Sidewalk Salon:1001 Street Chairs of Cairo is an intimate portrait of the capital of Egypt seen from its sidewalk street chairs and the thousands of people who occupy them. These dilapidated chairs, which populate Cairo’s sidewalks, speak of the city from the level of its pavements. The street chairs are used in this book as tools to explore intimate details and the collective memories of the city. While documenting these original chairs, the book tells the story of the human dimensions of the city.

The project asks, how can we think about a city from the perspective of an object? How can an object shed light on the dynamics of a city and its web of social connections? These chairs bear the particular charm of imperfection. Their appeal lies in the way in which the passage of time, and the interventions of their owners to reverse it, has made each of them unique. Fixed and decorated with the resources at hand, they are old and worn out, yet startlingly fresh and appealing.

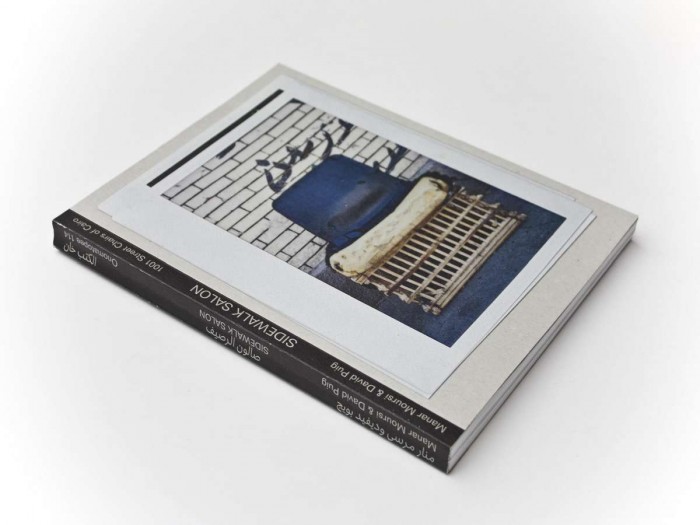

Each chair is shot from the front, with no human presence, close enough to see the detail. And each is mounted by the repetitive frame of a polaroid shot.

The project has multiple lives and outputs: installations, social channels, a website and the book. In 2011 it began as a Facebook page, where Moursi and Puig uploaded the images of the chairs from their archive. The website is a map-based site, which showcases six of the Cairo city walks undertaken by the two authors.

We talk to co-author Manar Moursi, a Cairo-based architect and designer and the founder of Studio Meem, an interdisciplinary design studio based in Cairo. Moursi’s work spans the fields of architecture, urbanism, design and art.

What inspired the Street Chairs project?

David Puig my co-author and I met in the winter of 2010 – exactly six years ago. From the moment we met, we connected immediately because we shared the same interests in understanding our city through walks, maps and literature. David was new to Cairo – I had been back for about a year since I completed my graduate studies at Princeton and was eagerly rediscovering it.

We decided to start going on regular walks together.

Our first walk was in Port Said Avenue which straddles Cairo from North to South. On this walk we noticed how the street chairs of the city formed an invisible thread along the sidewalk and we started to think about what seeing this very common object could tell us about Cairo.

We noticed the way people informally occupy the public space, creatively finding ways to both fix their chairs and create a space for them to be outdoors. We were curious about who the occupants of Cairo’s Sidewalk Salon were and how their ubiquitous presence affected the shape and the experience of the city.

These objects and their users therefore triggered a four year journey which culminated with the publication of our book Sidewalk Salon – 1001 Street Chairs of Cairo and map-based website.

Why always the empty chair? Did you ever think about including images of people sitting in them?

Our book and its images invites us to think about the possibility of making sense of a social reality taking as a point of departure an everyday life object.

How can we think about a city from the perspective of an object? What are the objects that allow us to unpack different layers of meanings in a set context? What objects are at the intersection of a web of social relations that can shed light on some of the dynamics of a city?

This is one of the reasons why we wanted to capture just the chairs in our images; as a way of emphasising their possibilities of telling stories.

How is the book organised?

Going through our archive of images, we began to notice families of chairs. The thematic series of the book are organised around these families, which reveal common formal elements in the structure of the chairs and shed a light on the multiple ways they are used on the sidewalk.

Some of those sequences put together particular types of seats widespread on the streets of Cairo, like armchairs and sofas, or curious pairs of twin chairs also found regularly on the pavement.

