First Published in

I first came to Goa in the autumn of 1984.

It was the day that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated, felled by her own bodyguards in a volley of submachine gun fire, that I found myself on a train from Delhi to Bombay, heading to a place that in my consciousness constituted a far away paradise that I had only heard and read about.

I knew I was leaving the world behind, but I did not know to what extent. For those that have tuned in to Goa in the recent past, in the 1980s it was much more difficult to access than it is now. There were no direct flights from Delhi and if you were anywhere in dire financial straits like I was, you took a train to Bombay and then caught the overnight ferry. Goa was far, not just physically but also psychologically – it lurked on the periphery of mainstream Indian consciousness, due to its own peculiar history of Portuguese colonisation. It was almost another country.

So while the fires raged in Delhi in the macabre aftermath of the assassination, and the worst chapter in the history of Hindu-Sikh conflict was being written, I was safely ensconced in my 50 rupees a night shack on Baga beach, insulated from the rest of the world, in the company of like-minded, free-spirited travellers, sharing drinks, dreams and ideas about love, life and a better world. I saw no newspapers, nor looked at a television and as far as I was concerned, all was well with the world.

It was this disconnect that I think first attracted me to Goa: it was a world of its own, not concerned with what was going on elsewhere, an idyllic, self-contained tropical paradise in the midst of a frantic, aggressive, polluted and over-populated world. For a young man at odds with conventional thinking, Goa represented in those years, more than anything else, a freedom not found elsewhere. The sun, sand, pristine beaches, the tropical climate and easy-going lifestyle, the freely available drugs, a transient multi-cultural population of musicians, writers, poets, artists, drop-outs and free thinkers, the freedom to be whoever you wanted, to run naked into the ocean – it was heaven on Earth. It was like Tangier must have been to post-war European artists and intellectuals. A haven for all those on the fringes of “respectable” society.

So while neighbours cut each others throats in Delhi, and the forces of greed, divisiveness, racism and intolerance gained ground in the so-called civilized world, in Goa the ideology of love and peace, left over from the 1960s, still flourished and nurtured those that escaped to its shores. Travellers came from distant parts of the world for a couple of weeks and stayed for a couple of years, some even longer. Of course there was the lure of drugs, and there were the hard-core addicts, skulking around in the shadowy recesses of Anjuna beach, but mostly it was drug use for the sake of a liberated consciousness, a means of peaceful retreat from the painful realities of a world gone off the rails. In my first week, I met more interesting people in Goa and exchanged more inspired ideas than I had maybe in a year living in Delhi.

It was during that first trip that I decided that this was going to be home for me someday. Over the ensuing years, through many eventful trips, my relationship with Goa evolved and like most love affairs, with its own share of angst and joy.

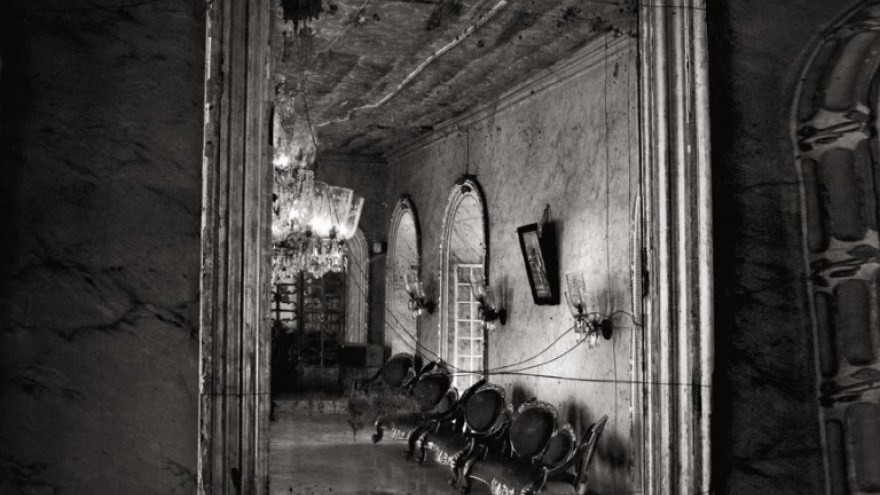

As the years passed and the world grew smaller with Internet, instant connectivity and the airline boom, Goa started to change slowly, one more innocent victim in the relentless onslaught of globalisation. Liberalisation opened up the Indian economy and a new middle class with an abundant surplus income suddenly came into being. Goa became the new destination for the Indian tourist, who had hitherto shied away on account of its non-accessibility, both physically and psychologically. Along with the new money came new consumerist aspirations. Fat cat developers from Delhi, Bombay and Bangalore, sensing the potential, started ravaging the landscape, buying and demolishing beautiful, old Portuguese villas and houses and erecting monstrous, concrete condominiums in their place. Vast tracts of gorgeous farm and orchard land became multi-star hotels. Land prices went through the roof and greed insidiously started replacing the gracious generosity of the simple Goan folk.

As the landscape changed, so did the unique energy that made Goa special. New money changed the equation completely. Farmers and simple village folk who had so far lived happy, peaceful lives were lured by the instant proximity of big city wealth. The divide grew between the rich and the poor and the crime rate escalated. Tourism grew too but now Goa was attracting another kind of tourist. They came in planeloads, on private charter flights and package deals from places like Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow. Gone was the evolved seeker/traveller, replaced almost overnight by the loud, brash pleasure seeker, seeking instant gratification at ecstasy fuelled rave parties. From love and peace to lust and greed in 10 easy years.

During these years my love for Goa ebbed and flowed. In 1996 I had bought a small house on a hillside in north Goa, overlooking a sweep of coconut plantations stretching all the way down to a sliver of brilliant sea on the horizon. For ten years I did not move there to live, choosing instead to visit frequently, sitting for hours on my verandah, rum and coke in hand, lamenting the decay of my much loved state, while marvelling at the spectacular landscape right in front of my eyes. There were moments when the sadness was too much to bear and I was ready to sell the house, make a packet, and move back to the madness of my urban life, giving up Goa as a dream that went sour.

In retrospect, I’m thankful that these were temporary lapses. In 2006, encouraged by the requirements of a long-term photographic project that I had embarked upon, and supported by the conviction of the woman I love, I moved bag and baggage and set up home on my hillside abode.

It’s been four years now and even though I still hit that occasional low, and a rush of nostalgia for the Goa that was, I consider myself blessed in being given the opportunity to live here. It’s still green and beautiful. I can still swim in the ocean. I still meet more interesting people here than I do anywhere else, my view all the way to the ocean is still uninterrupted, my dogs run free in the countryside and sometimes in the night while driving back home, through the narrow hilly country roads, passing silent villages and sleepy bars, I think about what an enchanted life I live.

Prabuddha Dasgupta is a photographer who hides out in Goa, shirking his worldly responsibilities, and working instead on his tan.