First Published in

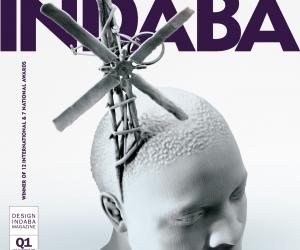

Some years ago while strolling through the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris in April, I discovered a unique nest in a tree, crafted by an avant-garde bird. Its outer layers were made from twigs, while the inner side was woven from plastic McDonald’s coffee sticks… A perfect blend of the old and the new, the organic and the technical, the natural and the manmade, bridging the past with the future!

This metaphor has inspired me ever since and has taught me to understand the future of arts and crafts, its possibilities and its requirements.

Ethnologic museums such as the striking National Ethnological Museum in Osaka or the endearing Indonesian National Museum in Jakarta, show us in often touching ways how mankind has crafted its way from prehistoric to post-modern times, creating culture and forging tradition. How in each instance, and on every island, the local population has realised hunting weapons and fishing tools, cooking vessels and utensils, patterned bark and dyed textiles, braided baskets and woven carpets for humble but perfectly designed abodes in local matter and ingenious indigenous techniques. Each tribe benefiting from other grasses and earths, other minerals and metals, other beliefs and ceremonies. Craft has been born from human life and needs, and therefore will likely sustain itself into the far future so long as our species survives.

These archaic examples of arts and crafts still inspire us today to re-design and re-craft. Through time, however, other techniques and materials have been introduced to enable the creative spirits to develop and broaden their horizons, borrowing ideas from other groups, regions and beliefs. Early on, craft started to travel, became a trading device, a business model, a cultural icon and a messenger. Cross-fertilisation started to influence local colour and regional pattern, and the trading path influenced its design.

The use of skin, feathers, beads and blankets can be traced back to tribes in the extreme north and the extreme south of our planet, from Africans to Native Americans, from Eskimos to shamans. The famous Silk Road opened Asia up to Middle Eastern splendour. While installing Buddhist rigour in Muslim expressions, Indian blockprints became the trademark of French provinces and exotic cashmere patterns became a staple of tradition, still today a landmark of European bourgeoisie. In telepathic empathy, several regions of the world developed similar techniques in textiles like dyeing indigo or weaving intricate ikat weaves – an early and spontaneous form of globalisation. Therefore, we can observe that craft has the power to express a local as well as a universal identity. This double-layered identity is typical of arts and crafts and indeed a guarantee of its survival.

Crafts developed through the ages, inventing new techniques at each step, tackling new matter – metal, glass and even plastics – and lending its endless variations to the expression of the individual artist within this common experience.

By and large, applied and artistic crafts developed and thrived in translating social, political and economic currents and illustrating the shifting world powers from Istanbul to Saint Petersburg, from Vienna to Paris, from Lisbon to Goa, from Udaipur to Isfahan, and from Kyoto to Como. The rigorous is alternated by the superfluous, the bold by the refined and the sombre by the splendid. Today’s world of antiques is witness to this everlasting change.

But man invented the wheel and started to rationalise the production of craft, still using his hands, but with a little help from the machine. The machine was in turn made high-performance and self-sufficient, so that our minds had to preview production beforehand, giving birth to the concept of design.

Design is a young discipline; a process engineered at the beginning of the industrial age that first and foremost developed function and then derived beauty from it. Up until today, function is the trademark of industrial and serial design, reluctantly giving in to the emotional and the ephemeral. But man started to tire of function alone and evolved to decor, surface effects and inlay techniques, blending industry, art and design – a movement that is making a revival at present. Then came a moment of great innovation, aerodynamic design and streamlined form. What followed was a time of space-age shapes and science-fiction volumes: our fascination with form for form’s sake was born. As time passed, shape changed shape, and decor followed decor as Wallpaper reintroduced wallpaper.

Function became remote, voice-controlled and morphed into virtuality, giving function an ungraspable quality. Thus arrived matter and the development of our fingertips as important consumer tools. Material development became a major focus of the art and design worlds, the concept of second skin was born, forecasting a future of genetic engineering and human cloning. The more virtual life became, the more tactile we wished to become. Matter called for colour to make up its mind and express its mood, ultimately making colour the overruling reason to select an outstanding work of design.

When design had acquired a sense of function, decor, shape, matter and colour, the insatiable and by now global market requested more. It needed a code, a name or a logo, or all of these, so it invented and perfected the brand: passport to international shopping pleasure. With this last step, the world could sit back, relax and contemplate a century of learning, amounting in a completed and perfected design process…

However, the demand for design had been explosive over the past decade, stretching our imaginations thin, and engendering an insatiable appetite for new experiences that created a world full of stuff; a globe drowning in design, a situation ready to explode. Today, we experience a need for reflection and we feel a need to rethink the (non)sense of design.

To answer the growing global resistance to constant renewal and limitless expansion, the years to come will call for humanity and integrity. It is time to empower goods with a new dimension – their own character; an invisible energy locked into the design process.

I believe that we will be able to make the object (concept or service) come alive to be our partner, pet or friend, and to relate to us on a direct and day-to-day level. Only when design is empowered with emotion will we be able to create a new generation of things that will promote and sell themselves; they will have acquired an aura able to seduce even the most hardened consumers on their own terms. Only then will design have acquired soul.

With a consumer ready to embrace the rare, the unravelled and the irregular in this quest for soul in a product, the arts and crafts movement is back at the forefront of fashion and interior styles. The ritualistic qualities inherent in the making of the craft object or the symbolic quality in the concept of a human service will gradually become more important. In a quest for experience, consumers will want to embrace their inner selves and choose merchandise to appease this need.

