First Published in

The Earth Literacy Project (ELP) was born out of my profound doubts about our current media environment. The nature of contemporary mass media is to report that which is extraordinary, divorcing news events from the context. The ELP aims to design platforms that help us grasp the realities of the global era that we live in more profoundly. As such, the Internet gives us the opportunity to experience the simple feelings and ordinary life of people across the globe.

Consider for instance the globalisation of food. In Japan our self-sufficiency in terms of food is quite low and we eat far more than we produce. "It goes without saying" that we are living in a world of global consumption - so when we fill a lunch box in Japan, most of the ingredients are imported from the United States, Brazil, South-East Asia and China. "It goes without saying" that they have travelled thousands of miles - a lot of energy has been consumed, and a lot of harmful gases have been released just to feed us. But as a nation, we generally aren't aware of it - it has "gone without saying".

Although we all know about globalisation and globalism, we don't realise how we are connected across the world and how these connections influence our environment. Instead, in this so-called global age, our sensibilities and imaginations are far from being global. Our economies are globalised, but our media environments do not reflect the realities of a global lifestyle. Even the Internet and satellite television haven't exercised their true potential as global media yet.

Globalism is not just about joining the international community; it is about recognising our planet as a whole - as "one globe". For this, we need more media that share our subtleties and contexts between us, globally. We need more platforms for recognising our global connections, for connecting all of these disparate pieces in more emotional and delicate ways, and for working with them as a connective and collective mind.

This is why I, through the ELP, wanted to design what I call "a global window" that suits these needs of our global age. By using the Internet to open a global window on the world, the ELP designs public sensory platforms that let users feel what is outside, real-time. We have called this "senseware" - a term used in Japan for designs meant to illicit specific sensitivities.

I first became convinced of this 12 years ago, when the Internet was just starting to get popular. I was the executive producer of the Japanese pavilion for the first Internet World Expo 1996. I organised a team of creatives and together we planned and produced the Sensorium - an attempt at curating a collection of sensibilities for the Internet age. Our work won the Golden Nica at 1997's Ar's Electronica, the world's premiere media arts festival. Breathing Earth, a program to visualise the Earth's seismic activities, was one of the works from that project.

During the development process, we focused on three big ideas, which have subsequently informed our work:

- First, that it is high time for the visualisation and monitoring of our living planet to be available to everyone on Earth.

- Second, that we should feel connected, as though we have "extended our central nervous system in a global embrace".

- And third, to recognise the whole as a bottom-up process. Just like a jigsaw puzzle, we can create a whole image of the living Earth through collecting and connecting small pieces of local data via the Internet.

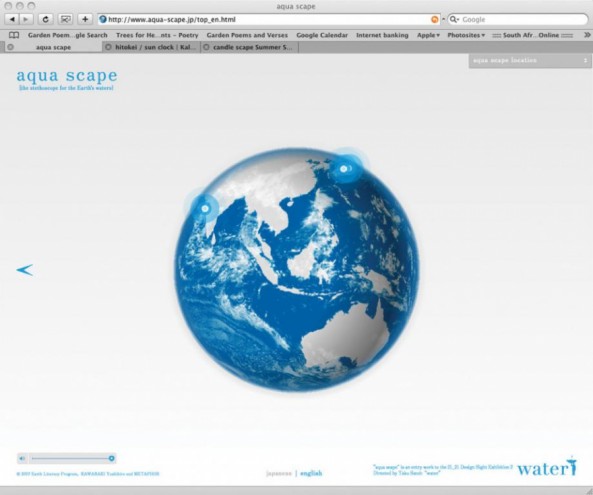

The first of the ideas was realised in Tangible Earth, which was created to encourage visualising the living Earth as one globe and to feel its dynamism in a more visceral way. We began work on this terrestrial globe using digital technologies in 2000 and introduced the first prototype in 2002. We've since exhibited upgraded versions, including the current version in 2005 at the World Expo in Aichi Japan. We are planning to present this work at the G8 summit this year.

The difference between this work and Google Earth, for example, is that ELP thinks it's important to combine digital technology and analogue tactility to create a more substantial and transformative relationship to knowledge. Current computers are still all about the keyboards and displays. They are extensions of a print- and visual-oriented technological civilisation - the very thing that McLuhan criticised as pre-historic electronic civilisation. We need to escape from these limitations, and seek ways to make our sensual experiences and intelligence comprehensive. I consider Tangible Globe as a first step in this direction.

