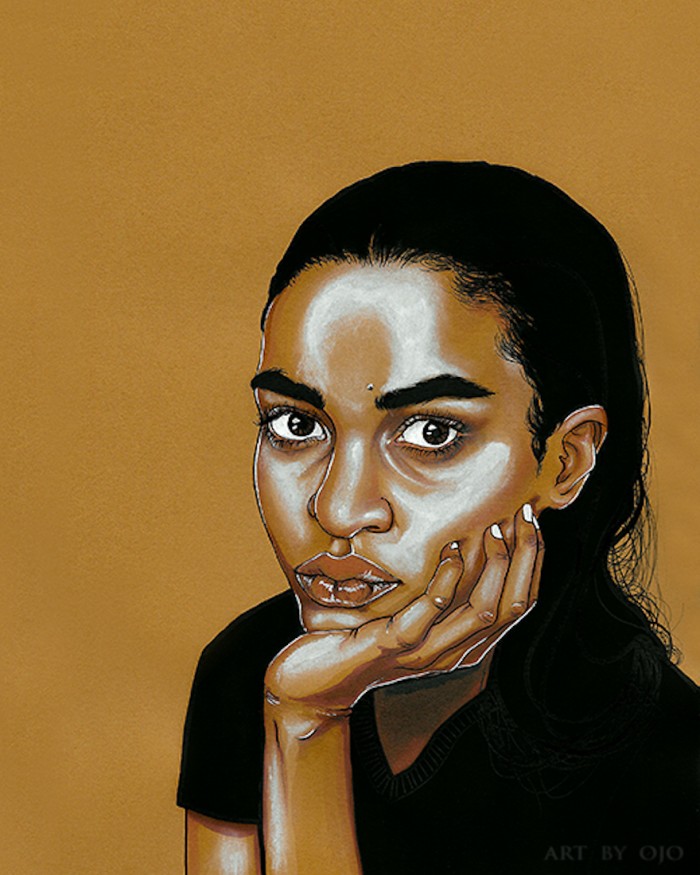

Ojo Agi uses her platform to challenge the lens with which women of colour are often portrayed. A Nigerian who was born and raised in Canada, Agi also explores her identity as a creative in the diaspora and through her work she is able to respond to the pressures placed on African creatives who feel pigeonholed by Western ideals of African art. We spoke to Agi about her latest series, Daughters of Diaspora.

How would you describe your work?

This is probably the toughest question, as I don't think too much about my work in words. I'm usually trying to capture a feeling, an emotion, an expression. So I guess I could describe my work as expressive portraits. But the expressions are always very subtle and, sometimes, ambiguous. To me, it speaks to the complexity and layers of the women I'm trying to depict. My work allows people to project their beliefs and personalities onto it since the portraits appear to be quite neutral. I think what is seen depends largely on who is looking.

How would you describe yourself as a creative?

Creatively, I like to try new things. I'm still developing my style and learning how to translate it across various mediums. So I'm very open to trying new paints and techniques. I also have a very collaborative spirit, so I like to work with other creative people. I don't believe in copying somebody's style. If you like what they do, it makes more sense to work with them than to try to adopt their aesthetic. I wish more people realised that.

What are the themes that inform your work?

My work focuses on representing black women in ways that challenge the dominant stereotypes and narratives, which I've always felt confined by. The themes I tackle most are race, gender and cultural identity.

What was the inspiration behind Daughters of the Diaspora?

The series was inspired by my upbringing in Canada, where black people are a minority and those from Africa are even less represented. I thought a lot about race and cultural identity growing up, specifically how this impacted me as a woman.

I never saw positive reflections of Africans in the media and it was difficult to find pride in that part of my identity.

When people set out to compliment me, they did so by telling me I didn't "look African", as if all Africans look the same and this look is undesirable. If I wasn't informed about a particular meal or genre of music specific to American or Caribbean culture, I was told I wasn't black enough, as if my racial identity automatically dictates my cultural identity. So the collection sets out to represent young, black African women as I see them, but also challenge stereotypes about what it means to "look" African or "be" black. I also wanted to celebrate our names, a main indicator of our heritage--so each "daughter" is given a cultural name such as Gugulethu (Zulu for "our treasure/pride") or Somtochukwu (Igbo for "join me to praise God").

In a recent blog post, you unpack the politics of authenticity in African Art. Were there any moments in your career that you felt boxed in by what is considered “authentic”?

It's really difficult to know why you didn't get into a particular show and I can never say this with certainty, but sometimes I do have suspicions that there's an expectation of what kind of aesthetic my work should have as a black/African artist. I'm still very new to the art scene so I'll have to keep my eye out to make sure my work is being fairly judged on its merit and not on a performance of my identity.

In the article, I argue that the expectation of authenticity placed on African artists is used as a tool of exclusion. Firstly, authenticity has not been defined by us but, rather, stereotypes and expectations born out of colonialism. Second, if we don't live up to these expectations, we risk being excluded from Western art institutions. And lastly, it seems that only marginalised artists have to live up to the label of "authenticity". It is as if our identities are something we have to explain or prove.

So it's my hope that we start to see the artwork for its merit and let each artist tell their own story, instead of grouping artists together based on their shared race or nationality and projecting biases onto their work.

How has experiencing both Africa and the West impacted you as an artist?

It's interesting that you ask me that because I was just reflecting on my experience in Johannesburg, South Africa this past November. The galleries I visited were full of black/African artists, which I've never seen in Canada outside of Black History Month. I think often black artists here are tokenized and asked only to participate in "black" events, but not invited to showcase their work other times of the year or for the general public. There are definitely spaces, curators and organisers working to combat this, but the exclusion from major art institutions is noticeable. I also found a much greater interest and urgency for my work in the short time I was in South Africa than I find here in Canada, which was validating and much needed! I hope to get to visit again.

What will you be working on next? Do you have any future projects in mind?

I'm looking forward to expanding "Daughters of Diaspora" using people I meet in real life to diversify the type of beauty shown and capture the stories of other women. I think the first set of illustrations was really great for speaking my truth, but going forward I'd like to include as many women as possible, particularly queer and trans women who can speak to a different perspective than my own. I'm also considering other projects that will allow me to explore new mediums, such as textiles and embroidery.