When Michael Arad began sketching an idea for a memorial commemorating a day that forever changed the iconic skyline of New York City, he wasn’t doing it for a client, he was doing for it himself. Yet, 10 years later, it is the Israeli-American’s design that has come to life on the spot where the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre once stood.

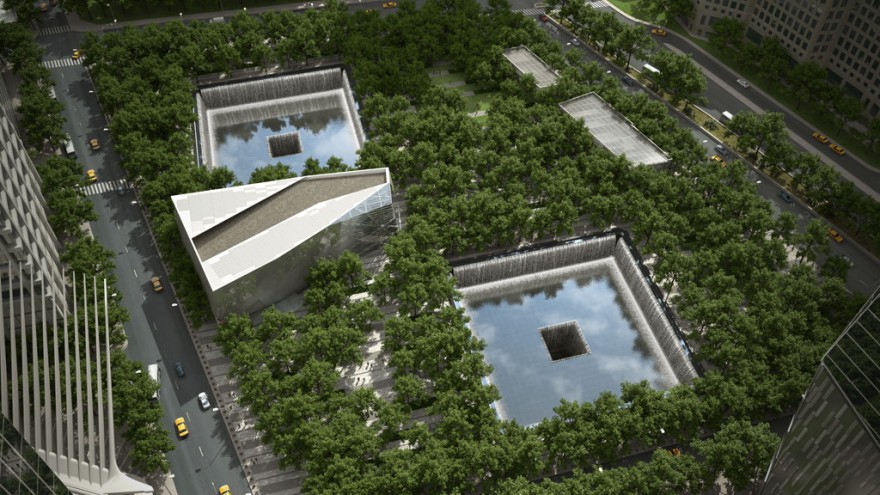

Opening on Sunday 11 September 2011, Arad’s Memorial Plaza consists of two reflective pools on the footprints of the fallen towers, the edges of which have the names of those killed on that day etched in bronze. Arad’s memorial is part of the re-development of the World Trade Centre complex, as envisioned by Daniel Libeskind, the master planner of Ground Zero. Pre-9/11, it consisted of seven buildings that were the financial hub of the United States. Now, construction continues to make sure that over the next few years, it will once more act as a nucleus of both economic and city life.

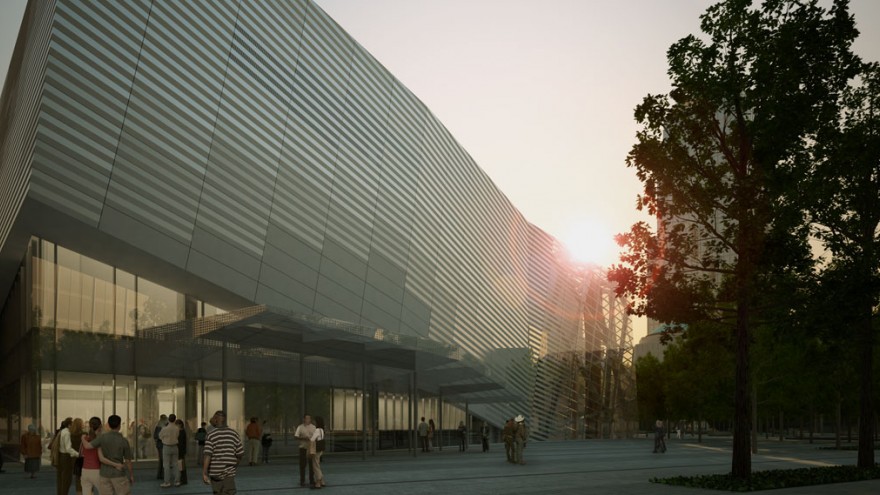

The Memorial Plaza, which Arad designed, is only one part of the 16-acre site, although it takes up half of that space. Dealing with the explanation part of 9/11, an accompanying museum opens next year and was designed by Norwegian architect Craig Dykers and his company Snøhetta, which also counts the Alexandria Library in Egypt as one of their previous successes.

Given the task of reflection, Arad trumped over 5 000 entrants in an international competition to create a design that would remember and honour the people killed in both the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 and the bombing of the WTC on 26 February 1993.

Like so many New Yorkers in the aftermath of 11 September, Arad was looking for a way to deal with what had happened. “I started drawing ideas a few months after the attacks. There was no competition at the time, it was just something that, as a New Yorker, I felt compelled to come to terms with,” Arad confesses.

He tells the story of living in the East Village at the time, and seeing a pastry store next-door putting up a cake in the window, with a picture of the Twin Towers on it, saying “We Will Never Forget”. “I was shocked to see that,” he says. “It seemed to me to be the last place I expected to see a memorial.”

But Arad grew to appreciate the gesture behind it, just as his ideas for what a possible memorial would be, grew too: “Those were the means at [the pastry store’s] disposal. If you’re a baker, you’ll make a cake, if you’re an artist or an architect you’ll start sketching or drawing.”