Other series focus on the lifecycle of chairs, showing different phases of their decay—from their amputations to their final collapse—or the miracle of their recovery with the help of various prostheses.

Diverse interventions to make street chairs more comfortable were also studied and classified by the kinds of material used: cartons, fabrics and cushions. Symbolic uses of chairs were also recorded; as signs of power and revolutionary struggle, chairs have appeared since 2011 in graffiti, stickers and advertisements plastered on the walls of the city.

So the other visual material included in our book are not found objects photographed by ourselves but found imagesfrom press agencies. Those images taken by AFP, Reuters or AP reporters have circulated in the media since the 2011 uprising and all show in different circumstances and moments the intersection of political events in Egypt and street chairs.

We have for example included a chair used as a weapon during the 18 days of the uprising of January 2011.

Will you tell us about the text, writings and poetry that went in the book with the images?

A varied set of texts—interviews, fiction, poetry and essays— intended to complement the catalogue of photographs we created in Sidewalk Salon, allow the reader a more nuanced view of the sidewalks of Cairo.

From fruit sellers to poets sitting in Tahrir Square, each of the persons interviewed revealed their own perspective of the city in flux.

For the security guard of the Russian Airlines office, the most moving memory from his archive of observations is a woman who feeds the street cats every day. Her care for other living creatures speaks to his feeling of connection to everything living, extending to the very dust of the city. For others, spending time with women on the sidewalk is a source of shame that must be concealed. For the younger crowd, women passing by are merely a source of entertainment, to be called at from their sidewalk stoops. For Mohamed in Dar El Salam, spending time on the sidewalk was how he got to first lay eyes on his wife.

The pieces of fiction and the poems inspired by street chairs, commissioned for this project, also seek to bring us closer to the occupants and owners of the street chairs. Writing about a passageway café in Downtown Cairo, Yasser Abd al-Latif recreates the atmosphere of one of the arteries of the city that brings the scale of the typical alleyways of Cairo to the wide avenues of Downtown. It speaks also of the forlornness of the nineties and the time spent on coffeehouses by wanna-be artists and creatives. Al-Taher Sharkawy’s “Elderly Company Preferred”, brings to life a bus stop seat located in front of the popular Horreya bar that any visitor or resident of Cairo has surely passed by but never taken notice of. Mohamed al-Fakharany reveals how informal vendors create makeshift seats with found objects in order to allow increased mobility and flexibility:

“Ward comes out every morning, carrying a chair and a set of scales... The chair: Not a chair as such. It's a piece of foam, square-shaped, that rests on a small crate. It doesn't always rest on the crate, however, so in a way one could say that the square-shaped piece of foam is the chair itself.”

Maged Zaher’s personal reflection on stillness and withering away while drinking tea on the sidewalk really offers a pulse of the times, and Amira Hanafy’s “Qamos El Thawra” inexorably ties chairs, couches and the culture of sitting outside to recent political developments.

In addition, our own essay, like the walls and the pavements that frame the images of chairs presented in Sidewalk Salon, can be read as the background against which to interpret the visual material of this book. It uses the prism of street chairs to reflect on Cairo and examine socio-economic, gender, design and political dynamics, and the relationship between these issues and the use of public space in the city.

How do you describe the character of Cairo?

Cairo is a city of paradoxes and dualities. It sometimes feels like the type of love that you know is unhealthy and you need to cut off but the moment you stop calling or distance yourself you feel a part of you was permanently carved out - you feel an irreversible ache and a never-ending nostalgia.

For me, it’s the street life, the sun, the biting humor, and the incredible diversity that the city offers in its built environment. The energy on the street sometimes feels like you’re walking out to a full city chanting om in one breath. There’s a reverberation that you feel on the surface that comes from the constant movement and occupation of street and sidewalk. Having said that, it’s a tough city even for the luckiest – repression and frustration are also embedded in its deepest pores and beneath its superficial substratum.

In a physical sense, Cairo is a city that also reveals itself as a patchwork of contrasting parts bound together: green islands, cliff-side settlements, cemeteries transformed into residential areas, old neighborhoods in medieval Islamic quarters, endless rows of raw red brick buildings developed along striped agricultural land, and gated communities with malls and wide highways sprouting out of the desert onto the outskirts.