The second of the ideas, connecting global citizens through the Internet as though it were a global nervous system, has been realised through the development of projects such as Hitokei (the Solar Clock) and Aquascape (the Global Stethoscope Project). Both of these projects aim to make our "online presence" and "context awareness" more vivid.

We often see the news of overseas wars and terrorist strikes, but we don't often feel these things are our own personal problems. If we were to hear the actual sounds of the sirens or individuals screaming in real-time through something like a global stethoscope on the Internet, it would completely change our emotional response to these tragedies. Existing applications in which one can hear cars going by, kids playing, and even water and birds, are already creating real-time aural connections across the world.

Rather than endlessly pursuing more advanced technology for entertainment, much more of such "senseware" needs to be designed to generate higher resolution imaginations. I want to create "infrastructure for our senses" - I believe this is the biggest contribution I can make to global society.

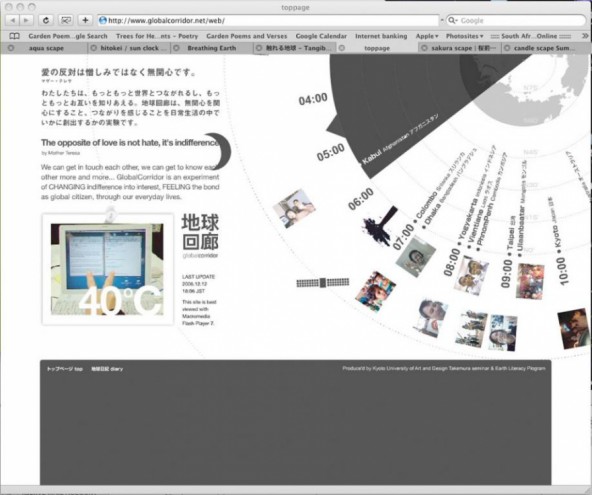

The Global Corridor project, which my colleagues and I planned and produced for the 2005 Aichi Expo, was our humble first step to realising this vision of "extending our central nervous system in a global embrace". We were motivated by 9/11 and its aftermath. The world was shocked by the terrorist acts and, even more, by the US's reaction.

If we had windows in cafés or public spaces in New York and other US cities, connected live to each corner of every town all over the world, Iraq and Afghanistan, and through these windows one could see environments where local children were playing around as a normal part of everyday life, I'm sure that we wouldn't rush into bombing them so rashly. If we lived in environments where we were in greater contact with how others live around the globe, day-in and day-out, then wouldn't it have been even harder for the politicians to manipulate public opinion and rush into war? Since 9/11, I have wanted to build a park in New York's Ground Zero, filled with "windows" connecting the world.

Maybe the key to a stable global peace lies not in politics or ideology, but in designing effective information environments. Along with eliminating terrorism or building economic parity, perhaps we should work on the "visibility gap" of our current media environments that don't communicate feelings of empathy for other people's existence.

The third theme, to recognise the whole through a bottom-up process, has led to a series of works that I have come to call Syn-active Maps. Although the amount of information and will that each of us have individually is limited and small, when combined like a jigsaw puzzle, it can create vast unexpected pictures with new collective merits nobody could foresee.

