Octopi, invented by engineers Hongquan Li and Manu Prakash, is a low-cost automated imaging platform that can detect parasites and bacteria in people by scanning bodily fluids at a rate of 1 million cells per minute.

The creators of Octopi recognised that medical professionals in remote areas, especially in areas with high malaria and TB rates, were struggling to process medical samples and diagnose patients quickly enough.

Medical facilities in these areas are often without sufficient supplies and sometimes even without electricity. Prakash, leader of Stanford University’s Prakash Labs, wanted to create something that solved the problem of processing blood samples faster and therefore diagnose and treat patients quicker.

On Prakash Labs’ Twitter account, Prakash documents the thought processes behind the creation of Octopi: “In 2015 [on a] trip to Uganda, I realised that we need low cost but high-throughput and flexible tools to fight these deadly diseases. Tools need to adapt to the context (large hospital or small village) - like ‘transformers’.”

Later that year, Prakash’s first inspiration for the automated imaging platform came to him in the form of DVD drives.

To increase their understanding of scanning processes and autofocus imaging, the team collected hundreds of DVD players, broke them down, took them apart and reverse engineered them.

It was at this point that Li joined the project to built the Octopi from scratch.

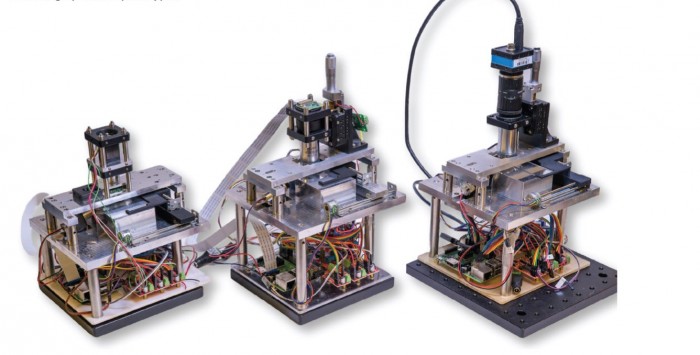

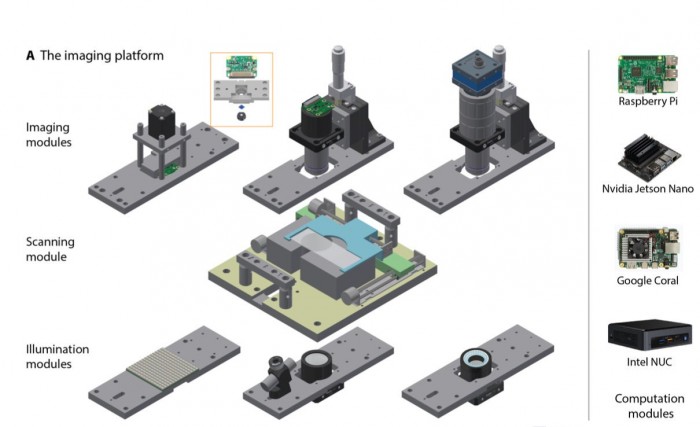

The modular, stackable design of Octopi allows medical practitioners to swap out modules depending on the type of parasite or bacteria that they are trying to track. And in order to reduce imaging and identification time in medical facilities, the Octopi is fitted with a scanning and autofocus module with a flatness of almost 300nm.

The Octopi resembles a sort of deconstructed microscope platform. It is made up of circuit board, image scanner and microscopic lens and is connected to a computer that displays the scanned imagery.

According to Prakash, the Octopi can scan between 1.5 to 5 million cells/minute, using bright field and fluorescence in order to create gigapixel images.

With the development of this tool, Prakash wants others to go out there and develop simple tools to solve problems that plague the world.

He believes that the microscopic world is for everyone: “I imagine a future where a network of low-cost automated ’smart’ microscopes capable of identifying pathogens arm community health workers - and work hand in hand. It’s possible through collective efforts from a community of research, developers, clinicians and philanthropy.”

The project was sponsored by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, NSF Biology and the Gates Foundation. The team is currently in the process of deploying 100 Octopi to medical professionals and facilities in the field.

Read more:

Rapid Assessment of Malaria (RAM) detects malaria in 5 seconds

Ugandan designers create a bloodless, reusable malaria test kit