First Published in

Architecture is a form of art that demands the interweaving of the visual, conceptual, sensorial, accidental and social, looking to establish small parcels of order in a context infinitely disorganised,” believes Argentinian architect Jorge Mario Jáuregui, who has lived and worked in Rio de Janeiro for over 30 years.

In 1994 Jáuregui won an open competition to lead the largest informal settlement upgrade ever in Latin America. Called Favela-Bairro, he advocated that the nine-year programme build physical, social and economic infrastructure by working within the logic of the existing organisational and support structures. Besides supplying essential infrastructure such as water, drainage and electricity, and building new roads for refuse collection and emergency services, social infrastructure such as schools, sports centres and community facilities was also prioritised. Jáuregui’s work on the Favela-Bairro programme was recognised by Harvard Graduate School of Design, which awarded him the Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design in 2000.

In 2005, as part of the Accelerated Growth Programme, Rio de Janeiro called on Jáuregui to do an urban study of Manguinhos, an area of the city with around 10 favelas. Besides a high crime rate, the area lacked public space and community facilities. Jáuregui’s solution entailed elevating the rail line along Manguinhos’s main road, allowing a park to be created below it. Completed in 2010, the park removed a physical and psychological barrier between Manguinhos and the rest of the city.

What is unique about favelas, compared to, for instance, Africa’s shantytowns and India’s slums?

What distinguishes the favelas of Rio de Janeiro is the physical continuity of the constructions with the formal city. This means that it is necessary to elaborate the connections and passages between these two dimensions of the socio-spatial configuration of the city in urbanist and architectonic ways. The constructions of the favelas are also compact and concentrated. It is different from Africa where, although I only know Africa through films and studies, I have an idea of a big sprawl, a dispersion of constructions with low density. Different too from India, which I know through doing a project in Mumbai, where there are very contrasted constructions, with the middle-class buildings inserted in the middle of slums without any connection between them, neither social nor physical. Mumbai is a really broken city and society in my opinion.

It is said that already 90% of Brazil is living in cities – far ahead of the rest of the world. What has this meant for the social fabric of Brazil and the cityscape in particular?

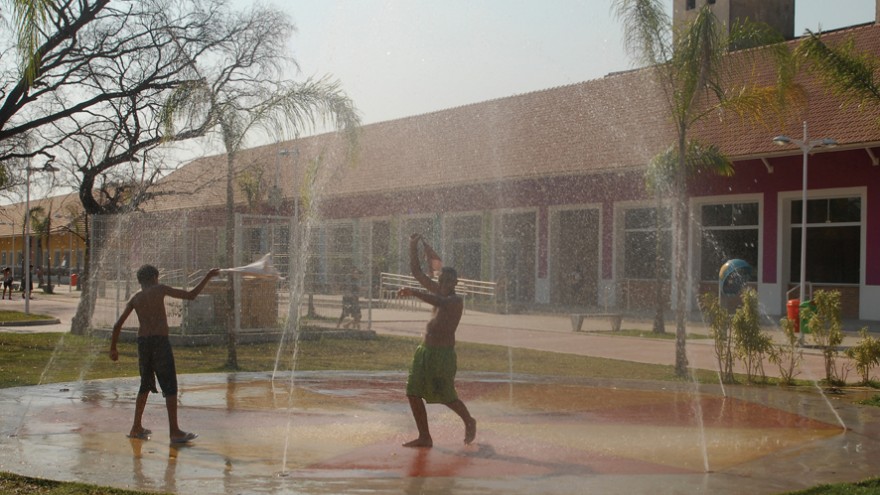

Yes, this urbanised condition of Brazil, and Rio in particular, implies a specific cityscape of mixed landscape and constructions, where favelas and the formal city appear in continuity. From my point of view, this makes it necessary to formalise this relation, modelling public space that edifies three special programmes to provoke this connection. These three programmes entail devices and spaces for the generation of work and income, sporting facilities and spaces for leisure. These three programmes – work, sport and leisure – are the three fundamental connections between the favelas and the rest of the city.

For instance, samba schools are one of the most significant connections between the poor and the middle-class, between the informal and the formal city. The school itself is also surrounded by many ancillary spaces, activities and connection points, and also conducive to the creation of conditions for the generation of culture. This is important, not only to create connections, but to empower and to inspire better living conditions

What is your attitude towards informal architecture? Should it be formalised?

It is necessary to provoke the articulation between the two intelligences: The popular intelligence that is there, in place: and the institutional intelligence of public power, which urban design carries. It’s not about formalising but about allowing connections that introduce conditions of urban and architectural quality, without destroying the existing power and richness of social life. This condition needs to be interpreted by reading the structure of the place, in parallel with listening to the demands, to form the basis of the socio-spatial urban reconfiguration.

You seem particularly interested in creating public spaces in favelas. Why are formalised public spaces so important?

Public spaces do not exist in favelas. They need to be created, conceived as socio-spatial articulators of connections between different people. But they have to be alive, full of life, 24-hours a day, because then they also improve safety. This continuity can only be assured if the exact relation between uses and spaces is captured. Public spaces are the expression of a social life and for this reason merit all our attention and design capacity.

Another on-going theme in your work is ecological integration?

The first ecological principle is using the existing. First and foremost in terms of human resources and secondly with materialistic means, above all acknowledging the effort already made (both physically and economically) to build from what’s already there. Because of this, my approach to projects is based on reading the existing structure of the place and in listening to the demand, before incorporating other social and environmental disciplines later (such as environmental impact, ground characteristics, water, air quality and contamination studies).

I agree with Deleuze and Guattari that there are three ecologies: Mental, social and environmental. First the decontamination of preconceptions, without which one cannot think at all; second the revision of the set of social ties; and third what is relative to sustainability. Also one has to add Thierry Paquot’s concept of “existential ecology” that implies the revision of all behaviours both individual and collective in relation to the environment.

Integrating ecological concepts into the work, sport and leisure edification programme demands an attentive examination of the natural and social context of the intervention. The reuse of the historical wisdom about resources to handle heat, light, ventilation or acoustic isolation, without needing excessive technology, is also tightly related to the economy of energy.

Why are so many of your buildings brightly coloured?

The use of colour in architecture is a way to incorporate the building into its context. For the Aztecs “colour is the thing of Gods”, meaning something very important. On the other hand, the use of colour in popular culture is associated with the idea of beauty. People who have money and have already resolved their “interior life”, which is the organisation of their privacy, paint their facade using colours that recall where they are from.

You seem to work closely with the government, which is an enviable position. How did you establish that relationship?

Usually through public competitions for projects, and sometimes through direct or personal invitations from the public authorities because of the exposure that my work has received.

You seem very committed to and passionate about your work, even prepared to discuss it on a Sunday?

What is good is always made with passion, in love as in work…