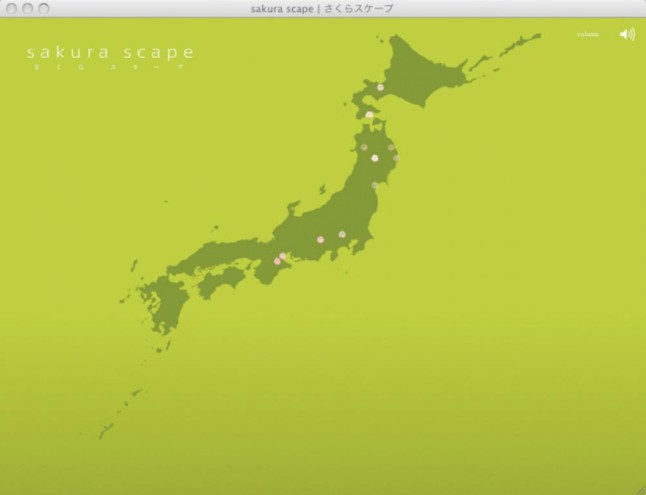

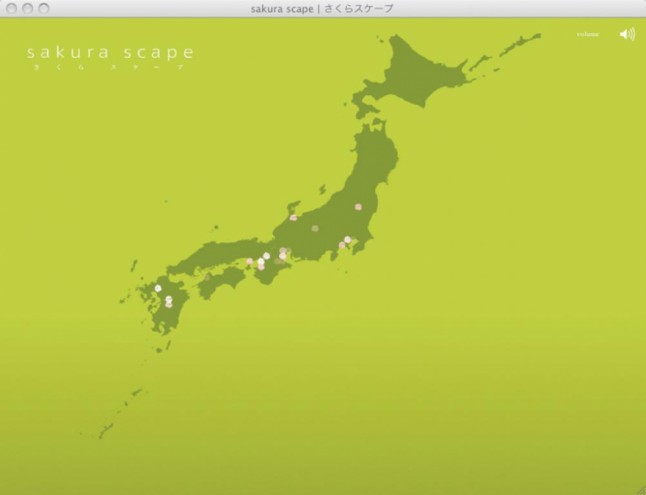

The simplest example of a Syn-active Map is Sakura Scape, which is a real-time map of where in Japan the cherry blossoms have begun blossoming and how the cold fronts have receded north. Another example is the Candle Scape, which is a real-time map we created for an event called A Million People's Candlelit Night.

In practice, the maps are an aggregate of images that people post from their cellphones. As the candles and blossoms appear in Sakura Scape and Candle Scape, each participant's "unheard voice" completes one piece of the jigsaw puzzle, second by second. You can observe the complete picture of how many people feel the same as you do, day-by-day in real-time. When I look at the message board map of Candle Scape participants for instance, I feel the existence of many people all over Japan who share the same feeling as I do in lighting candles. I feel their online presence, in a wave of empathy spreading offline too.

These days we hear more and more negative news about terrorism, war and environmental pollution when we look through the windows of TV and mass media. Increasingly, the world and my country seem to be hopeless disasters. But when I look at the Candle Scape and see the relay of unspoken voices from all over Japan and the world, it gives me the feeling that the world is not so hopeless after all. If we develop this kind of project throughout the world, maybe we can create a real feeling of "global connection," instead of this anonymous by-and-for-the-economy globalism.

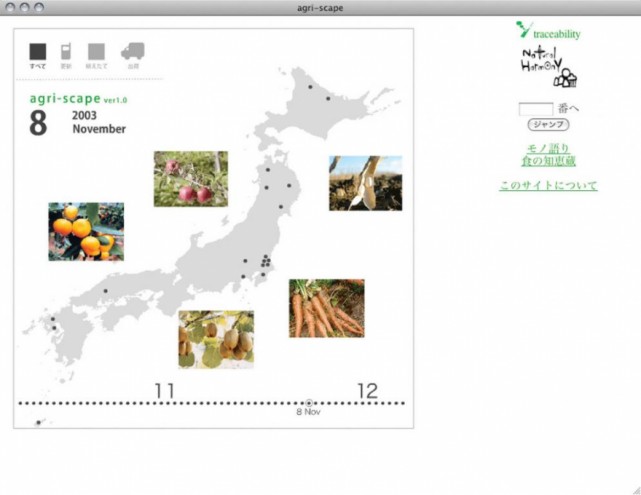

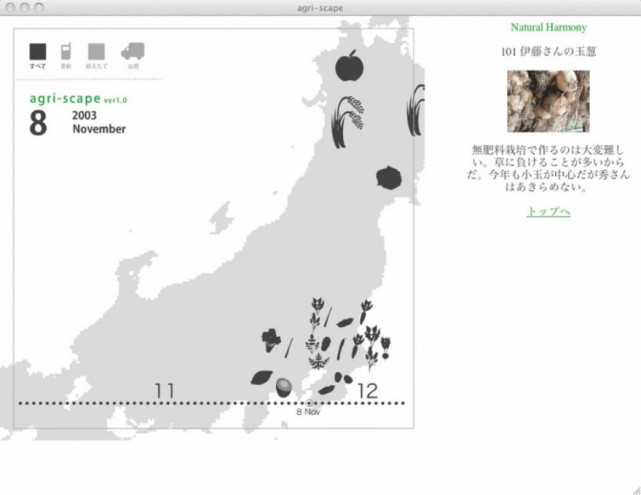

Another Synactive Map is Agri Scape, which is still an unreleased prototype. The map will offer visualisations of excellent farmers who are taking a major role in the future of Japanese agriculture. The shopper will access relevant information about the produce through their cellphones, tying the consumer more closely to the production and economic system that they are participating in.

