the India of sophisticated culture and deep know-ledge, the visual language rooted in sublime beauty that embraces imperfection and ugliness.

I refuse to attribute the deterioration and ugliness of our contemporary built environment to a “bad foreign influence” or to globalisation because that implies we are passive receivers or victims of outside forces, unable to discern between the good and bad.

On its surface, the look is simply the outward appearance and as such can be dismissed as superficial. But if one looks deeper, the look contains important signs of cultural and social values, of individual and collective creativity, of how things are made and their environmental impact.

I am not simply recalling a nostalgic image of bygone greatness. The way I see it, our past could provide a blueprint for the future of our material environment. It can show us how to support local businesses, promote a culture of repairing things and encourage resourcefulness and improvisation: eat seasonal foods, wear locally made fabrics and use terracotta vessels to cool water naturally. The past shows us that creating “The Look” can support micro enterprises that strengthen human relationships, foster individual creativity, empowerment and originality.

Can we leapfrog the stage of being mindless consumers? Can we as a nation be more intelligent than that? Can every creative person in India become a filter that knows what aspects of our material and visual culture have value and nurture these for a more humane, graceful and sensual future?

Nipa Doshi is a founder of the London-based design studio Doshi Levien. Her work is strongly influenced by Indian visual and material culture, which she combines with a Western sense of design and industrial production.

“Not long ago we were a sexy, stylish and original-looking country. We had elegance, grace, sensual rituals and rhythm to our daily lives. Our visual and material culture was plural and layered. We were irreverent about mixing styles, borrowed ideas and images shamelessly from everywhere but made them distinctly our own.”

Travelling through Bombay airport in mid-June 2010 I was not struck by the blast of heat and humidity that is natural pre-monsoon weather, but instead by the unnatural blast of badly dressed Indian people thronging the airport. It was a fest of the unkempt. The airport interior was a noxious mix of the gleaming Salvatore Ferragamo franchise adjacent to poorly welded public seating, plastic laminated announcement booths and the stench of toilets. All this was compounded by drab, shabbily dressed Indian people in thick denims and Versace style tee-shirts, girls with blonde highlights, professionals in ill-fitting synthetic suits, Blackberrys on belts and clunky, dusty black shoes.

Once upon a time we were a good-looking nation. Not 300 years ago, but 30 years ago. Sometimes I imagine being an old woman, showing her grandchildren images of the India of her youth and saying, “Not long ago we were a sexy, stylish and original-looking country. We had elegance, grace, sensual rituals and rhythm to our daily lives. Our visual and material culture was plural and layered. We were irreverent about mixing styles, borrowed ideas and images shamelessly from everywhere but made them distinctly our own.”

The last I remember, despite shabby and poor urban environments and dusty, barren landscapes, the majority of Indian people, irrespective of caste or economic status, shone like jewels, dressed in beautiful colours. My lasting impression of Bombay has always been of working men and women immaculately turned out in freshly ironed shirts and trousers, and of women wearing starched saris and flowers in their hair. Delhi, the city of babus (civil servants) and politicians had its own distinct style of safari suits and black leather clutch bags. Even the lazy babus were particular about their look, outwardly all efficient and ready for a day’s hard work. Men wore immaculately polished black shoes.

What happened to starched cotton shirts, glamorous chiffon saris and sensually plaited black hair with flowers?

Summer was the time of finely woven cotton and voluminously airy clothes. Every season warranted shopping for fabrics and finely woven saris, imagining outfits and matching cholis (blouses worn under saris) to be made by tailors. And this was not limited to the wealthy. Even bras were made in cotton and came in beautiful graphic packets with charming slogans like, “for a gentle lift, a perfect fit.” All over India, people used to dress and groom accord-ing to region, season, time of day or occasion. Every region had a distinct visual style.

So, why are educated, upwardly mobile Indians now wearing skin-hugging jeans and closed shoes in the middle of summer?

The loss of material wisdom is not limited to clothing but extends to contemporary mass architecture and interiors. All over India, in the new homogenous architecture of high-rises are homes with stuffy sofas, faux collectable figurines, odd, cheaply embroidered cushions for an ethnic touch and fake wood flooring made of plastic laminate.

We are demolishing the cool havelis (beautifully carved, frescoed mansions with courtyards) of Ahmed-a-bad, the Art Deco houses in Bombay, the modernist 1960s style villas with shaded verandahs, wooden swings, mango trees and monkeys. We erase old parts of cities with six hundred year old temples, specialist incense shops, whole streets dedicated to bound paper notebooks or stainless steel utensils and hidden, open-fronted ayurvedic shops with elderly men sitting on cool ceramic tiled floors grinding pearls and gold leaf to make medicine.

We are destroying the India of sophisticated culture and deep know-ledge, the visual language rooted in sublime beauty that embraces imperfection and ugliness.

I refuse to attribute the deterioration and ugliness of our contemporary built environment to a “bad foreign influence” or to globalisation because that implies we are passive receivers or victims of outside forces, unable to discern between the good and bad.

On its surface, the look is simply the outward appearance and as such can be dismissed as superficial. But if one looks deeper, the look contains important signs of cultural and social values, of individual and collective creativity, of how things are made and their environmental impact.

I am not simply recalling a nostalgic image of bygone greatness. The way I see it, our past could provide a blueprint for the future of our material environment. It can show us how to support local businesses, promote a culture of repairing things and encourage resourcefulness and improvisation: eat seasonal foods, wear locally made fabrics and use terracotta vessels to cool water naturally. The past shows us that creating “The Look” can support micro enterprises that strengthen human relationships, foster individual creativity, empowerment and originality.

Can we leapfrog the stage of being mindless consumers? Can we as a nation be more intelligent than that? Can every creative person in India become a filter that knows what aspects of our material and visual culture have value and nurture these for a more humane, graceful and sensual future?

Nipa Doshi is a founder of the London-based design studio Doshi Levien. Her work is strongly influenced by Indian visual and material culture, which she combines with a Western sense of design and industrial production.