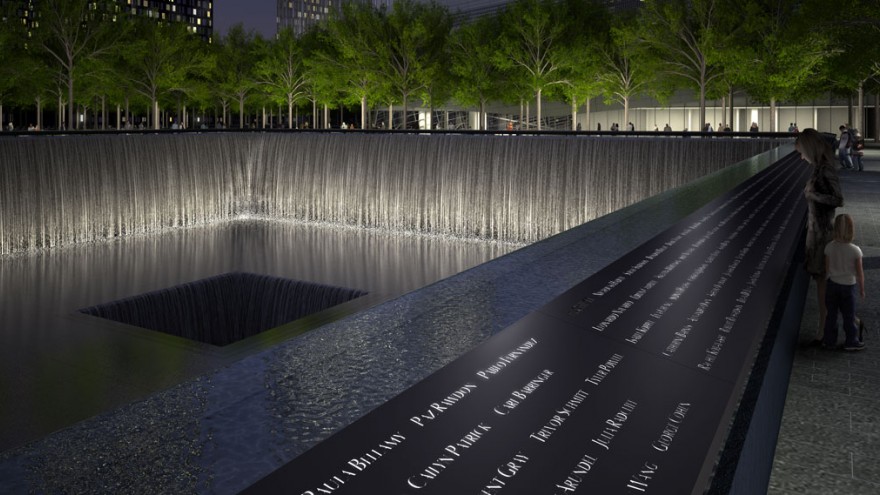

Arad had what he calls a “very inexplicable image” in his mind, of two voids on the Hudson River. “I imagined the surface of the river being torn open and these two square cavities with the water falling into them. ‘How could that happen?’ I thought. There was something inexplicable about it. But it was this idea of ‘persistent absence’ – that as water flowed into these voids it would never fill up, they remained empty.”

He spent close to a year working on this concept, and then built a little sculpture of a small fountain to capture the idea, put it on his rooftop and took a picture of it, with the Manhattan skyline in the background. “The absence of the towers in the sky were somehow being mirrored by these two voids in the river,” he describes.

That was the last he thought of it, and he put his idea away until a year later, when the competition to design the memorial for 9/11 was announced and he “began to imagine the kind of memorial that I would want to go visit one day.” For Arad, that meant an overhaul of what the World Trade Centre buildings had come to represent: “When I first started, this whole site was 30 feet below street level and there was a large building bridging over where the North Tower used to be. I remember it felt very cut off from the rest of Manhattan. I wanted this to be a living part of the city.”

He started by suggesting bringing the site up to the level of the surrounding streets and sidewalks, so that it would be part of the city. He also felt it would have an effect on activities in the area – for both loved ones paying their respects and New Yorkers going about their daily business. “These activities, happening side by side, enrich the experience of everyone. If this was to be a memorial site that was cut off from the life of the city, it would do a disservice to the people who would be visiting it. If it were to be cut off from the life city, it would atrophy,” asserts Arad.

“This way it’s part of our everyday life scar – not hiding, not showing off. It’s going to heal and become part of our city.”

The scar, so to speak, also displays the principals of sustainability. More than 400 trees are planted there, surrounding the memorial’s two massive reflecting pools. Swamp white oak trees create a rustling canopy of leaves over the plaza. It’s been created as one of the most sustainable green plazas ever constructed, with irrigation, storm water and pest management systems constructed to conserve energy, water and other resources. Rainwater will be collected in storage tanks below the plaza surface, and a majority of daily and monthly irrigation requirements will be met by the harvested water.

The memorial also displays the clear values of humanity driving the concept. “Values of individual loss and collective loss, of the lives of the people who perished here and the relationships they had to other people in the memorial,” Arad expands. He admits there were many heated conversations around a project so sensitive in nature, but that they were all held with mutual respect. One of the biggest challenges was how to arrange the names on the pools. The solution that came about was because of the activism of family members, who asked that certain relationships be reflected within the arrangements.

A total of 2 982 names are engraved in bronze on the pools. They include victims from the 1993 bombing and are arranged into nine broad groups, which reflect where people were that day: The four flights, the two towers, the 1993 attack, the Pentagon and the First Responders. Within those groups, names have been placed together by a process called “meaningful adjacency”.

“You may not know why certain names are put next to each other,” says Arad. “What initially looks quite random, not by age or alphabetically, is a whole process that came from us reaching out to the family members to find out what they wanted to see.” The arrangement of the names resulted from 1 200 requests that took a year and a complex set of algorithmic patterns to create. This is explained more fully in the Discovery Channel documentary Rising: Rebuilding Ground Zero, executive-produced by Steven Spielberg.

“There are ways to share the meaning embedded within the design, either by an audio guide or printed brochures,” says Arad. “When you are confronted with something as difficult as the fact that close to 3 000 people are dead, it’s hard to relate to. But if you learn about a single story, and then another, and then another, you begin to build up an understanding and communicate with a meaningful experience. That’s what we want to happen. And perhaps each time you come back you’ll hear a different story. There will never be a total and complete history of what happened that day. No-one fully knows that. It is unknowable.”