This touches on something I mentioned earlier: Providing ways to bring, not just our television sets, but our lives and our imaginations into high-definition. By learning the background of daily products in high-definition, we provide our imaginations with broadband, enabling us to be more aware of how we are connected to the globe by our consumer and dietary choices.

I believe that one of our generation's most important tasks is to design information environments that throw light on the many black boxes in our society, teaching us to visualise the global economic structure that our life is based on. Designing information shouldn't just be about making it beautiful with graphics and packaging. Cool web design is not very meaningful if it never affects anything outside of the computer display.

There is so much more social and cultural potential for us to realise in information technology like the Internet. The world's focus so far has been on step-saving, cost-saving and time-saving pre-existing solutions, but we've not spent enough time focusing on new ways of imagining what we would like to use our technology for, and in what kind of society. Hardware and software are developing rapidly, but there's still a lot of room for developing social and sensory applications that will raise not just the bandwidth of our computers, but our personal bandwidth. A tightly woven society based on an open-source economy of ideas where credibility is mutually established is truly high-definition.

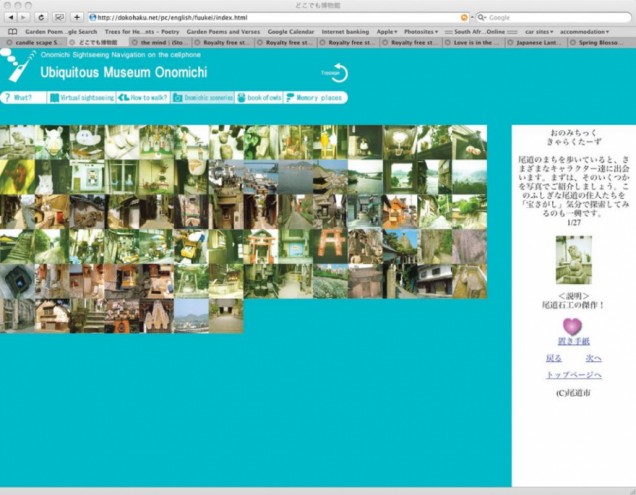

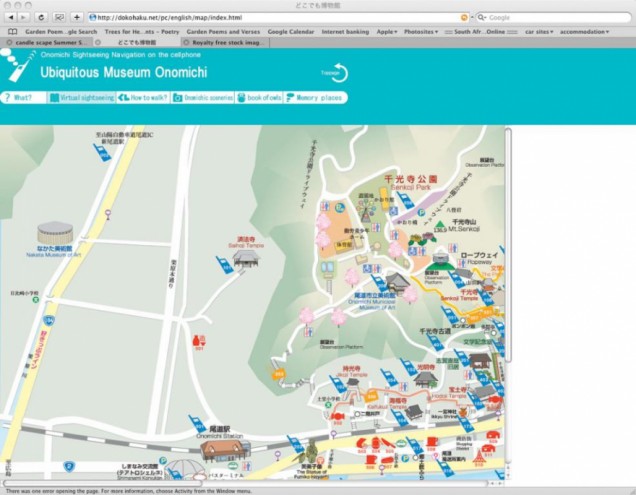

Finally, I would like to introduce the Ubiquitous Museum. Currently being tested in Tokyo, Onomichi and Kyoto, the project engages with the functionality of cellphones as mobile Internet terminals. People tend to think of information technologies as a substitute to physical experiences, but IT can just as easily enhance reality and enrich our physical experiences. The Ubiquitous Museum uses cellphone technology to add layers of memories and information onto the experience of being in a specific place.

Different to the Tangible Globe, which is a centripetal medium that concentrates information from the whole world into a 1-metre sphere, the Ubiquitous Museum is a centrifugal medium that distributes information, turning the entire planet into a living repository of embedded knowledge.

As such, the Ubiquitous Museum announces the first steps in an information revolution - something that only takes place every couple of centuries. Our current information environment, and therefore the manner of organising our human experience, was created in the Renaissance and the Age of Geographical exploration, during the 15th and 16th centuries. In those days the information revolution was typography and mapping, which offered new abstractions and panoramic representations of the world as information. But ubiquitous media will create a new modern style of experience, which will allow us to develop our cities as living texts, living museums.