In an ever-more complex and information-riddled society, it will be important to touch base and to feel real matter, as if literally getting in touch with society. This is why the human-to-human revival of craft will flourish, lending well-being to uprooted Westerners longing to get in touch with their original selves. Well-being industries and eco-tourism will rely heavily on human skills for preparing oils, herbal medicines, massage and pampering, as well as food preparation. The immaterial approach to craft will request far-fetching conceptual design and strategy to ward off the ever more invading branded superpowers.

The question is, what does this all mean now for emerging economies and markets, and what influence will this longing for human design, local craft and the uniquely manmade have on local artistic developments and the globalcommercial markets? Before we can develop and sustain the craft movement in our world, we will have to design new strategies of retail and new categories of merchandise, new ways of sharing profits, and fresh ideas of showcasing and promoting these goods.

Based on 15 years of experience in a humanitarian trade adventure from Paris, called Heartwear – a collective of design friends developing crafts from different countries, such as pottery from Morocco, khadi from India and indigo from Africa – and armoured by past observations within the Design Academy Eindhoven’s Masters course for humanitarian design and sustainable style, I have developed the following observations:

- Crafts run on local time, a rhythm that is considerably slower than the hectic pace of international markets. This is why the public, especially Western audiences, easily embrace and discard items and trends, leaving entire regions without markets by the sheer strength of changing fashions. Therefore we have to develop strategies that play on a once-in-a-while rhythm, exposing and withholding these works of craft so as not to allow the public to get jaded.

- Based on better and equal opportunities, we will have to build up new networks of distribution; playing with exhibition-style events, elevated garage sales or highbrow home-selling parties developed to encounter clients directly, intimately and... sporadically. The retail space takes on the appearance of a gallery and its workings.

- Without doubt, we will have to settle for small quantities and higher pricing; after all, these goods are made by hand and created by man, one by one. Large companies should therefore refrain from delving into craft ideas, exposing them for one season only to discard them the next. Global markets ruin the sustainable perspective of local arts and crafts; they devour their ideas, modify their production rhythm, demand much in little time to only then demand little for a long period. The fatigued fashion cycles of style turn the wheel ever more quickly to ultimately feel unsatisfied about everything. Distribution will become the mechanism of editing the pace.

- Based on the power of slow change, we will have to stimulate the creation of better goods with higher creative content and a stronger emphasis on quality, discarding the nostalgic Western notion of the primitive and the exotic. Might some technology or some new material not exist in a certain region, I see no further reason to withhold the artists and artisans from its use. I believe that people’s creativity is apt to filter through new opportunities and options to create their own opinions and their own new dialect of design. Popular culture, outsider design and Sunday artists imbed contemporary images, technologies and sounds in their work, just like the Parisian bird making its wonderful nest. The embracing of the new will guarantee the survival of the origins of craft; a coming of age of craft.

- I believe that we will have to further teach art, craft and design in the emerging economies (as well as in our computer-driven art schools), through craft and design institutes, museum-quality craft centres and artist-in-residence initiatives in the “Third World”. Education certainly is a key.

- On the horizon, another social factor is emerging, creating new possibilities for the craft and cottage industries: the birth of the creative consumer. Educated by retail and press, informed by new media, trained by television and gifted with a broad schooling, we see the birth of a brand-new consumer group yearning to be involved in the creative process. Far-reaching studies are currently under way at economic and technical universities in conjunction with large companies such as Audi and Adidas, to figure out how the industrial process can be modified so as to let the consumer in as a partner. Obviously, here is a challenge for the arts and craft movement; one-on-one and one-of-a-kind, its structure is able to embrace the creative consumer at once – as it still exists today in societies from India and Africa, for example. Workshops in city centres could facilitate this encounter of talents.

- Arts and crafts can only develop in a new economic landscape built on the sustainability of style and in a networking economy. I believe that local markets are to be developed and will take on an important role. The people-to-people service industries emerging all over the world will furnish local, embellish local and serve local, thus enabling small cottage industries to emerge.

At the Design Academy Eindhoven I saw glimpses of this immaterial world to come, as translated by students from their IM Masters course. The mostly foreign students come to the Netherlands to train in the conceptual side of design, a discipline they haven’t yet mastered in their previous education. Their keen interest in the conceptual and the immaterial gives us food for thought and hope for a distinct and other future.

Working with the elderly was a goal of Thai student Ann Praoranuj. So she scouted a group of elderly persons from Eindhoven and art directed them into running a slow restaurant with slow service and slow food, completed by a slow chamber music ensemble for the opening of the event.

Banning the idea of personal rejection, the student Sang-Hoon Lee from Korea had a hair-loss problem in his youth that he wanted to eradicate. He proceeded to create a brand called “I’M-PERFECT”, collecting and editing the rejects of our industrial process. To general amazement, these rejects echoed the unique and lively quality of the handmade and the crafted. This concept made us understand much of our motivations to cherish, to hold and to buy. It also made me understand that the industrialised will ultimately be able to obtain a craft quality.

Today we see that borders blur between disciplines and therefore art is using fashion, fashion is using craft, craft is using industry, industry is transforming design, design is getting close to art... All of a sudden the traditional feud between industrial vs artisan and craft vs art gradually loses its interest. “Who cares?” is often the answer of a new generation of all-encompassing creators.

Therefore, I believe that we will see the day that the industrial will carry the soul of the crafted, while arts and crafts will certainly sustain through the discovery and acceptance, or even inclusion, of new and virtual technologies. There will come a day when the two fields will merge and become an indiscernible whole. This is when humans will have come of age, become wise and decided to opt for sustainable quality and style in design, intimately blending all which is believed to be contrasted today – young and old, old and new, healthy and naughty, nihilistic and decorative, male and female, First and Third World, ethno and techno... You may think I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one!