“Well trained in school, the architect of today must train themselves even more to become that urban entrepreneur and activist who can see opportunity where no one else does,” Alfredo Brillembourg weighs each word from the Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at Zurich University. He speaks slowly, with great enunciation, emphasising the levity of each syllable.

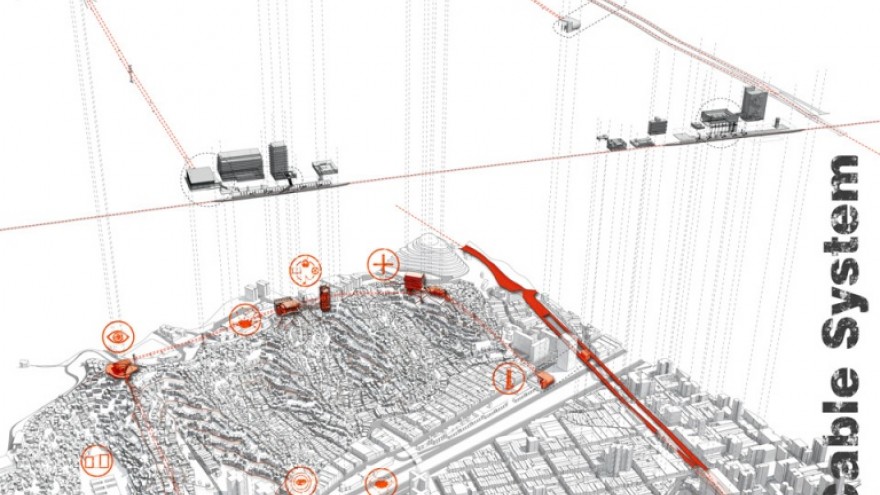

With 18 years experience as co-founder and –principal of Urban-Think Tank (U-TT), the company name should be clue enough: Brillembourg is a cerebral interviewee. But looking at the collective’s work in Caracas, Venezuela, he also walks the talk. The interdisciplinary firm emphasises researching and building for the informal city, and are most widely known for originally introducing the cable car as an alternate means of public transport in South American cities. This is not to mention their critically acclaimed Vertical Gym Prototype, which is licensed through Creative Commons, that is being implemented the world over.

“Urban-Think Tank sees the role of the architect today as a mediator between top-down and bottom-up governance and initiatives. The architect is well positioned as a multimedia thinker and great generalist able to become the producer of the city between these forces of top-down and bottom-up,” Brillembourg continues.

Due to speak at Design Indaba 2012, we ask him to introduce us to the thinking behind Urban-Think Tank.

What inspired you to start Urban-Think Tank?

Originally we started the venture as Caracas Think Tank in 1993. We were inspired by a feeling of conflict between the work we were doing during the day and the work we were doing on our own with our NGO at night. During the day we had an office, which was doing all sorts of commercial work like houses etc. At the same time, it was increasingly frustrating to work with the developers and the conventional standards of how architecture was practiced in Caracas. We also saw the political situation in chaos, and the urbanised hillsides of Caracas increasing at a dramatic rate with immigrants coming to the city and building their own urban zones.

So it was this conflict that inspired us, although we later realised that a city is made with conflict; a city is the conflict between the formal and the informal. We realised this during our walking tours, which we conducted at night and on weekends during the period between 1993 and 1998. We also had friends and other speakers from around the world giving talks in our garage start up. This evolved into us engaging with community leaders and, ultimately, them asking us to do projects.

At about that same time, Hubert Klumpner arrived in Caracas in 1997 and we began to think about establishing a company, which evolved into Urban-Think Tank. We kept Caracas Think Tank going as a research arm but used Urban-Think Tank as a project arm that could be contracted by mayors and so forth. We both abandoned our day jobs and dedicated ourselves wholly to Urban-Think Tank in 1998. Our first project was the Vertical Gymnasium.

What is the thinking behind Urban-Think Tank?