In this new age, information will not only be processed by the static acts of looking and thinking, but through committing oneself physically through walking, empathising and leaving notes for others in the real world, encouraging a human capacity for more complex perception. Fundamentally, this information will not be provided, but rather be created through the relationship between the site and those who have experienced it. For instance, our car navigation systems effectively give us practical information - where to turn and such. Using the Ubiquitous Museum Project technology, however, we could also use the navigation system to get us creatively "lost". Streets we otherwise might have walked by without noticing, could suddenly turn into exciting mazes filled with high-resolution experiences. That's how ubiquitous information technologies should be used - as intermediaries to experience the places more slowly.

My conception of information technology design is to develop tools and systems that make people more sensitive, rather than create technologies that are so convenient as to eliminate the need for thinking, desensitising us towards other people and our environment. Technology exists to enable human potential; information technology to expand our creativity. Why build a society where things begin and end by simply pressing a button, where it doesn't matter if we think or not to make it work? That's an IT society geared to fooling us humans.

The machine-oriented civilisation that mocked humans, depicted by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, 100 years ago, has come to an end. In the maturation of our industrial societies we have developed machines and computers to handle our mundane repetitive tasks. We are becoming free to focus on doing that which only we, as humans, can do. This is the dawn of a "human-oriented" civilisation.

There was a time when the mass production of a standardised labour force was necessary for the mass production of standardised goods, and schools and militaries functioned like human factories. But now that a new civilisation, based on human creativity as its core resource can finally begin, the meaning and purpose of education, medicine and work can begin to change.

Of course there is much in our society today that we can't simply be optimistic about. We are plagued by environmental pollution, climate change, war and abuses of human rights, but at the same time, we are standing on the brink of enormous possibilities that can create a new civilisation. Easy pessimism is a sacrilege against the potential of human intelligence and creativity.

It's been five-million years since humans started to walk upright and 50 thousands of years since homo sapiens left Africa and spread across the world. Now, for the first time in our history, the time has come when we have a chance to re-evaluate our unique creativity and use it as a social resource in designing a more humane civilisation. I hope that the dawn of a new civilisation based on human creativity will one day come, again, from here in Africa.

Aquascape entails Internet-connected microphones at locations around the world transmitting the sounds of local water and rain to listeners all over the world, in real-time. For instance, one can listen to the sound of water dropping into a Suikinkutsu - a traditional Japanese garden ornament and musical device - in Shokoku-ji, a 700-year-old Buddhist temple in Kyoto.

The sounds are not pre-recorded, but the actual sound at that very moment, as if you were listening to a stethoscope placed on the other side of the globe and you could hear its heart. We have named it the Global Stethoscope Project. So far we've placed microphones in Kyoto, Tokyo and India, but we're hoping to place one in Cape Town soon. We are also planning to place one in Beijing during the summer Olympics, to make visceral the city's water shortages by listening to its dust storms.

It is precisely because we are living in a world deluged with visual information, that I wanted this work to focus on our faculty of hearing. I think that the opportunity to imagine what these places look like, based on these various local water sounds gives our imaginations a chance to expand.

