David Goldblatt has been photographing South African structures for a very long time. For more than three decades he has traversed the country and captured buildings, monuments and public sculpture that express the values, power relationships and historical narrative of the country.

“In the 1980s and 90s I photographed structures that we, South Africans, had made during the era of 'baasskap' [domination], that time, from about 1960 until 1990, in which whites gradually came to exert dominion over all of South Africa and its people,” he explains. “It was the values we had expressed in those structures that I sought to elicit and explore in photographs and text.”

This culminated in his 1998 book South Africa: The Structure of Things Then that examines the country's cultural heritage as manifested in built forms.

From about 1999, five years after the first democratic election in South Africa – and continuing into the present – he once again took up his camera to document structures that have emerged post-Apartheid.

These are now on view in his new exhibition Structures of Dominion & Democracy, in which his focus is predominantly on the period after the fall of Apartheid.

I am probably too early. It will be very interesting for someone to do this in 30 or 50 years' time.

"At the moment there aren’t that many that have been built or planned," he says. "What we are seeing now though is quite a wide range of symbolic structures and I include sculptures, bronzes, mosaics and murals as well as a few buildings."

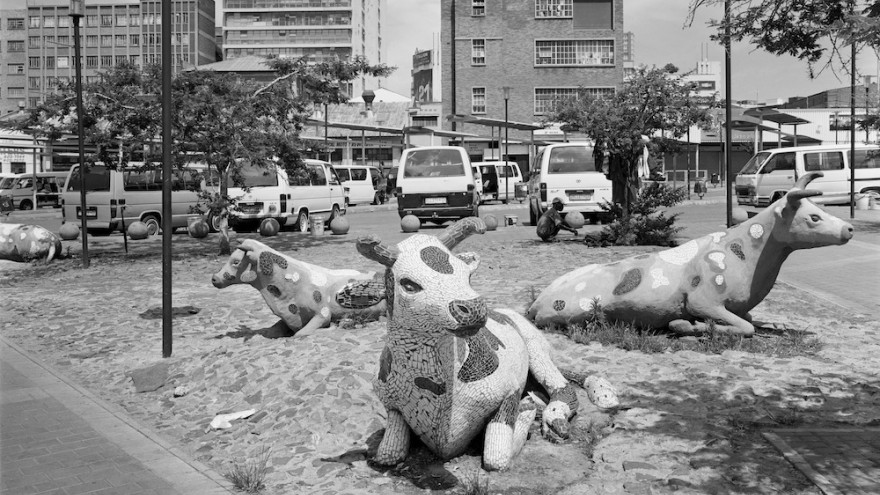

Goldblatt points out two post-Apartheid memorials that he considers successful because the communities have embraced them: a sculpture by Andile Maswangelwa of a herd of cattle, part of an installation by artist Andrew Lindsay in the middle of Transport Square in New Doornfontein, Johannesburg and a humble, local struggle monument in Steynsburg.

“If you go to Steynsburg in the Eastern Cape there is a little square there. In the centre of the square is quite an ugly little monument but it is a monument to the local people who died in the struggle. The pathways leading to the monument are kept very clean and are lined with beer bottles. It is clear that this is a very local, parochial phenomenon. The local community likes it and takes care of it. When my wife and I went there some months ago they had sown the square with blue daisies so it was very pretty,” he recalls.

One of the saddest memorials he visited has failed to capture the community's imagination, despite it's commemoration of an important moment in Apartheid struggle history: “In Cradock there were four young men that were assassinated by the security police in 1995 – they were known as the ‘Cradock Four’. I was present at the funeral where Allan Boesak and Beyers Naude were hoisted on men’s shoulders and carried in like heroes with the bishop of Port Elizabeth leading the procession. It was a very impressive ceremony and yet, the graves have been vandalised and the Cradock Four monument, a very big one on the hill above the graveyard, has not so much been vandalised as merely neglected.”

Goldblatt believes that these structures are collectively "expressive of values in the new, still nascent way of being in our society".

Structures of Dominion & Democracy is on at the Goodman Gallery Cape Town until 6 December.