First Published in

"I'm not naturally a very ornamental person," says Jasper Morrison who, early in his career, designed objects like a hat stand from an office chair and an airconditioning duct; and a table from a circle of glass supported by flowerpots.

His first industrial commission was door handles for the German manufacturer FCB. He was attracted by an image of an early coach handle, taking direct inspiration from its shape and turning it into a modern door handle. The door knob that went with it was based on a light bulb.

"A lot of inspiration can be found in very mundane places and mundane objects," explains Morrison. "I did not want to be a creator in the sense of trying to create shapes. I prefer the attitude that, as designers, we are reprocessors." Other clients followed – the Italian furniture manufacturer Cappellini, the Swiss furniture company Vitra. In 1988, Morrison designed a room set for the Berlin Design Werkstadt exhibition. It consisted of chairs, tables, a chaise longue, four walls and a door – all made from plywood.

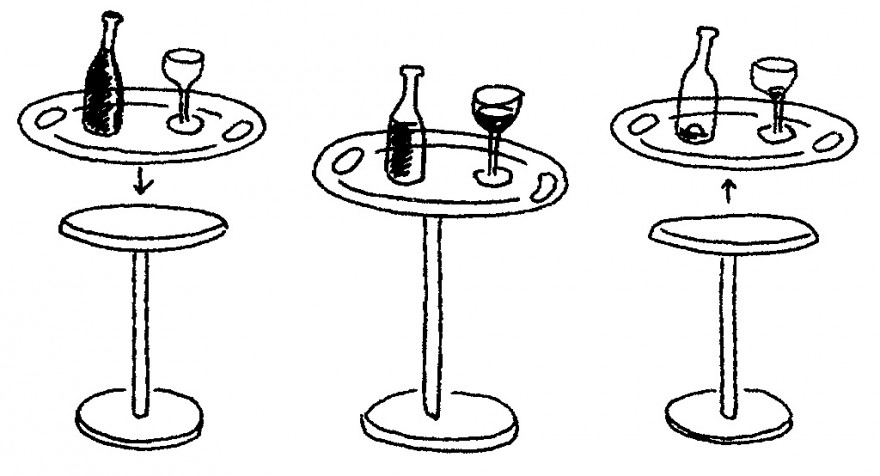

The simple lines and forms emphasised how Morrison redefines familiar household goods and uses new materials and technologies to enhance their appearance and functionality.

Morrison continued to receive commissions from more clients such as Alessi (steel kitchen tins), Flos and Magis, and Rosenthal (tableware). There was even a Hanover tram system that took three years of intensive work. "We designed it in a way we would like if we were passengers … as designers we should not forget that we ourselves are consumers and should be using the objects we design."

In the early 2000s Morrison set up a new studio in Paris and now divides his working life between Paris and London.

Morrison's enduring "homage to the beauty of everyday things" is increasingly displayed in his "super-normal" products, which he describes as "the kind of design that may not surprise anybody but would be readily enjoyable to live with".

"It seemed to me," he told DI delegates, "looking around my house, that my favourite objects were not so much the sensational ones, but the more discreet ones, and in some cases I had been using them for many years before realising how fantastic they were.

"I started to realise it's an incredibly sophisticated world. Many objects look like they look, because they have been refined over many years. Normal objects become super-normal through use, you can't really design them."

He added after the presentation: "I'm really interested in why a lot of design seems to be a form of visual pollution. There's a way to a more sophisticated kind of design if we resist the urge to express our creative genius so much. Design is too visual and there's not enough emphasis on the content. Normal things are often more effective than designed things – functionally and atmospherically.

"Where there's genuine quality there's no problem (with more). For example, in the case of Jaime Hayon, I think his work is so genuine and so good that's fine. It's more the collective effect at a less accomplished level that's causing the trouble."

Morrison found the Design Indaba a source of personal inspiration: "I always wanted to meet Neville Brody and I met him on the way to Heathrow, and then I met Jaime Hayon on the plane. There were many great speeches – Jurgen Bey, Hella Jongerius, the Vignellis, Jaime... It was very well organised and a great occasion."