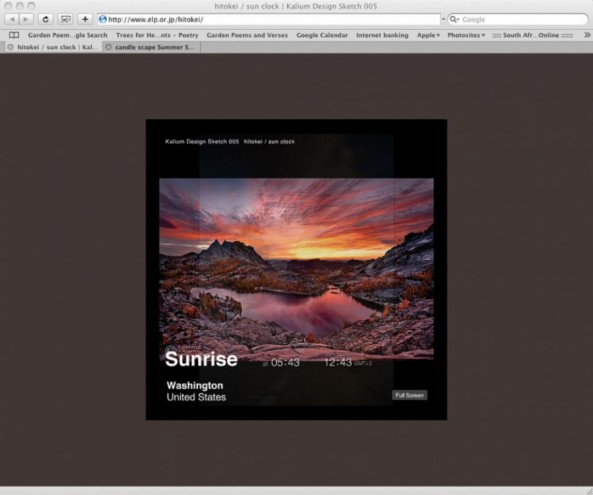

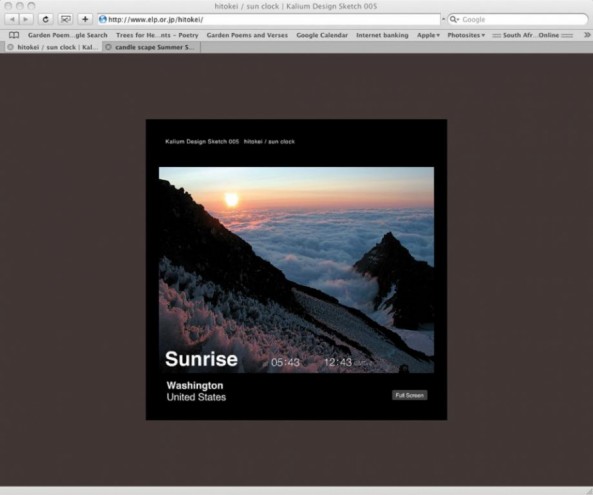

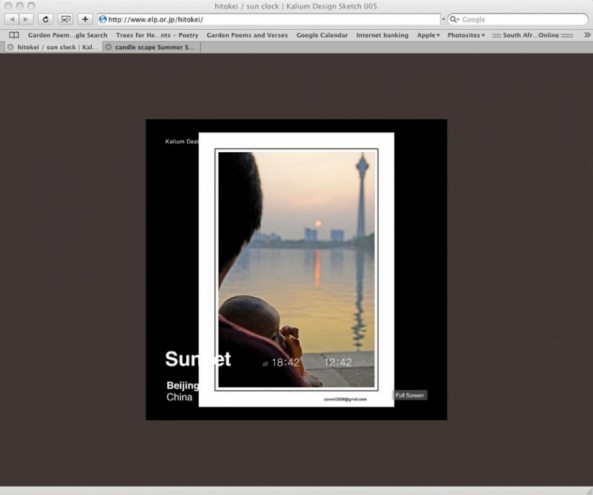

Hitokei - or Solar Clock - is a web "mash-up" program that calculates where the lines of sunrise and sunset are on the planet at any given moment. It uses this information to search, edit and present photos of sunrises or sunsets for these locations from Flickr. It was devised by Kensuke Arakawa, ELP's chief web designer.

Because Earth is constantly rotating, somewhere people are always greeting the sunrise and on the other side of the planet, others are enjoying the sunsets. Hitokei echoes Japanese poet Shuntaro Tanikawa's poem, Morning Relay, which describes how we are all connected to each other, invisibly, through this relay of sunrises and sunsets, from longitude to longitude.

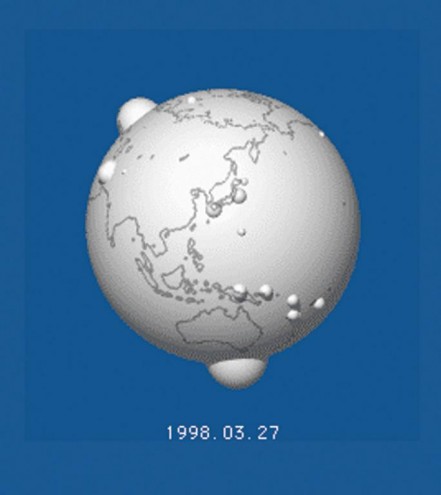

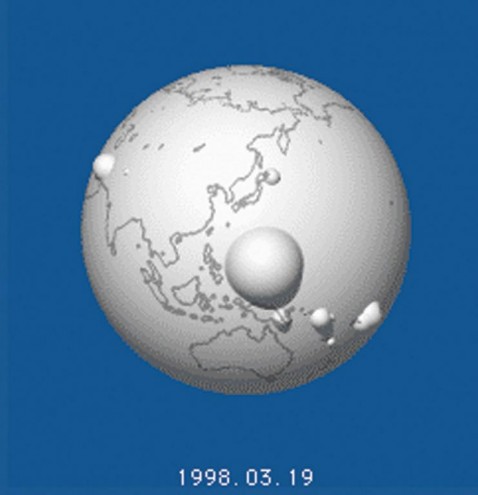

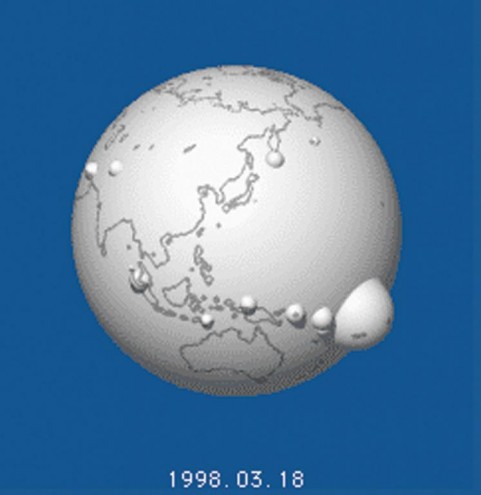

Breathing Earth is a program that monitors seismic activity around the world everyday and therein visualises the globe's aspirations and the stirrings.

