First Published in

“Some people believe that football is a matter of life and death. I am very disappointed with that attitude, it is much, much more important than that,” Bill Shankly, one of Britain’s most respected football managers, famously said.

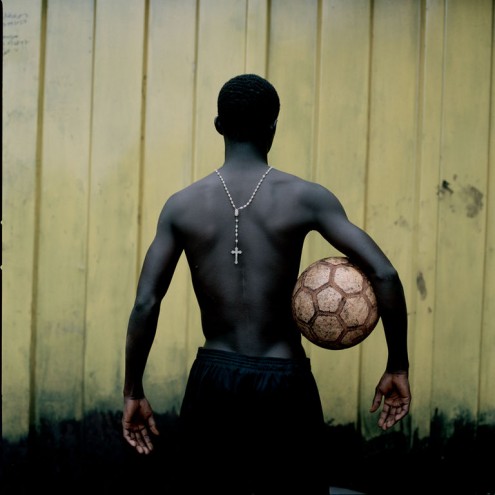

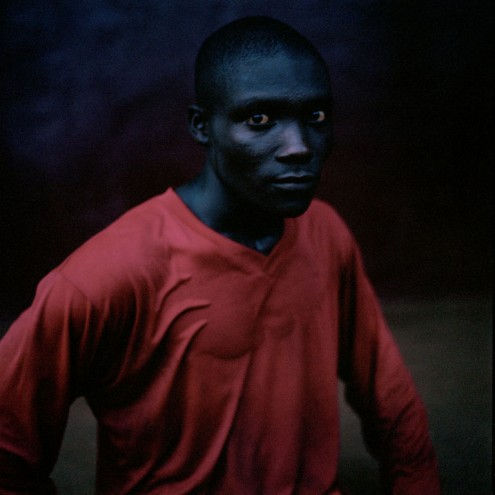

For some soccer is just a game, a time for friends to come together and kick a ball around. There are those who make it a career, training daily and travelling the world to compete for the title of number one. But soccer, for Africans, has all the makings of a religion without actually being one. Whether it’s called soccer or football, these devotees live to play the game

“Football in Africa, I don’t know if many people realise, is almost like a religion. To an extent, it’s like a survival mechanism,” confirms photographer Jessica Hilltout with her latest exhibition and book, Amen. Showing her journey of discovery through the so-called “dark continent”, the title speaks of the spiritual realm of the game. Meaning “so be it”, “amen” was the word most used by the people she worked with and came to know so personally, always greeting her with: “Amen, may this project work and may people see our passion for football.”

Born in Belgium, it was Hilltout’s nomadic exposure to the world that sparked her fascination with images. She attended Art College in Blackpool, England, worked in advertising and finally found herself travelling through Central Asia and Africa photographing the seemingly unimportant. This led to Faces and Places and The Beauty of Imperfection, exhibitions highlighting the imperfections surrounding people and finding beauty in the peculiar. Now, as South Africa prepares to welcome the world, she is back in Africa hoping to show that soccer is bigger than a television screen.

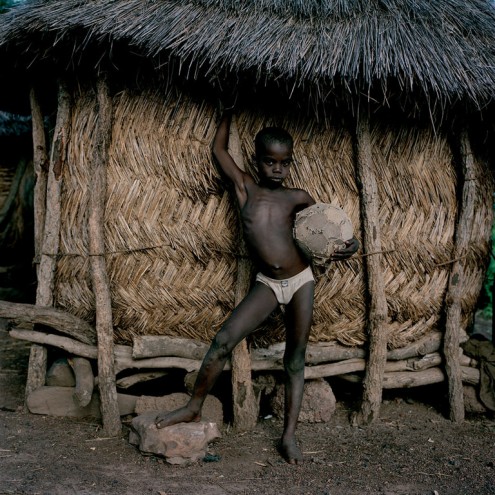

Hilltout travelled through South Africa, Mozambique, Malawi, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Madagascar, exploring rural communities and discovering how villagers seemingly plan their days, if not their lives, around training and matches to be played. “I met people in one village who walked two days to play a match in another village… and not to play professionally, but just for pleasure,” she describes, as she points out pictures in her rustic and overflowing diary that traces her expedition.

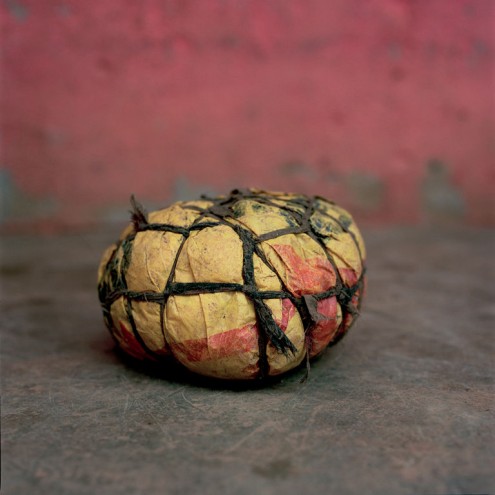

In the same way that the soccer culture reflects the people’s love of the sport, the soccer balls Hilltout came across in each village reflect not only their unwavering dedication, but also the dire conditions in which many live. Made from an array of materials there are two conflicting emotions attached to the balls, according to Hilltout, when looking at her solemn photographs: “One is an emotion of sadness and the other an emotion of incredible strength.” These are not just soccer balls – what has gone into creating them and what they have endured has made them unusual, yet powerful, symbols of the aspirations permeating the continent.

A personal truth lives in each photograph. Whether it is of a boy in his underwear holding a soccer ball or the boots of a player, Hilltout seeks to capture a moment of authenticity beyond the game. In time, she plans to go back to the villages with more equipment, giving these communities the facilities to continue with this proud tradition. As for her photographs, in the shadow of the FIFA World Cup, she has shown Africans as the unsung heroes of soccer.

Amen shows in Cape Town at the João Ferreira Gallery from 9 June to 24 July, in Johannesburg at the Resolution Gallery from 5 June to 31 July, and in Brussels from 10 June to 18 July at Le Botanique. Website: www.jessicahilltout.com/amen.