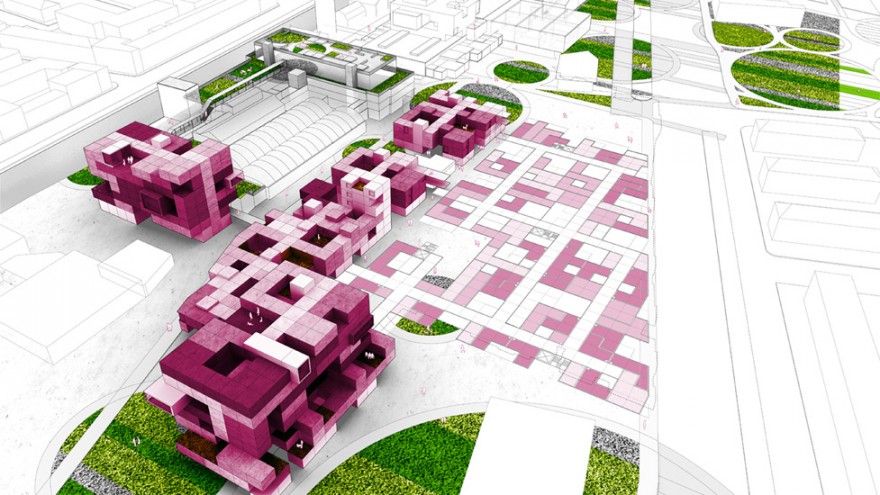

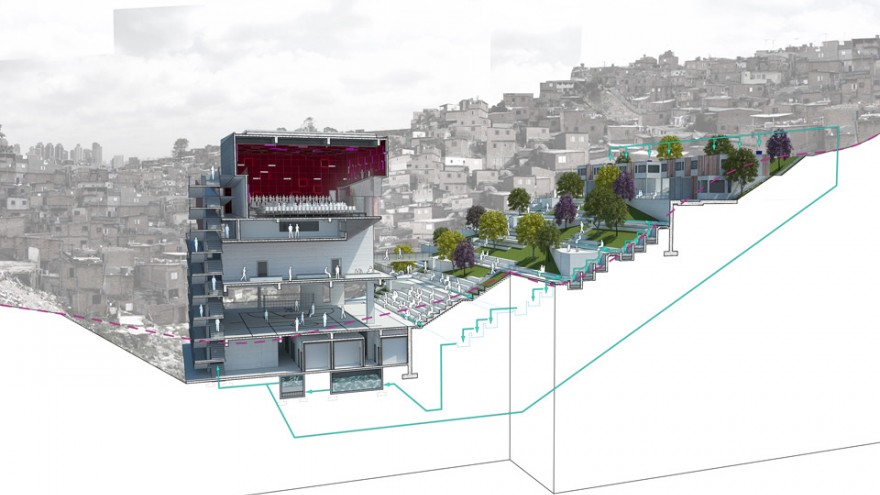

We started with analysing the transformational properties of the architecture object, such as the building, and the context in which it is inserted. In other words, we realised that once you placed a powerful building within the slum context, you created a kind of urban acupuncture, which actually resonates and creates a lot of change around it. So you see that change around the acupuncture of the Vertical Gym, Dry Toilet, or the stations and hubs of the metro cable car.

What we have realised is that these points are not like traditional urban points of centrality. Instead, these points want to be rhizomatic. It’s like an internet diagramme: The old diagramme is of a hub and spokes, like the wheel of a car. The new diagramme, which can be translated directly to a city, is a kind of matrix without a centre anymore, just points connected. So the real challenge is that, with this conflict between object and context, we can no longer think about urban design in a traditional formalistic sense of breaking blocks and orthogonal lines. We have to start thinking about a more connected matrix idea.

There’s also not enough money to tackle urban zones in their complete entirety, so we wanted to go against the idea of slum eradication because the slum has become too large. Therefor we had to find a new methodology for working in these areas.

What have the guiding principles behind your working methodology been?

We have actually started creating a toolbox of ideas, which you can find the beginnings of on our website. Some of them include prefabrication, going vertical, making networks, consolidating the public, analysing topography and having a retroactive manifesto.

How involved is the slum community in the whole process?

We have always worked closely with community leaders, who we have also learnt a lot from. With regards to one of our earlier projects, it was not our first choice to design and make the Dry Toilets. That was our clients – the community residents – who came up with the idea to put Dry Toilets on the highest areas of hillside communities where they had no white water and black water sewage. These were projects that came out of the common sense of the community.

How does Urban-Think Tank’s thinking manifest in its work?

Urban-Think Tank is building experiments. Our buildings have a few salient features. One, they are new prototypes. They are prototypes that come directly out of what we observe in cities and the cities in which we work in the Global South.

Two, we are trying to make new prototypes that can be multiplied. So the stations or hubs of the cable car can be networked and we can build hubs all over the cities, which has been so successful that many other cities outside of South America are also installing cable cars now. Then there’s also the Vertical Gymnasium, which is a densified sports field on several levels that fits exactly on the dimensions of a basketball court. The idea is to multiply these all over the world – 100 or 200 of them – so that we can bring down the price.

The idea behind these prototype buildings is that we can refine them over time. We can also make them open source so that other architects can build them and we can have a progression. This is a different approach to a lot of other similar work practiced by architects, designers and planners, who create solutions that function more like Band-Aids than replicable and systemic catalysts. We take our time, we seek funding for the research and we believe our solutions can be multiplied.

How do you feel about the words “slum” and “informal city”?

It’s important to consider from what perspective we are talking, because terminology is often shifting based on who is talking. As our friends in the Petare barrio in Caracas, the Perez family, clearly pointed out to us: “What you call a slum is our home.”

Urban-Think Tank has created a magazine called SLUM Lab, which aims at taking away the connotation of the slum as a bad thing. It is an acronym for “sustainable living urban model”. We want to turn around perceptions of the slum and bring the best possible buildings into the slum.

As you will see from our book, Informal City, we like the word “informal” because “inform” is not “out of form”. “Inform” is a hybrid that actually means something different, which can be interpreted, meaning that we can discover the actual form and logics of design that is in these areas.