In Japan, we experienced a big Earthquake in Kobe in 1995. What I recognised through that disaster was not the threat of earthquakes but the the lack of sensitivity and imagination to the dynamism of our living Earth. I was ashamed of the insensitiveness of people who live on the always breathing and fluctuating island of Japan. This is why I planned to create this window to visualise the "virtual" self-portrait of our living planet.

What's important here is not the computer-generated graphic output, but rather the fact that this is an actual portrait of Earth based on observational data from global seismic recorders that are frequently updated through the Internet. I was so excited when I first found the online seismic database that is incessantly updated in real-time. From this I planned the auto-compilation program that plotted the data on to the virtual globe on the web, creating a self-portrait of the Earth that would update automatically.

Tangible Earth is the world's first digital terrestrial globe. It is a 10-million-to-one scale of the actual planet - thus 1,28 m in diameter - and it displays data such as the position of the Earth to the sun; where the light and shade of the day and night are at any given time; cloud movements (updated every 30 minutes); the passage of bird migrations and air contaminants; and global warming, typhoon, tsunami and earthquake data.

The user spins it and handles it like any globe, but Tangible Earth interactively reflects and communicates the dynamic variables of our living Earth. By feeling and interacting with the Earth as one living orb, users get a concrete sense of globalism. As such, users are encouraged to imagine that things are interrelated across the globe.

The scale, 10-million-to-one of the planet's actual size, is an important part of the information design of this project. For example, the troposphere, the up to 10 000 m layer of air blanketing the Earth, where jets fly, becomes only 1 mm thick on this globe. Even a child can see how fragile the air layer covering the Earth is.

The Global Corridor came about because I didn't want to make the 2005 Aichi Expo, one that hadn't evolved from the 19th century; just people and objects from around the world gathered in a fairground of pavilions. Instead, the Global Corridor offered windows to all over the world, BY enabling participation in the expo via the Internet.

For the Global Corridor, we put the Tangible Globe in the centre of the venue and around it built several monitors called real-time globe windows. These windows connected to locations around the globe, each divided by one-hour time differences or 15 degrees of longitude, and enabled Internet video chats. We met children from countries that could not participate in the expo, such as Cambodia and Afghanistan, almost every day.

Of course some countries had less-organised network environments and were not able to connect as smoothly as others, but the principal of a school who participated from Afghanistan told me: "Japanese children always talked to the children in Afghanistan and that made us feel that we are not forgotten from the world, that we are party of the global society."

Cherry blossoms are a harbinger of Spring and when they blossom, it is Japanese tradition to get together and party under them, getting drunk, singing, or improvising haiku. The Sakura Scape is a website that people submit photos of cherry blossoms to via cellphones. These pictures are then automatically updated onto a map of Japan according to a zip code that is sent with the picture.

The point of this program is to archive people's cherry blossom experiences in real-time, while at the same time visualising the movement of the cherry blossom front as it moves up the Japanese archipelago. There is typically a three-month difference between the first cherry tree blossoms in south Okinawa and the last cherry tree blossoms in northern Hokkaido. By checking the site every day, users can follow posts from different locations in real-time, feeling engaged in the change of the season and the coming of the burst of energy that is the act of flowering.

This is not the meteorological agency's data or TV news, but a whole picture of Japan created bottom-up like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle contributed by individual real-time reports from various locations. It realises a sense of a big global cherry blossom out of the chaining of an enormous cherry blossom festival, made out of voluntary contributions of individual parts. When you look at it, you are transported to your own experiences of composing cherry blossom-inspired haiku at certain locations and these are connected with other people's experiences. Sakura Scape is driven by desires to participate and connect.

Candle Scape was created for A Million People's Candelight Night, which started in Japan in 2003. The event appeals to people to turn off their electricity for two hours on the day of the Summer and Winter solstice, and live by candles.

Some might use this time to spend with family, and others might take the opportunity to remember how beautiful the stars are that shine up in the sky. Maybe they've forgotten to look up for a while. Some might think about excessive energy consumption or environmental issues, while others might think about the world's unfairness and economic disparity. Turning off the lights opens up new windows on the world, letting us visualise new ways of living and new possibilities for a more diverse civilization.

