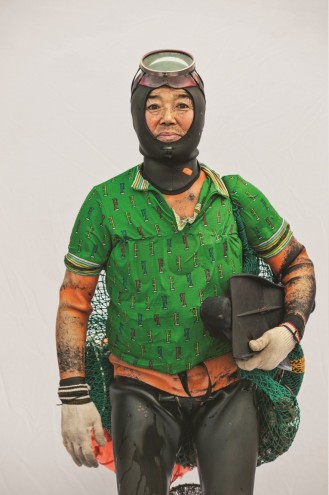

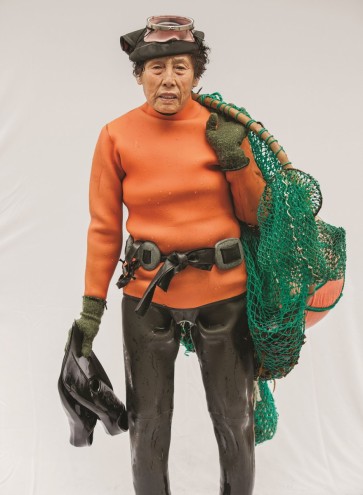

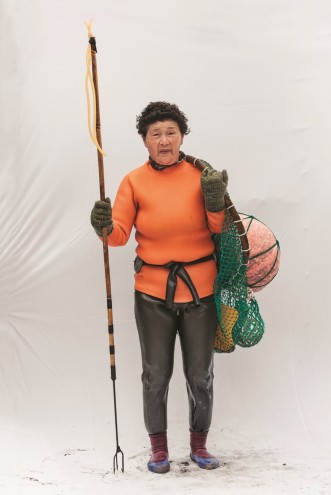

For hundreds of years, women of the South Korean island province of Jeju have made their living trawling the ocean's floors for seafood to support their families. Known as haenyeo (or sea women), these free divers are representative of the semi-matriarchal family structure that has endured in the region. Between 2012 and 2014, photographer Hyung S. Kim captured images of the haenyeo as they emerged from the seas, creating a series of stunning portraits that depicts them in their element.

First tasked with offshore diving during the 17th century while most men of the province were occupied with fishing or rowing war boats out at sea, by the 18th century they significantly outnumbered male divers. Without the use of an air tank, these women descend to depths as deep as ten metres for two minutes – often with lead weights strapped to their waists ensuring a faster descent, leaving only a tewak (floatation device) floating above the surface.

In front of a plain white backdrop, Kim convinced the haenyeo he would spot emerging from the waters to allow him to take their picture. Though not used to being photographed, they obliged. The youngest woman he photographed was 38-years old while the oldest was over ninety. The portrait series depicts what could very well be the last generation of haenyeo.

Like many traditional cultures throughout the years, the number of haenyeo women has decreased, and the main concern for the elder community is that this decline could lead to the vanishing of a matriarchal culture that has long dominated the island. As of 2014, only about 4,500 haenyeo women – most upwards of 60-years old – were still active. In 2014, South Korea applied to have the haenyeo placed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

“For me, the photos of the haenyeo reflect and overlap with the images I have of my mother and grandmother,” Kim told the New Yorker. “They are shown exactly as they are, tired and breathless. But, at the same time, they embody incredible mental and physical stamina, as the work itself is so dangerous; every day they cross the fine line between life and death. I wanted to capture this extreme duality of the women: their utmost strength combined with human fragility.”