Throughout the 20th-century, people strove to illuminate their cities, as a beacon of civilisation, but at this point we are over-dosing on artificial light. I think a lot of people feel the need to reset their ever-accelerating civilised lives anyway. The important thing is to connect these unspoken voices, and in this case it took the symbolic form of lighting candles.

The Candle Scape monitors the invisible connections, these ripple effects in real-time, through a mapping bulletin board. Participants of the candle night can post their messages from their cellphones or PCs, again with their zip code information, and a virtual candle lights up on the portal map, together with their message. As more people turn their lights off and Japan gets darker, this virtual Japan gets lighter and lighter with candle flames.

Although our individual wills or actions might be small, when we come together, like a jigsaw puzzle, we create a much bigger picture. Indeed, since our first year, the candle night project has spread unexpectedly in a ripple effect of word-of-mouth and emails. The Japanese Ministry of the Environment estimated that 5-million people participated in 2006 and 6.5-million participated last year.

This year, the G8 summit takes place on the day of the summer solstice, the same day as the candle night. We'll ask for messages to G8 representatives and on the future of the planet from locations and languages from all over the world.

One of Japanese society's prime tasks right now is to regain food self-sufficiency, which has dropped sharply over the past 40 years. This doesn't just mean percentage in volume, but rather revisiting questions of the quality of Japanese agriculture. We need to re-design the future of our food and farming, in philosophical and policy terms.

The ELP's Agri Scape project aims to help this effort by visualising an alternative future of Japanese agriculture from the bottom up, highlighting farmers who are excelling at agro-chemical, BSE and other food safety practices; establishing exemplary sustainable farming practices with minimal environmental impact; or contributing to a new kind of agriculture as total bio-regional design - integrating local endemic species and fostering both biological and cultural diversity.

With the Agri Scape map, these farmers are placed on a map of Japan, which is accessible on the Internet and through cellphones. When you click the icon for each farmer or their produce, a second frame illustrating their work pops up on your screen, designed to be easy to read on cellphone monitors.

Cellphones in Japan have optical recognition software linked to their cameras, so that they can read barcodes, for example. In this case, when you select agricultural produce in a shopping centre, these barcodes will enable you to download detailed information about the produce and farmers. The cellphone becomes a sort of magnifying glass: Whether in the shop or at home, you can instantly find out how an item was produced, both logistically and philosophically; find out when it was shipped; and hear about the people who grew it.

Using the cellphone as a magnifying glass allows the consumer to be more intimately connected with the producers, thus becoming more discerning about what kind of production system and philosophy their money is going to. By visualising production backgrounds this way, consumers are provided clearer choices and producers with higher standards are provided an opportunity to

be understood.

The Ubiquitous Museum project uses cellphone technology to add layers of memories and information onto the experience of being in a specific place. When you walk in the Hibiya district of Tokyo, for example, your cellphone could access information that the area was under water until the Edo period, some 400 years ago, and that its name, Hibiya, derives from the fact that there were shoals or shallow sea water, with lots of bamboo ("Hibi") used in seaweed cultivation.

The Ubiquitous Museum is a system for providing a variety of rich, experience-enhancing information to your cellphone. Its purpose is not only to provide historical and tourist information. Rather, by knowing that, for example, "this place was under the sea", we are encouraged to see our everyday world in slightly different ways and, for instance, wonder where the shoreline was when the city was created. As such, it provides a medium to make physical experience more profound, calling us to alter our appreciation of the world that surrounds us.

The Ubiquitous Museum project also suggests a new design paradigm of site- and context-oriented information systems. When you walk around town, or travel to unfamiliar places, it's more efficient for the place itself to tell you the necessary information on the move, rather than consulting guidebooks. In a society inundated with information, our basic information processing capabilities will be naturally expansive and based on the context of the site, unlike fixed tourist agendas or piecemeal search engines.

We're also working to build an interactive aspect to the system, so that people can leave notes here and there using cellphones. Cellphones with GPS information should be able to transmit emails with embedded location information, so that messages can be posted on virtual maps. Each visit will allow the user to discover the invisible post-its left by other people on these locations.

Such functionality makes it so that everywhere in a given town then becomes a repository of individual memories and accumulations of people's unspoken insights. Within this, each one of us becomes a sensor on the planet, exchanging our experiences on this living bulletin board called planet Earth. We can traverse our planet more enjoyably when people are the medium connecting and revising their personal topologies.